02:05

In the newly released proposal for China's 14th Five-Year Plan, innovation has been placed at the core of the country's continued modernization. Ability is a key component of innovation, especially when it comes to scientific research.

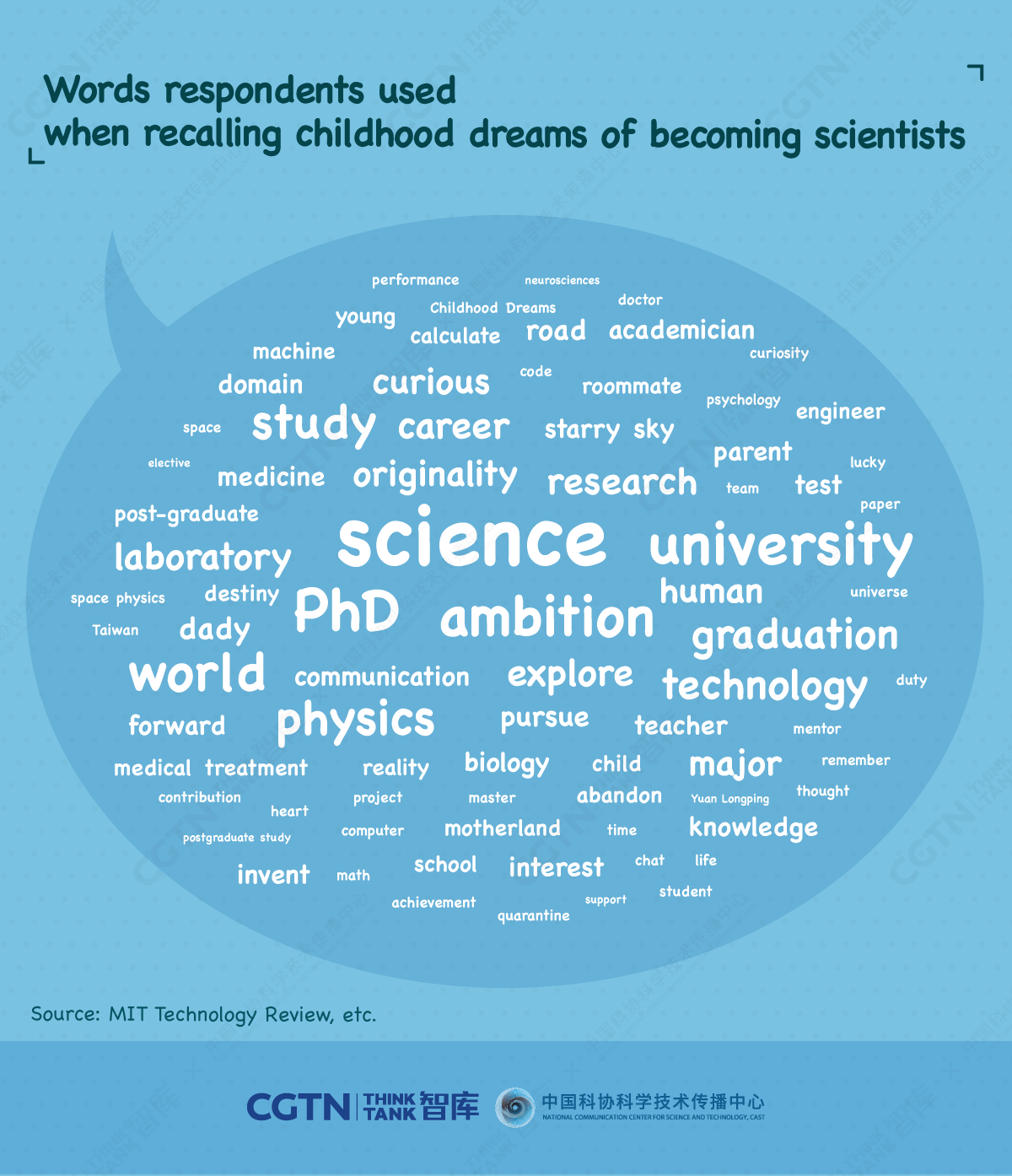

Interestingly, many Chinese have dreamed of contributing to scientific research, especially those born in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s.

Lots of Chinese Dreamed of Becoming Scientists during Childhood

The comments of 61 Chinese citizens who wanted to be scientists as children, most of whom are now in their 30s, were compiled in a variety of publications, including the MIT Technology Review. Many used similar words and phrases to describe these early dreams.

These keywords illustrate their life paths up to this point, but what made these children dream of being scientists in the first place?

At first, they may not have fully understood the way science benefits humanity. Perhaps as children they thought scientists were remarkable people who could do anything. As they grew older, the heroic aura that had attracted them faded, and they realized their goal was not to become scientists, but rather to continue to question, explore and innovate.

Dr. Zhong Nanshan, one of China's most famous pulmonologists, once said that "if we present scientists as role models, it will help young people to learn to express their ideas, and to ask 'why,' more often."

The dream of being a scientist comes from the general reverence for science in Chinese society. Science here is never just for scientists, and those who dream of becoming scientists since their childhood are in many ways the epitome of the Chinese admiration of science.

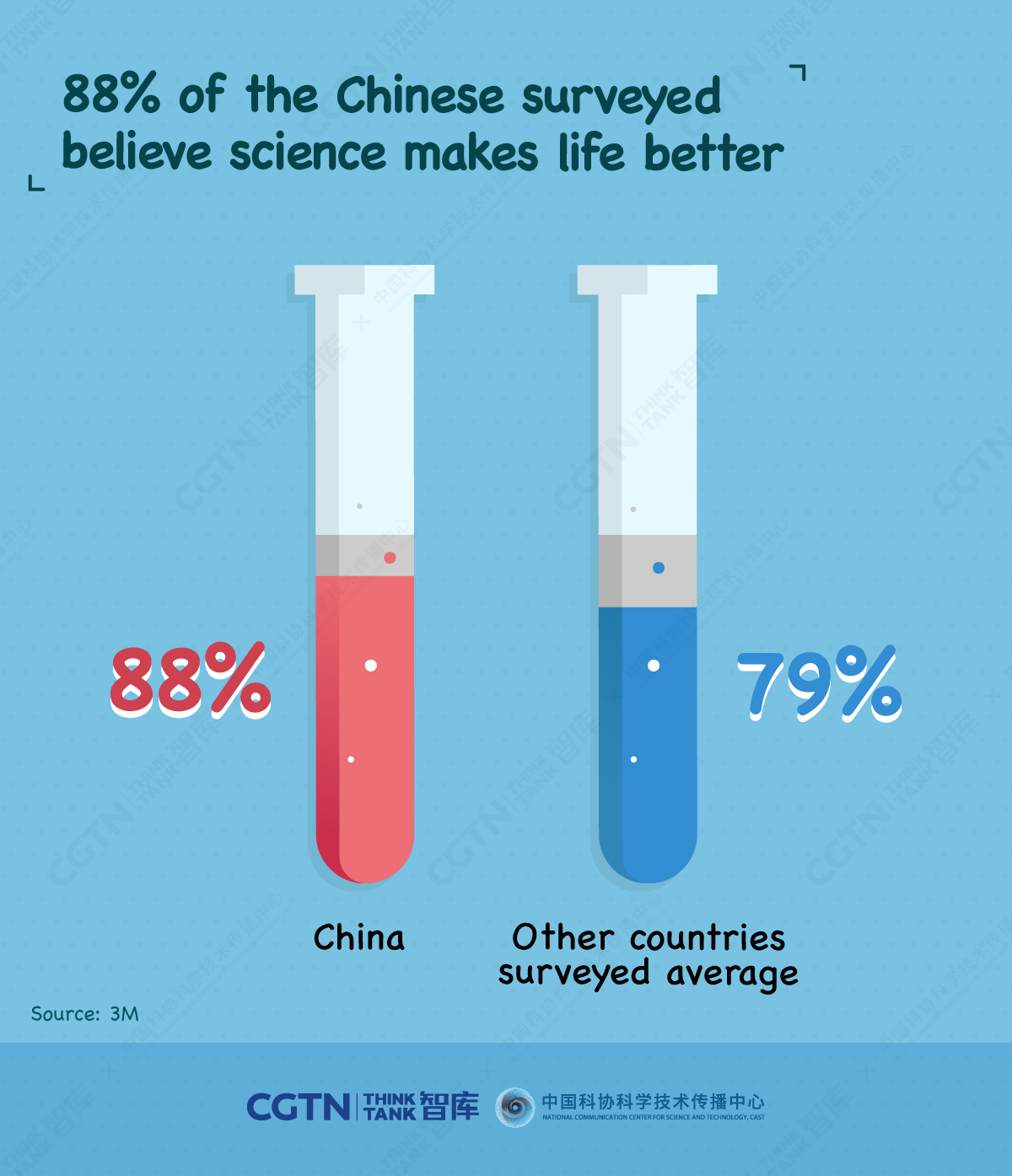

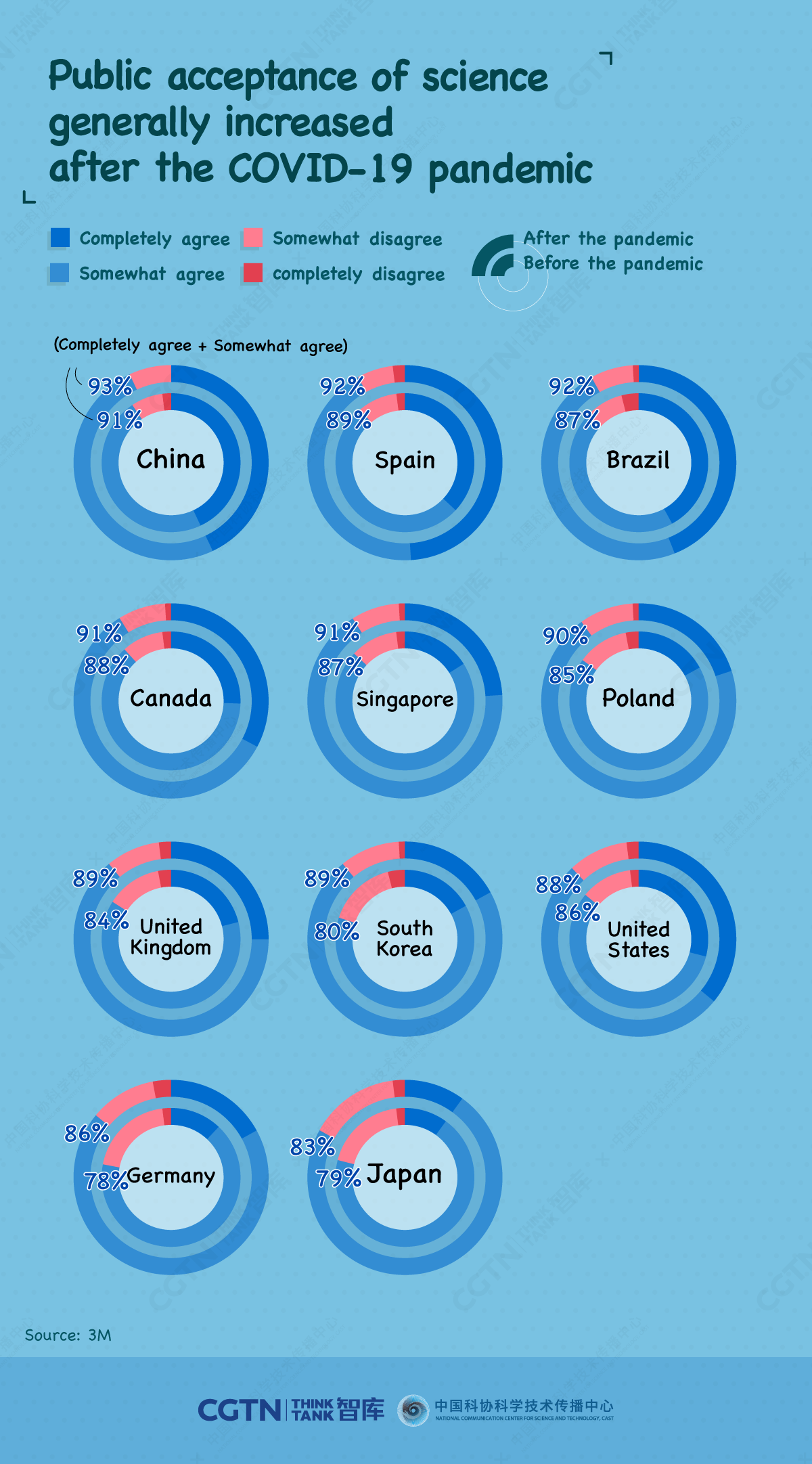

In 2020, 3M, the U.S. technology and manufacturing company, conducted a survey on attitudes towards science in more than 10 countries. They found that 88 percent of Chinese believe that science will make their lives better, 9 percentage points higher than the average level in other countries surveyed.

Behind the Chinese Science Dream: Revolutionising Daily Life

This belief stems from the revolutionary changes to people's lives wrought by the technologies derived from science.

Xiang Biao, a professor of Social Anthropology at Oxford University – born in 1972 in Wenzhou, east China's Zhejiang Province – once recalled that "in 1984, we bought an electric fan, which was the second electrical device my family owned. It could generate cool air and turn itself around. The pleasure that brought in the summer transformed our lives."

It isn't always easy to empathize with personal experiences, but data helps make change more intuitive. In the early days of the People's Republic of China, the rice yield was only 1,890 kg per hectare and there was an urgent need to increase production.

While doing some of the first field tests at the Anjiang Agricultural School in Hunan Province, Yuan Longping, then a young teacher, discovered a natural hybrid rice, with an excellent shape and large ears, capable of producing more than 160 grains, far exceeding the yield of the ordinary rice species farmers took at that time.

From that point onward, he researched hybrid rice, continuously seeking to improve its yield. In 2017, the super hybrid rice variety "Xiang Liangyou 900 (Chaoyou 1000)" selected by Yuan's team produced an average yield of 17,235.3 kg per hectare, setting the world record for the highest yield, nine times higher than 68 years ago.

In 2020, the double-season hybrid rice yield per hectare exceeded 22,500 kg, and China's per capita grain production exceeds 470 kg, higher than the internationally recognized safety limit of 400 kg. Hybrid rice accounts for about 50 percent of the 30 million hectares of rice planted in China.

Disease is the natural enemy of mankind. Trachoma, a chronic infectious inflammation of the cornea, caused by Chlamydia Trachomatis, was the leading cause of blindness in China before the 1950s. At the time, China saw a 50 percent rate of trachoma prevalence, and in some rural areas, the rate was as high as 90 percent. Finding the cause of the disease was therefore vital.

After a series of experiments, Tang Feifan, one of China's first-generation medical virologists and microbiologists, disproved the trachoma's bacterial etiology, and successfully isolated Chlamydia Trachomatis. Risking blindness, he conducted experiments on himself to double-check his findings, which eventually led to a major change in the classification of microorganisms, added an additional order of Chlamydia and reducing the incidence of trachoma from nearly 95 percent to 10 percent, promoting the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of trachoma.

Similarly, Tang's work helped China eradicate smallpox, a virulent infectious disease that plagued humanity for at least 3,000 years, and which claimed the lives of 300 million people in the 20th century. Using the ether sterilization method he developed, the production of pox seedlings was increased, allowing China to eradicate smallpox in 1961, 16 years before it was finally eradicated worldwide.

Public Acceptance of Science Generally Increased After the COVID-19 Pandemic

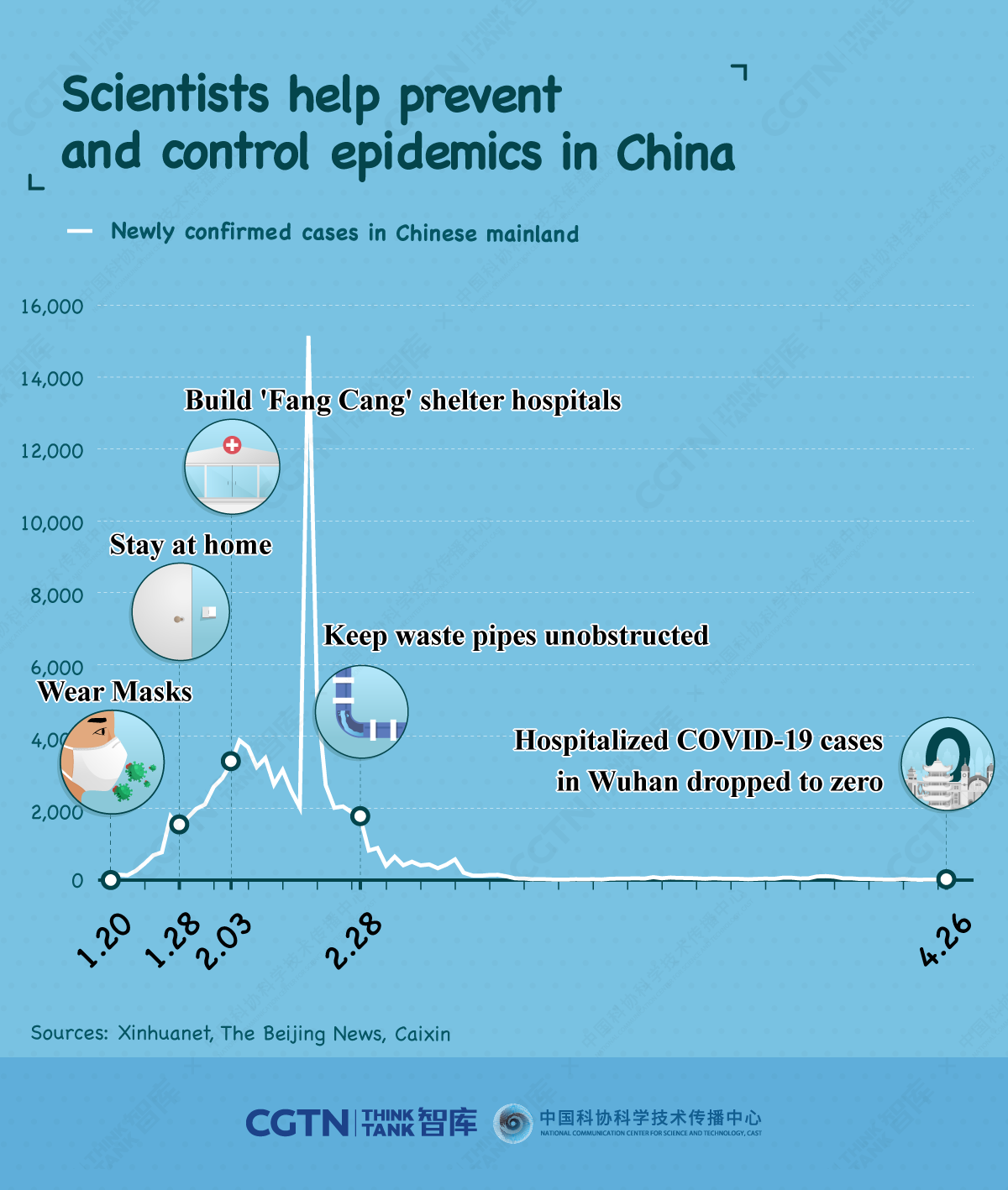

It is because of scientists that science can benefit the public. Scientific guidance, as well as a long-standing trust in science, has helped China prevent and control pandemics efficiently.

The COVID-19 pandemic not only validated the importance of science, but also increased public recognition of science worldwide.

From mid-2019, and mid-2020 – in other words, before and amid the pandemic –3M conducted a survey into the public attitudes towards science. They found a general rise in acceptance of the expression "I trust science"(somewhat agree + completely agree), with 9 percentage points more Koreans and Germans agreeing with the statement in 2020 than in 2019.

Science is Not Just for Scientists

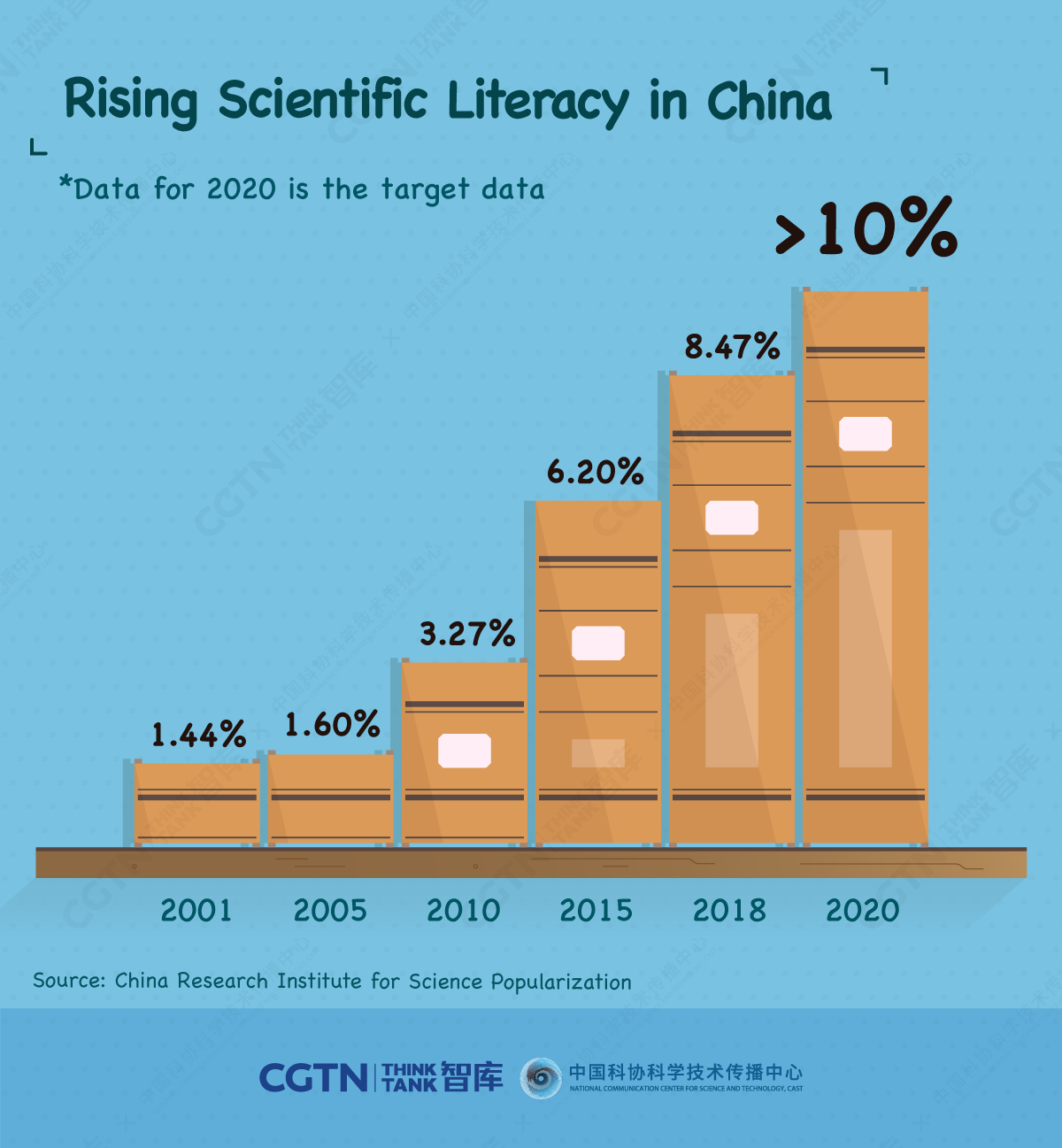

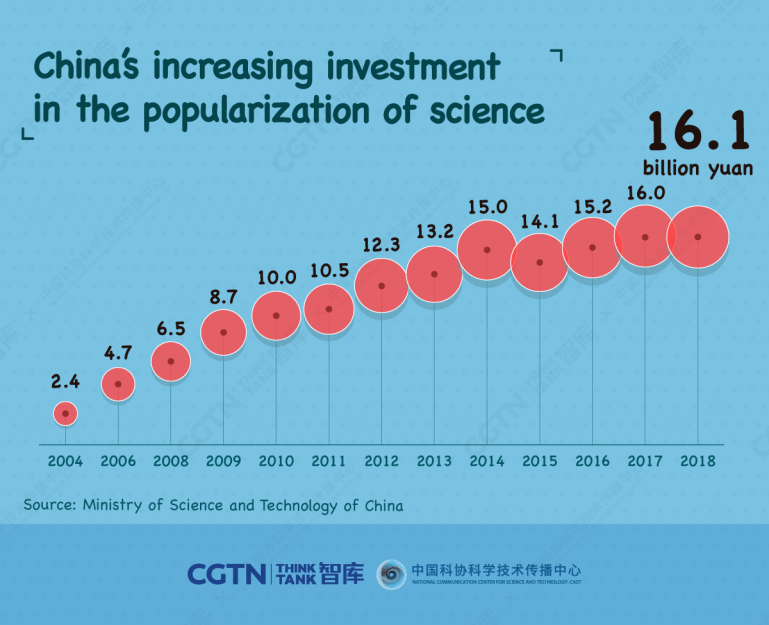

It's worth noting that the high recognition of science in China is related to increasing public scientific literacy. China is also setting national goals to ensure this increase continues. Under the 13th Five-Year Plan, by 2020, the level of public scientific literacy was due to exceed 10 percent. The proposal for the 14th Five-Year Plan includes promoting science and craftsmanship, increasing the popularity of science as a subject, and creating a national atmosphere that advocates innovation.

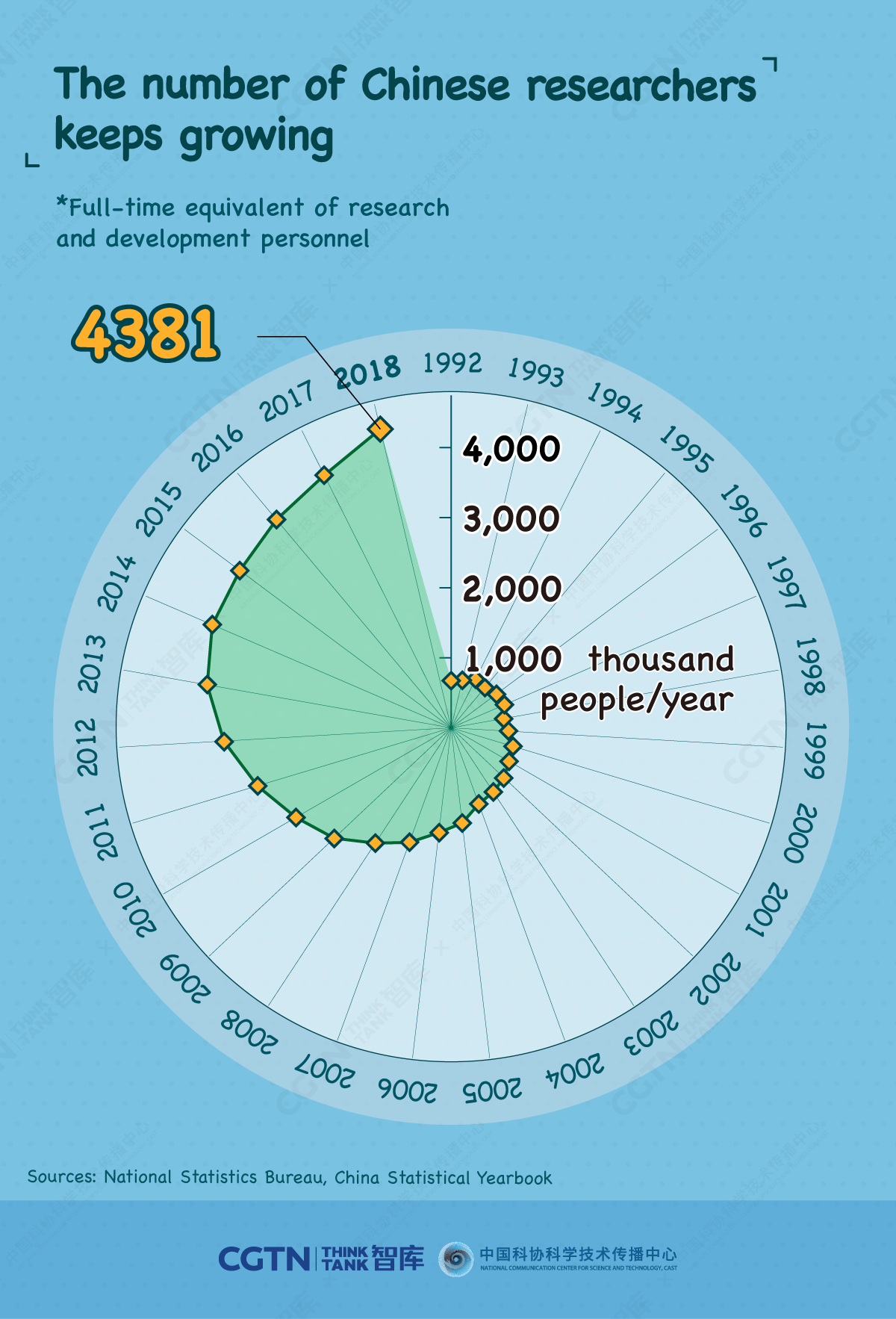

At the same time, a growing number of people are choosing careers in research, to follow their own dreams of becoming scientists.

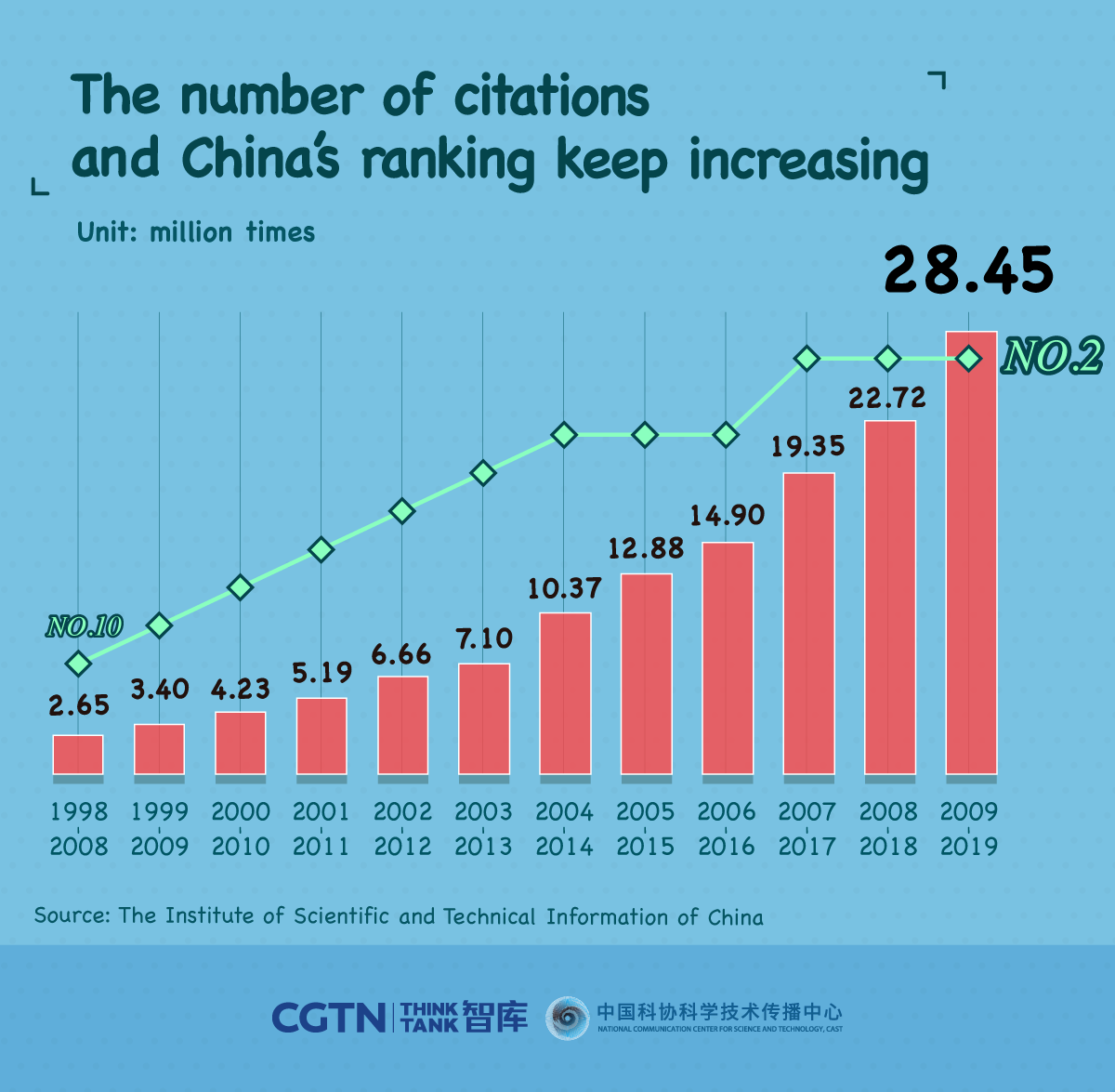

As research expands, citations of Chinese researchers are continuing to rise. According to statistics from the Institute of Scientific and Technical Information of China, as of October 2019, Chinese scientists had been cited a total of 28,452,300 times between 2009 and 2019, an increase of 25.2 percent from a time period between 2008 to October 2018. Since 2007, China has ranked second in the world in terms of citations.

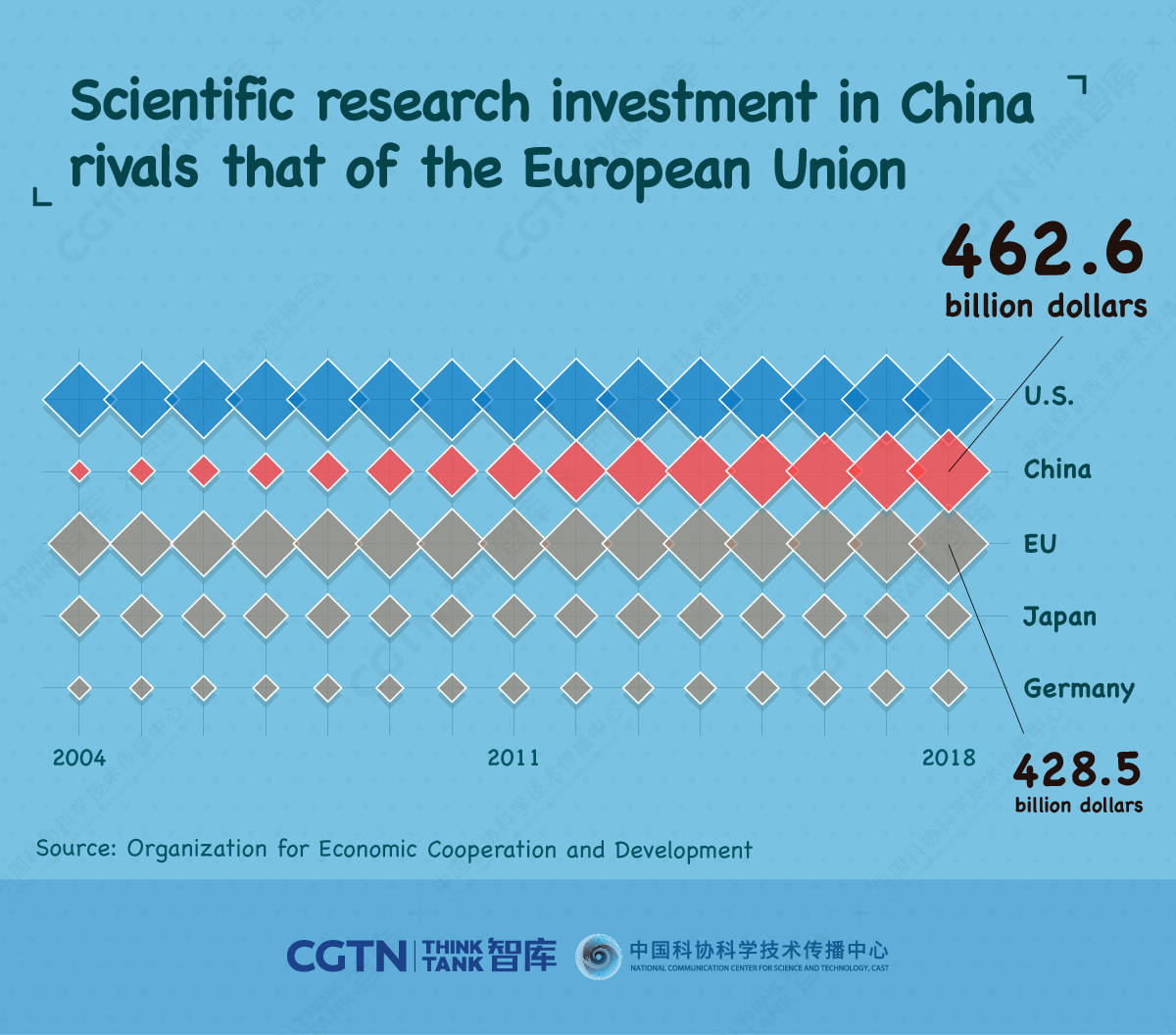

Of course, all of this is inseparable from the investment in popularizing science and scientific research, which has been increasing year by year. In 2019, China invested 2.17 trillion yuan, 2.19 percent of its GDP in RD, which was roughly on par with the EU average.

Perhaps not all the children who dreamed of becoming scientists grew up to become scientists. But such a thing isn't that important. Science is not just for scientists. It is related to the survival and growth of mankind, and so it has touched the lives of everyone. So perhaps a child did not grow up to become a scientist, but he or she continued to advocate science, and that is important, in itself.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at

.)

简体中文

简体中文