Tectonic activity has been detected on the moon by researchers who have discovered a system of moving ridges topped with boulders on its near side.

"There's this assumption that the moon is long dead, but we keep finding that that's not the case," said Professor Peter Schultz at Rhode Island's Brown University.

"It appears that the moon may still be creaking and cracking - potentially in the present day - and we can see the evidence on these ridges," explained Professor Schultz who co-authored a study published in the journal Geology.

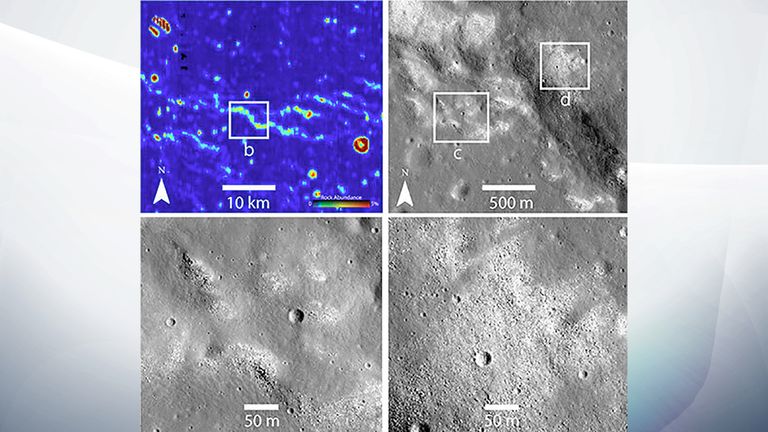

Image:The strange bare spots suggest an active tectonic process. Pic: NASA

The majority of the moon's surface is covered by something called regolith, the powdery dust of rocks created by constant meteorite impacts.

Because the moon has no atmosphere to speak of, rocks and orbiting debris crash right into its surface and blow apart.

There are very few spaces on the lunar surface which aren't covered by regolith - but some seemingly new spots have recently been discovered.

Image:Regolith is powdery dust covering the moon's surface

Adomas Valantinas, a graduate student at the University of Bern who was a visiting scholar at Brown, used data gathered by NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) to spot these strange bare spots.

"Exposed blocks on the surface have a relatively short lifetime because the regolith buildup is happening constantly," Mr Schultz said.

"So when we see them, there needs to be some explanation for how and why they were exposed in certain locations."

"Just as concrete-covered cities on Earth retain more heat than the countryside, exposed bedrock and blocky surfaces on the moon stays warmer through the lunar night than regolith-covered surfaces," the researchers said.

So using a tool on the LRO to measure the surface's temperature, Mr Valantinas was able to discover more than 500 patches of exposed bedrock on narrow ridges following a pattern across the nearside of the moon.

Such ridges had been discovered before, but they were on the edges of very ancient lava-filled impact basins and could be explained by continued sagging in response to weight caused by the lava fill.

The new study found that these ridges are actually related to a mysterious system of tectonic features - ridges and faults - unrelated to the lava-filled basins.

"The distribution that we found here begs for a different explanation," Professor Schultz said.

Apollo 11: Eleven things you didn't know about the moon landings

Mapping out all of these exposed ridges, Mr Valantinas and Prof Schultz discovered an interesting correlation between them and a previous NASA mission.

Back in 2014, NASA's GRAIL mission discovered a network of ancient cracks in the moon's crust, which became channels for magma from the moon's core to flow to the surface.

This network lined up almost perfectly with the blocky ridges.

"It's almost a one-to-one correlation," Prof Schultz said. "That makes us think that what we're seeing is an ongoing process driven by things happening in the moon's interior."

So the ridges, according to these scientists, are ancient magma flows which are still heaving upwards - breaking the surface and draining the regolith into cracks and voids, leaving the blocks exposed.

"Because bare spots on the moon get covered over fairly quickly, this cracking must be quite recent, possibly even ongoing today," they say.

Moon is shrinking 'like a raisin' and shaking, says NASA

But what is causing this? According to the scientists, the tectonic movements may actually have begun billions of years ago with a giant impact on the far side of the moon.

Professor Schultz had previously proposed such an impact had formed the 1500-mile South Pole Aitken Basin, and shattered the interior on the opposite side of the moon - the side facing the Earth.

Magma from the core then filled these cracks and controlled the pattern detected in the GRAIL mission. The blocky ridges comprising this network now trace the continuing adjustments along these ancient weaknesses.

"This looks like the ridges responded to something that happened 4.3 billion years ago," Prof Schultz said. "Giant impacts have long lasting effects.

"The moon has a long memory. What we're seeing on the surface today is testimony to its long memory and secrets it still holds."

简体中文

简体中文