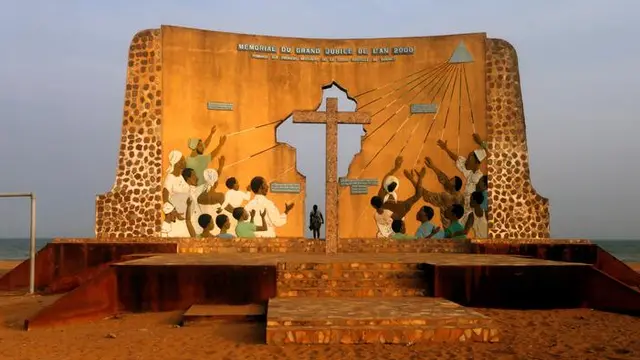

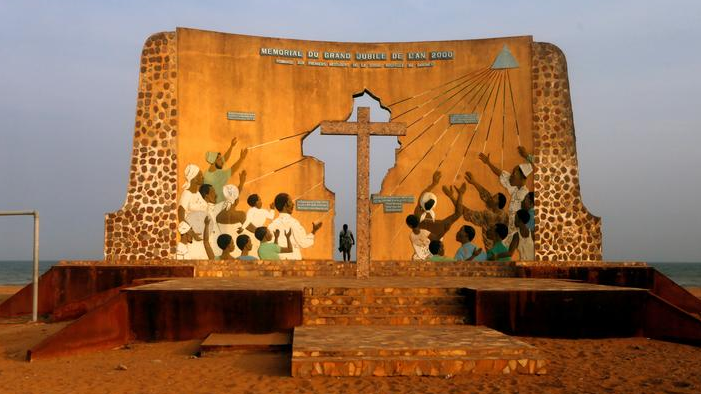

A woman stands beneath a monument commemorating the "Door of No Return" where enslaved people were loaded onto ships in the historic slave port town of Ouidah, Benin, July 18, 2019. /Reuters

"I don't want to survive. I want to live." The words said by an African American slave in the movie "12 Years a Slave," a 2013biographical film adapted from a 1853 slave memoir by Solomon Northup, tells of the harsh, fear-ridden life that many like him suffered in the American South.

In the late 18th century, the cotton industry in the southern United States saw a rapid expansionafter theinvention of the cotton gin, a machine that revolutionized the industry and enabled profitable processing of short-staple cotton. As efficiency in the production process enhanced substantially, the demand for labor on cotton plantations became much greater. Unlike today, where the industry is largely mechanized, growingand picking cotton at the time relied entirely on human labor.

With cotton becoming the most important textile supporting the manufacturing of cloth, the market potential of cotton production businesses was limitless. For plantation owners in the southern U.S. states, usingslaves was the answerto generating lucrative profits.

In the three decades following the 1790s, about 250,000 enslaved Africans were transported to the United States, nearly half of the overall number transported there. Although Congress banned the importation of slaves in 1808, it did not stop slave traders from smuggling them into the country, and plantations in the Deep South were further reinforced as the domestic market supplied them with another 1 million slaves. In 1860, there were nearly four million enslaved Black people in the U.S., accounting for 13 percent of the overall population.

"Cotton produced under slavery created a worldwide market that brought together the Old World and the New: the industrial textile mills of the Northern states and England, on the one hand, and the cotton plantations of the American South on the other,"wrote Mehrsa Baradaran, a professor at the University of California, Irvine School of Law, in a piece contributed to

The New York Times Magazine

.

Thanks to the huge fortunes they had amassed for themselves, plantation owners in the South had immense political capital at the time. Coupled with the support of a series of pro-slavery presidents, Supreme Court justices and lawmakers from Congress, they were guaranteed disproportionate political power at the federal level and were enabled to further expand their cotton businesses in the new territories they gained.

Over time, the slave market became an indispensable part of the cotton production industry, as the former played an important role in influencing the latter.

For plantations, the consistent search for labor wasnot the only key to success, exertingdraconiancontrol over enslaved labor wasthe other weapon that plantationowners needed to wield, and that control reeked of the capitalism and greed that incentivized such practices.

The success of plantations hinged largely on how owners used violence as a means to maximize productivity. For them, beating the enslaved men, women and children was a way to ensure an impressive ledger, and the unbearable physical pain afflicted on them was completely disregarded. Often seen and heard amid the whippings were anguished screams, trembling and fainting from the pain.

In the day-to-day of cotton picking, each slave was assigned a quota for the day's work. If they picked more than what was required of them, they would likely be subject to a higher quota the next day. Falling short of the target would get them beaten, and the number of lashes they received was determined by that deficit.

But that was not the only factor contributing to the frequency of violent punishment faced by the slaves. The risk of being whipped also fluctuated as cotton prices went up and down in the global market. "When the price rises in the English market, the poor slaves immediately feel the effects, for they are harder driven, and the whip is kept more constantly going," fugitive slave John Brown said following his escape.

The inextricable link between slavery and American capitalism throughout the first half of the 19th century was grim and ghastly. It was not until the Civil War that the slaves in the U.S. finally broke free from their chains. But while that dark page of history was turned over, the cloud of such inhumane practices has not yet dissipated, as greed and racism are still deeply ingrained in the American system and society.

简体中文

简体中文