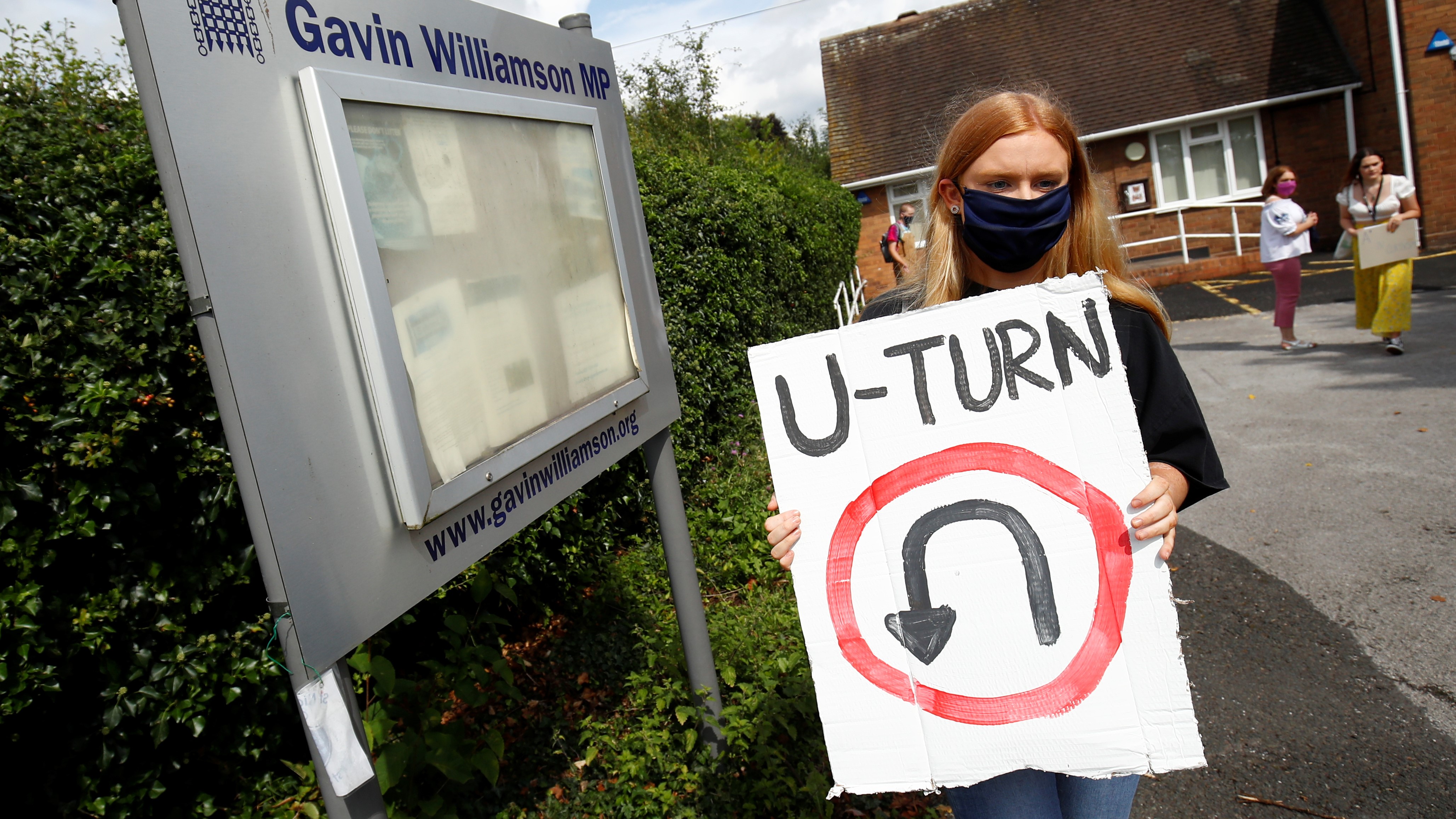

There had been calls for the government to go against their own algorithm, something which the government has now listened to/Reuters

The UK government has been forced into an uncomfortable and public U-turn on how grades are being allocated to school pupils in England who were unable to sit exams because of the COVID-19 lockdown.

A-levels, the national end-of-school exams that crucially decide the academic and professional future of typically 18-year-old students, didn't happen this year.

Instead, the government produced a system that started with the teachers' predicted grades for each student and then "standardised" them by using the past performance of their particular school or academy.

As a result, students from traditionally high-performing schools were buoyed up, while students from larger under-performing schools tended to be marked down.

About 40 percent of A-level results in England were, in the end, downgraded – in some cases turning predicted A grades into D or even E grades, depending on how the algorithm rated the school and the number of pupils in it.

There was supposed to be an appeals process but, amid the many stories of apparent injustice, it was modified and then withdrawn over the weekend.

Headteachers had already called on universities to adjust expectations for this year's new school applicants and at least three colleges at Oxford University said they would go on the teacher-predicted grades rather than the algorithm-adjusted ones.

Now, the government has ruled that the grades will be given using teacher assessments and the computer results are forgotten.

The second set of summer exams in England, GCSEs, typically taken at age 16, are due to come out on Thursday and they too will follow the teachers' recommendations rather than the algorithm.

Thousands of teenagers and their parents will breathe a sigh of relief, but they've been through days of turmoil only to end up back at square one.

It's a decision that had already been made in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, but Westminster has appeared slower to make its decision, with even some MPs from Johnson's own Conservative Party calling the situation a "shambles."

简体中文

简体中文