Not long after noon on Feb. 6, President Donald Trump strode into the elegant East Room of the White House. The night before, his impeachment trial had ended with acquittal in the Republican-controlled Senate. It was time to gloat and settle scores.

“It was evil,” Trump said of the attempt to end his presidency. “It was corrupt. It was dirty cops. It was leakers and liars.”

It was also soon forgotten. On Feb. 6, in California, a 57-year-old woman was found dead in her home of natural causes then unknown. When her autopsy report came out, officials said her death had been the first from COVID-19 in the U.S.

The “invisible enemy” was on the move. And civil unrest over racial injustice would soon claw at the country. If that were not enough, there came a fresh round of angst over Russia, and America would ask whether Trump had the backs of troops targeted by bounty hunters in Afghanistan.

For Trump, the virus has been the most persistent of those problems. But he has not even tried to make a common health crisis the subject of national common ground and serious purpose. He has refused to wear a mask, setting off a culture war in the process as his followers took their cues from him.

Instead he spoke about preening with a mask when the cameras were off: “I had a mask on,” he said this past week. “I sort of liked the way I looked ... like the Lone Ranger.”

These are times of pain, mass death, fear and deprivation and the Trump show may be losing its allure, exposing the empty space once filled by the empathy and seriousness of presidents leading in a crisis.

Bluster isn’t beating the virus; belligerence isn’t calming a restive nation.

Angry and scornful at every turn, Trump used the totems of Mount Rushmore as his backdrop to play on the country’s racial divisions, denouncing the “bad, evil people” behind protests for racial justice. He then made a steamy Fourth of July salute to America on the White House South Lawn his platform to assail “the radical left, the anarchists, the agitators, the looters,” and, for good measure, people with “absolutely no clue.”

“If he could change, he would,” said Cal Jillson, a presidential scholar at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “It’s not helping him now. It’s just nonstop. It is habitual and incurable. He is who he is.”

Over three and a half years Trump exhausted much of the country, while exhilarating some of it, with his constant brawls, invented realities, outlier ways and pop-up dramas of his own making. Into summer, one could wonder whether Trump had finally exhausted even himself.

Vainglorious always, Trump recently let down that front long enough to ponder the possibility that he could lose in November, not from the fabricated voting shenanigans he likes to warn about but simply because the country may not want him after all of this.

“Some people don’t love me,” he allowed.

“Maybe.”

VICTORY LAP

On Feb. 5 in the White House residence, Trump had watched all the Republican senators, save Mitt Romney of Utah, dutifully vote to acquit, ending the third impeachment trial in U.S. history.

His rambling, angry, 62-minute remarks the next day were meant to air out grievances and unofficially launch Trump’s reelection bid — with the crucible of impeachment behind him, his so-so approval ratings unharmed, Republicans unified and the economy roaring.

The president’s advisers also watched, relieved that the shadow of impeachment — which loomed first due to Russia’s U.S. election interference, then his Ukraine machinations — was now behind them, letting them focus on the reelection battle ahead.

The plan was taking shape: a post-trial barnstorming tour, rallies meant to compete with the Democratic primaries and a chance for the president to dive into the reelection fight that had animated so many of his decisions thus far in his term, according to some of the 10 current and former administration and campaign officials who requested anonymity to speak candidly for this story.

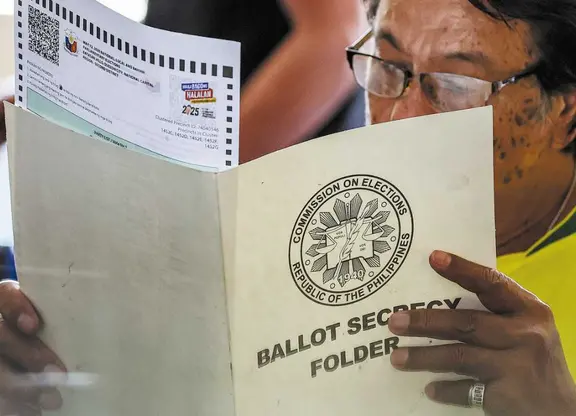

A few days earlier, the first coronavirus death outside China had been recorded, in the Philippines. Known cases of the disease in the U.S. were under a dozen. The U.S. had declared a public health emergency and restricted travel to and from China. But this was not something Trump wanted to talk about in the glow of acquittal and fog of grievance, and events had not yet forced his hand.

The day was meant to mark a new chapter in Trump’s presidency. It did. But not the one the president and his people expected.

THE LONGEST DAY

Trump’s whirlwind trip to India was meant to be a celebration and in some ways was. He addressed a rally crowd of 100,000 and visited the Taj Mahal.

But in a quick talk to business people at the U.S. ambassador’s residence, he felt compelled to address the virus, which had begun rattling the foundation for his argument for another four years in office: the economy.

Fighting jet lag and anxiety about a dive in the stock market, Trump was up much of the previous night on the phone with advisers, peppering them with questions about the potential economic fallout of the outbreak, according to the officials who spoke with The Associated Press.

“We lost almost 1,000 points yesterday on the market, and that’s something,” Trump told the two dozen or so business leaders. “Things like that happen where — and you have it in your business all the time — it had nothing to do with you; it’s an outside source that nobody would have ever predicted.”

The virus was “a problem that’s going to go away,” he said. “Our country is under control.”

But the markets fell again the next day, creating their biggest two-day slide in four years. When Trump boarded Air Force One well after sundown in India, he was in a rage about the virus and his inability to slow the market tumble with reassuring words, according to the officials.

Trump barely slept on the plane as it hurtled back to Washington overnight, landing early in the morning Feb. 26 after more than a dozen hours in the air, creating the effect of one endless day. He then quickly tore into aides about Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, who had publicly predicted that the virus’ impact would be severe.

It was already too late to pretend otherwise, not that Trump stopped trying. Warning signs had been missed. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention failed in an early attempt at a coronavirus test. Trump had refused to turn up the pressure on China for fear of alienating Xi Jinping and scuttling a trade deal.

His conventional weapons failed him. The virus doesn’t have a Twitter account.

“Trump was elected to burn down the system and entertain,” said Eric Dezenhall, a crisis-management consultant who has followed Trump’s business, TV and political careers.

“When things get terrible, people don’t want a leader to burn down the system and entertain. We actually want a system. And you can’t bully a disease, which has been his one maneuver for 74 years.”

The president returned to the West Wing to watch the market fall yet again and told aides that, later that day, he would take the podium and preside over the coronavirus task force briefing for the first time. This would become a daily ritual for Trump to try to force his belief that the virus was under control even as infections surged and the death toll mounted.

The virus was not the only exterior event shaping his week. Three days later, Joe Biden began his remarkable political comeback by trouncing Bernie Sanders in the South Carolina Democratic primary.

Trump’s assumption that he would be running on the back of a strong economy against a socialist had been flipped on its head.

Coronavirus cases were about to soar.

(AP)

简体中文

简体中文