Many international K-pop fans are eager to fully understand what their favorite stars are saying but not all of them can afford to learn the Korean language.

For them, Kang Woo-sung, a young Korean-American in New York, recently published an English dictionary on some of the most frequently used vocabulary in Korean pop music, TV shows and films.

Kang said he had been voluntarily translating and writing about Korean pop culture on many relevant information-sharing Websites to feed global fans' curiosities since 2008 and found out that certain questions are repetitive and common.

"In particular, many international viewers asked questions about the nuance or other subtle meanings of K-pop-related words that the direct English subtitle could not sufficiently fill in for," he said during an interview with Yonhap News Agency in Seoul on Friday.

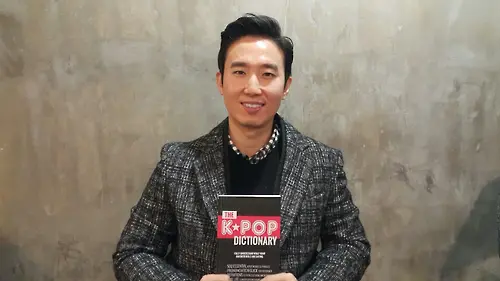

Kang Woo-sung, author of "The K-pop Dictionary," poses after his interview with Yonhap News Agency in eastern Seoul on Dec. 2, 2016. Photo: Yonhap

That's how he decided to make a "dictionary" of K-pop related vocabularies, the first and only dictionary of its kind.

"The K-pop Dictionary," lists some 500 essential vocabulary words and colloquial phrases that are frequently used by young South Koreans.

"This book is not meant to be a bestseller, but a steady-seller for those who are willing to know about Korean culture," Kang said. "I hope the book will broaden the cultural exchange of Korea and other countries around the world."

Kang is in the process of writing his next book about the Korean pop culture, slated to be rolled out in 2017.

Kang's book, about the size of an adult hand, is full of amusing slang such as "bal yeongi (foot acting)," meaning sloppy acting, and "ganji," meaning a cool, stylish vibe in fashion.

Some of the words in the book are so new that even native South Korean adults fail to give exact translations of the words. Some apparently originated from English words, but used with slightly different connotations. "Butter face," for instance, means "a woman whose face undermines her great body" in the U.S., while in Korea, the word simply means "an ugly-looking woman."

Some words coined by non-Korean K-pop fans, like "bias" and "bias ruiner," even have become unique terminology. The word, which is not used among Korean fans, means "favorite idol" and "someone who has the potential of becoming one's new idol."

Kang Woo-sung, the author of "The K-pop Dictionary," speaks during an interview with Yonhap News Agency in eastern Seoul on Dec. 2, 2016. Photo: Yonhap

Kang authored the book to raise the popularity of Korean pop culture, or hallyu, on a global scale by providing what global consumers of K-pop want to know and learn. Likewise, those who learn Korean will find the language more intriguing, he said.

As the son of a Korean immigrant to the United States, the 34-year-old graduated from Denver University in Colorado and earned his master's degree in consumer psychology in New York University. Since then, he has traveled back and forth and worked in both countries numerous times.

In New York, he engaged himself in national branding as a member of the Cyber Advisory Member at The National Unification Advisory Council under South Korea's Lee Myung-bak administration. The task was to get national branding to operate in a broader sense, encompassing K-pop as well as Korean culture, history and traditional heritage.

As the key boosters of hallyu, Kang picked two factors: mutual understanding among different cultures and candid reviews of homegrown cultural content.

To Kang, the gap between K-pop seen at home and overseas seems to have broadened over the years, due to the magnifying nature of the media industry.

"The media has a tendency to focus on starting phenomena and bringing it to spotlight. In Korean media's case, I think, they focus on things with national pride because they sell," he said.

The cover of "The K-pop Dictionary" by Kang Woo-sung. Photo: Yonhap

"It is true that such move can over-glorify (the global K-pop) and mislead Korean people into believing that K-pop is sweeping the globe. However, I think the move is not completely groundless in its roots, because the move is growing among the young generations of the non-Korean communities. National pride is important, but enhancing (Korean) content should start from an accurate understanding of where we are."

Kang confided that K-pop is, in fact, a growing movement in many countries, since it is advocated by the young generation. To him, K-pop is not a minor cult in the U.S. anymore, especially since it has steady listeners and is known in many small towns.

By public awareness in average American people, Kang estimated that the awareness of K-pop falls short to Japanese "anime," or animated films, but surpasses J-pop, or Japanese pop music.

"It is quite inspiring that K-pop has a growing number of young international fans, in terms of consumer psychology. Younger generations are more open to alien cultures and willing to share what they like. Once they grow fond of K-pop culture, their penchant is likely to last as they grow up," he said.

(Yonhap)

简体中文

简体中文