04:43

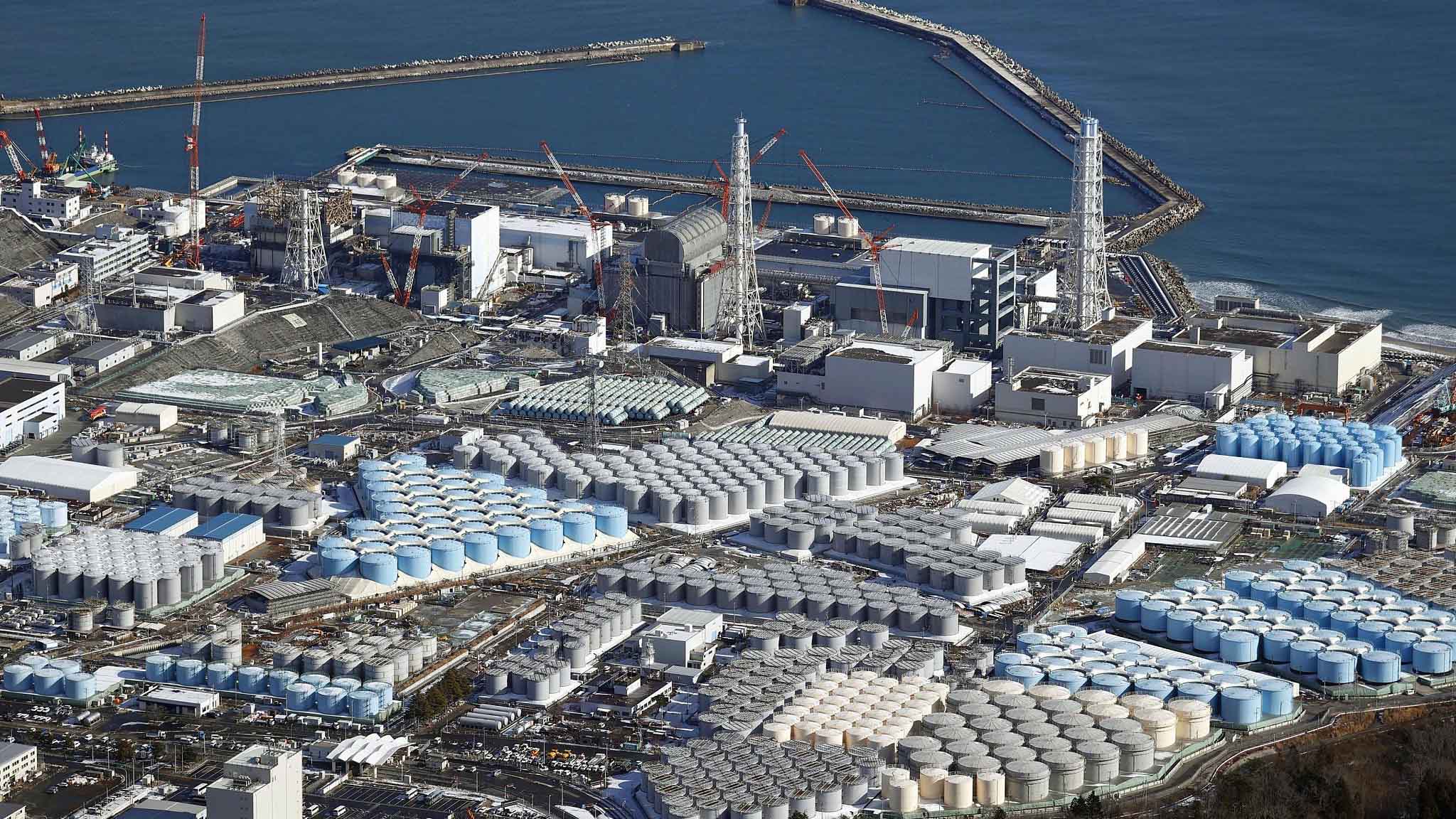

Japan's recent decision to dump over 1 million tonnes of contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean has reportedly caused a new wave of concern and disturbance around the globe. The wastewater is from the Fukushima plant, the site of a nuclear disaster almost a decade ago.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) backed the Japanese government's plan to dispose of the water, saying the plan meets the global standard of practice in the nuclear industry, and releasing wastewater from nuclear power plants is commonplace. However, the local fishery industry, residents and international environmental organizations have slammed the decision.

There's been an ongoing discussion on the potential aftermath of the release of the contaminated wastewater. But it's impossible to be sure about the potential risks and long-term consequences of releasing such a large amount of radioactive waste into the ocean.

Here are some key facts to mull over before the official announcement is released in the coming days.

1. What is nuclear wastewater?

Nuclear wastewater is the water collected from the cooling pipes used to cool the reactors when the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant was crippled in 2011.

For now, the water remains contained in around 1,000 tanks at the former nuclear power station.

2. Why do they want to release the wastewater?

According to the New Scientist, the amount of water in the tanks is still increasing due to rainfall and groundwater flowing into the site. IAEA estimated the existing capacity would be full by mid-2022.

3. What's in the wastewater, and is it harmful?

The water has been filtered to remove over 62 radioactive contaminants, said New Scientist. The main radionuclide remaining in the water is tritium, which is difficult to separate from water because it's a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, part of the water molecules itself.

The Tokyo Electric Power Company, which runs the plant, had tried to find a way to filter the tritium but failed because most contemporary technology can't work when tritium is in low concentrations. Francis Livens, a radiochemistry professor at the University of Manchester, said releasing tritium is a common practice among most operating nuclear sites elsewhere in the world.

"Tritium is the least radioactive and least harmful of all radioactive elements," said James Conca who is specialized on geologic disposal of nuclear waste in a Forbes article. Tritium is only harmful to humans in very large quantities.

4. What are Japan's options?

Last April, IAEA sent a team to review the contaminated water. It gave two "technically feasible" options. They can release the water into the sea or evaporate it into the air.

The IAEA said both options were used by operating nuclear plants.

Conca said, "Putting this water into the ocean is, without doubt, the best way to get rid of it. Concentrating it and containerizing it actually causes more of a potential hazard to people and the environment. And is very very expensive with no benefit."

The other option is to build more tanks to store the water on land or underground. It will take close to 60 years for the tritium to lose most of its radioactivity. However, the cost of storing the hazardous water and the risk of leakage must be considered, according to Ken Buesseler, a marine radiochemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution said.

"[Discharging it into the sea] is probably the sensible option because anything else causes bigger problems," said Livens.

**5. What are the consequences of the release? **

There has been controversial debate on the consequences of discharging the water into the sea.

Buesseler said the impact on marine life and humans consuming seafood is unknown unless a better understanding of the radionuclides in the tanks can be achieved.

However, Pascal Bailly du Bois at the Cherbourg-Octeville Radioecology Laboratory in France has a more positive attitude toward the issue. He said, "The radiological impact on fisheries and marine life will be very small, similar to when the Fukushima reactors were operating under normal conditions.”

According to Kyodo News, Japan's fishery industry and some local governments strongly oppose the proposal out of concern that consumers would shun seafood caught nearby. The fishery business in Japan has long been affected. There are 15 countries and regions still restricting Japanese agricultural and fishery products due to the nuclear crisis.

6. What are the measures to take on such plan?

Although the risk is low according to many experts, it is still advised that close monitoring and abiding by scientific advice will be crucial, according to Simon Boxall, a principal teaching fellow in ocean and earth science at the University of Southampton.

"It's questionable to rush into such decision based on the study made by Tokyo Electric Power Company, which has lost the global credibility and trust," Ma Jun, director of Institute of Public and Environment Affairs, told CGTN.He called for transparency and confrontation with the company among neighboring countries.

简体中文

简体中文