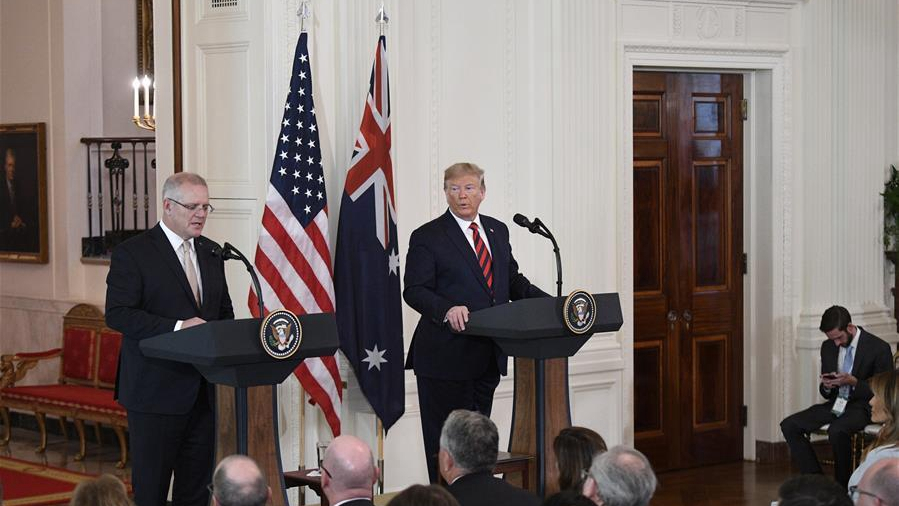

U.S. President Donald Trump attends a joint press conference with visiting Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison at the White House in Washington D.C., the United States, September 20, 2019. /Xinhua

**Editor's note: **Iram Khan is a Pakistan-based commentator on international and commercial affairs. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

For the second time in a year, Australia has found itself embroiled in U.S. President Donald Trump's election campaign and the politics that surround it. Last September, Trump had sought Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison's help in discrediting the Mueller investigation into foreign interference in the 2016 U.S. election.

Now he is expecting Morrison to sell his conspiracy theory that the COVID-19 causing coronavirus originated in a laboratory in China. Fortunately, Morrison has refused. On Friday, he flatly declared that he had no evidence to suggest this presumption on the virus's origin.

The refusal may have come partly due to Trump's unwillingness to describe the evidence he has supposedly seen to make up this theory. And it speaks of growing discontent among U.S. partners about Trump's inconsistent accusations.

This mixed messaging policy is a major source of American isolation in international affairs. The more world leaders want to support the U.S., the more Trump takes unilateral decisions to embarrass them.

While it is difficult for his staff members to defend him, global leaders allied with the U.S. are finding themselves in a tighter spot, as they are answerable to their own people as well. When Trump says that the virus will one day disappear like a miracle or injecting disinfectants will treat COVID-19, his officials and his backers have no option but to look the other way.

During this health emergency, it is important to take the opinion of medical professionals over that of politicians. Experts in reputed publications are repeating time and again that the novel coronavirus most likely has its origins in wildlife. Even the report from the U.S. intelligence community, stating in clear terms that the virus was not man-made and was not genetically modified, could not convince Trump.

That's probably because 2020 is an election year, and the Republicans turning how well they can blame their failures on China into a test. The blame game is reaching new heights since a party memo urging anti-China rhetoric surfaced.

Republicans' inability to defend Trump comes from the fact that the president accuses the media of spreading fake news but pedals absurd claims himself. This is an indication that the U.S. might have entered a post-truth era where perceptions matter more than reality. And who else can be better suited to distort perceptions than the president?

One of his predecessors is attributed to have said, "you cannot fool all the people all the time." Now that the Australian prime minister appears to be calling the bluff, Trump might be losing the confidence of another ally.

U.S. President Donald Trump attends a COVID-19 press conference at the White House in Washington, D.C., March 9, 2020. /Xinhua

Morrison considers the U.S. responsible for most of the COVID-19 cases in Australia. Back in March, while rejecting the idea that China had done anything deliberately, he pointed the finger at the U.S. by stressing that the spread in his country was "a function of the number of people who travel between the U.S. and Australia."

After rising internal pressure about his initial inaction and continued mishandling of the crisis, rebukes from his foreign allies are going to further weaken his position in his re-election bid. Trumpis at odds with the EU over trade and climate change and with East Asian countries over a bloated U.S. military presence.

Australia's dissension will be a further blow to Trump's radical approach to diplomacy, wherein both his adversaries and friends are at the receiving end of his "maximum pressure" tactic. This wangle has brought him much harm as he found himself impeached after trying to compel Ukraine for digging up dirt on presidential candidate Joe Biden.

Likewise, the possibility of pressurizing Morrison on the coronavirus issue cannot be ruled out. When seeking his assistance against the Mueller investigation in September, Trump was accused of bypassing the "Five Eyes" intelligence-sharing network and personally reaching out to him for political gain.

Simon Jackman, head of the U.S. Studies Center at the University of Sydney, was at that time of the viewthat there was a probability of a threat involving trade. Australia has an exemption on steel and aluminum tariffs from the U.S., and anything that could risk this privilege would have cost Morrison direly. So, in the most likelihood, it was an instance of Trump coercing an ally for his domestic political ends.

The Australian prime minister has to walk a fine balance between bowing to Trump and heedingthe opinion of his own public. According to the U.S. Studies Center last year, fewer than one in five Australians wanted to see Trump re-elected.

Whereas, polls by Sydney's Lowy Institute revealed that two-thirds of Australians believed Trump had weakened the relationship between the two countries. The polls also suggested that a third of Australians wanted their country distanced from the U.S. under Trump.

Meanwhile, China remains Australia's largest export partner. Its exports to China are more than a third of its total exports, and experts believe its fortunes are linked to China's economy, not to that of the U.S.

This makes a case for Australia to re-orientate its foreign relations in light of its trade interests and how the U.S. treats it diplomatically. Instead of becoming a party to the polarized politics of the upcoming U.S. presidential election, it should take up international issues objectively and listen to health experts when it comes to the coronavirus.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at [email protected].)

简体中文

简体中文