Two years have passed since the European Union Court of Justice recognized an individual's "right to be forgotten," leading to the removal of delicate personal information found through Internet search engines.

Google Inc., which operates the largest search engine, has established a structure in Europe to deal with requests for information removal.

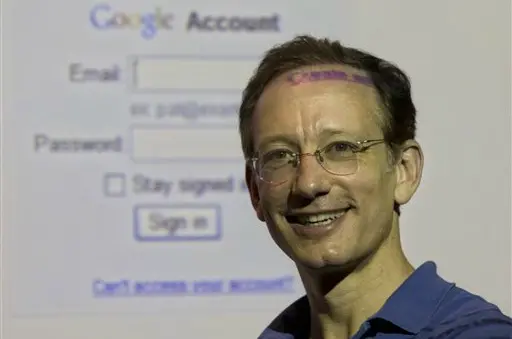

In an exclusive interview with The Asahi Shimbun, Peter Fleischer, Google's global privacy counsel, was asked about such issues as the various factors that have emerged over the past two years as well as the outlook for the right to be forgotten in the future.

**Question: **The European Union Court of Justice issued its ruling on the right to be forgotten in May 2014. What has occurred since then?

Fleischer: The right to be forgotten was a new right that had not existed before. We received over 1.5 million (requests) in just about every category since this process began across all of Europe.

For Google, that's a lot of requests to analyze because every one of these requests has to be looked at almost as a court would look at these issues.

**Q: **What were the most common types of requests?

**A: **A lot of the requests relate to people's professional lives. For example, doctors or dentists who might have been accused or convicted of malpractice in the past want to have that removed.

Businesses that might have been accused of fraud in the past want to have those elements removed. An art dealer who had been convicted of trading forgeries wanted to have that removed. Government officials want to have their prior political views removed if they've changed their political views. Government officials who in their youth belonged to radical parties now want the histories of their past removed.

One example I found very interesting was a pianist who was giving a public concert. A newspaper review was positive, but not positive enough for the pianist, who wanted it removed. A painter asked us to remove all references to exhibitions that he'd done earlier in his career because he changed the style in which he paints.

Q: What criteria do you use in deciding whether or not to delete information?

**A: **Our fundamental thinking is the removal should be the exception and should only occur when there is a legitimate reason.

We have to balance the right of privacy against the public's right to access the information.

Regarding search results for individuals who have committed crimes, some of the things we have to look at are time factors, such as how long ago did it occur, whether it was a minor crime or not and whether it was a crime with a high public interest.

If it is not a public figure and it is a minor issue and there is not much public interest in it, we would probably remove it.

We get every so often requests from victims of crimes and those are usually removed.

If something relates just to someone's personal life or family matters, if things relate to minors or children, then we have a much stronger preference to remove the content.

Q: What are some of the other factors that you take into consideration?

**A: **Whether something is relevant to a person's profession is important. That would be the example of criticisms of a doctor or a dentist that are relevant to his or her professional practice which may be of interest to other people who want to research and find a good doctor or a dentist.

We also have a strong preference to leave up information that is political speech. To the extent that it is political speech in one way or another, there is more public interest in continuing to access it even if the person has changed their mind.

We have to look at every case, case by case, fact by fact.

In the case of the pianist, we did not remove the review. We thought they were just going to have to deal with an average review.

A mayor of a European city convicted of corruption came to us just before running for re-election, asking for all the references to that to be removed. But we did not delete the information.

**Q: **What is the background and experience of those people who are making the decisions?

**A: **After the EU Court of Justice decision, we have a group of people who speak every one of the 20-something languages in Europe to be able to make a determination.

They do the initial review of the cases. If there is a very standard case that falls within the guidelines, they have the authority to make the decision.

If the balance is unclear or if it's the first time that we've seen a case like that, then they'll escalate it to more senior reviews.

We have a committee that I sit on which meets once a week where we talk about the most difficult cases of the week.

We are not a court and the parties are not in front of us, so we can't ask them questions. We just have to rely on what they told us.

Q: What was your most difficult case?

A: A German who was a minor had gone to the United States and was convicted of sex with a minor. That was a crime in the United States, and it was published in the newspaper with his name.

In Germany, had it been the same crime, his name would not have been published. He was seeking removal of this because he was saying, "This is ruining my life."

There was also a question of publishing the person's name.

I'm not going to say what the decision was because it would violate the privacy of the person.

**Q: **Don't you also have difficult cases that require you to consider the veracity of the original information as well as the context in which that information was transmitted before deciding whether to remove it?

**A: **Our teams are not a court that gets to have a deposition of the witnesses, but they do research.

**Q: **There is also criticism about having Google, a private company, making decisions to delete search results that may be in the public interest. What is your view about that?

**A: **We're making these decisions in Europe because the court ordered us to make the decisions in Europe. We're trying to play the role conscientiously, but if we had not been ordered to play this role we would never have volunteered to do it.

We are making decisions about other people's content, these are not decisions about Google's own content. That is awkward for us.

Q: But isn't that your social responsibility as the largest search engine because we would be unable to find the contents in the world of the Internet without a search engine?

A: My point is to ask the question, "Who in society should make the decision?"

The best placed to make decisions are courts.

We're doing it because we were told to do it. We have criteria and guidelines, and we make the decision. This balancing act is difficult, and we only have partial information when we do it.

Earlier, we were talking about someone's public figure status. How are we supposed to know that someone is a public figure? The person may very well be a public figure in their community in Finland or in Portugal and it may be obvious to everyone in Finland or Portugal that they are, but it's not obvious to us.

Q: Has it been a burden to make decisions on such a large number of removal requests?

**A: **The important question is not whether this is a burden for Google.

Europe struck the balance one way. We have to be prepared as a global company to have different processes.

Google is a large company. I think the harder question is to say, "How would smaller companies handle their obligations?"

Q: There have been cases in Japan of courts being asked to remove search results. In such cases, the right to not be interfered with in the rehabilitation of individuals who may have committed a crime in the past has been used as a criteria for making a decision. Does Google believe that the right to be forgotten does exist?

A: This is an issue that has been widely discussed, including in Europe.

Our position is to conduct business according to the laws of the region where we are.

If there is a right to be forgotten in Europe, we will abide by that.

If the United States, where there is a stronger sense about the freedom of expression written into the Constitution, says there is no such right, then that is what we will follow there.

If you are asking whether the right itself should exist, my answer would be "Yes." But that is an issue concerning the original information that was transmitted.

We are a search engine so we should not be in a position to decide whether contents should be removed or not.

If The Asahi Shimbun received a request to remove an article, an internal decision could be made based on Asahi Shimbun policy.

But we are being asked to make a decision on contents of information that was transmitted by someone else.

I believe that is a very awkward situation.

Q: How do you view the French move to apply the right to be forgotten to searches anywhere in the world?

A: We will respect French law in France and Japanese law in Japan.

The French are asking us to do global removals according to French law. We think the French position is wrong, and we are appealing it to the top court in France.

Countries make one category or content illegal under their local laws. In Thailand it's illegal to criticize the king. In Turkey it's illegal to criticize the dignity of the Turkish state.

In Russia it's illegal to engage in what's called "gay propaganda."

If those countries could force global companies to remove such content worldwide, no one in the planet would be able to see anything unless it was considered acceptable by every country on the planet.

The right to be forgotten as it has been defined and implemented in Europe is imperfect. The process has evolved.

Every country around the world has to ask itself the question about the right to be forgotten and the public's right to access information.

The important question is, "Is the balance being struck correctly between privacy and the right to access information in each country under each country’s laws?"

Peter Fleischer , born in 1963, became global privacy counsel for Google Inc. in 2006 after working for Microsoft Corp.

(THE ASAHI SHIMBUN)

简体中文

简体中文