Master builders of the sea construct the equivalent of a complex five-story house that protects them from predators and funnels and filters food for them, all from snot coming out of their heads.

And when a delicate mucus home gets clogged, the tadpole-looking critters, called giant larvaceans, will build a new one. Usually every day or so.

These so-called "snot palaces" could possibly help human construction if scientists manage to crack the mucus architectural code, said Kakani Katija, a bioengineer at Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in California.

Her team took a step toward solving the mystery of the snot houses and maybe someday even replicating them, according to a study in Wednesday's journal Nature.

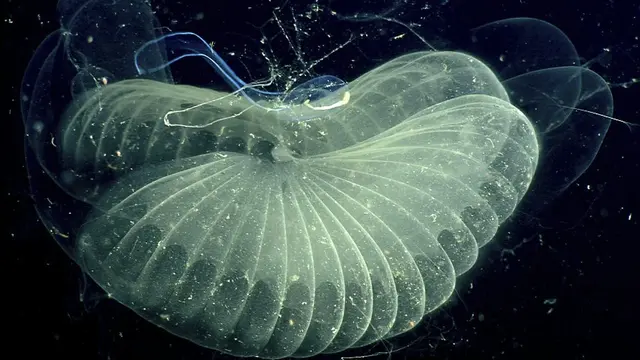

This 2002 photo provided by the Monterrey Bay Aquarium Research Institute shows a close-up view of a "giant larvacean" and its "inner house" - a mucus filter that the animal uses to collect food. /AP

The creatures inside these houses may be small, the biggest are around 4 inches (10 centimeters), but they are smart and crucial to Earth's environment. Found globally, they are the closest relatives to humans without a backbone, Katija said.

Together with their houses "they are like an alien life form, made almost entirely out of water, yet crafted with complexity and purpose," said Dalhousie University marine biologist Boris Worm, who wasn't part of the study. "They remind me of a cross between a living veil and a high tech filter pump."

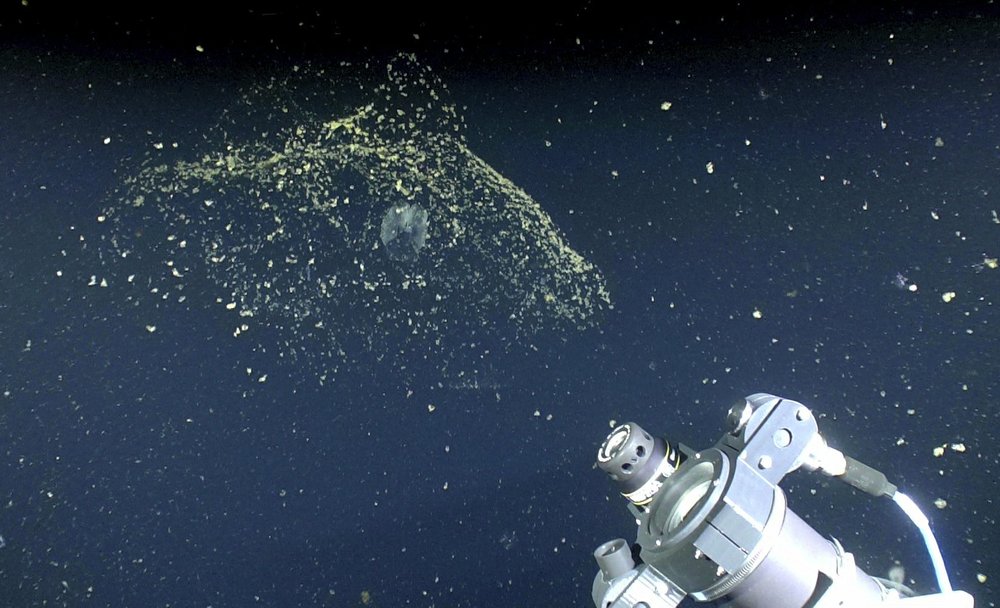

Also, when the creatures abandon their clogged homes about every day, they collectively drop millions of tons of carbon to the seafloor, where it stays, preventing further global warming, Worm said. They also take micro-plastics out of the water column and dump it on the seafloor. And if that's not enough, the other waste in their abandoned houses is eaten by dwellers of the ocean's bottom.

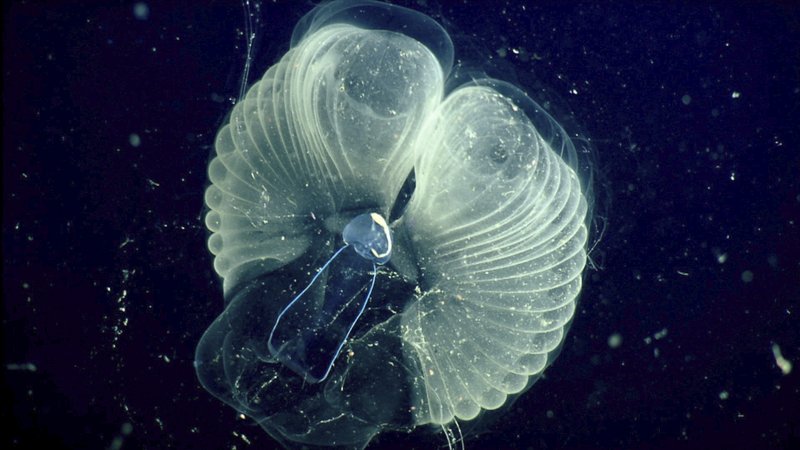

This 2015 image provided by the Monterrey Bay Aquarium Research Institute shows the inner and outer houses of a giant larvacean, left, and the laser and camera of the DeepPIV system, lower right. /AP

But it's what they build that fascinates and mystifies scientists. Because the snot houses are so delicate, researchers haven't often been able to take them to their lab. So Katija and team used a remote submarine, cameras and lasers to watch these creatures in water about 650 to 1300 feet (200 to 400 meters) deep off Monterey Bay.

These mucus structures aren't simple. They include two heart-like chambers that act as a maze for the food that drifts in, except there's only one way for it to go into the larvacean's mouth. The snot houses often are nearly transparent and flow all around the critter that looks like a tadpole.

"It could be the most kind of complex structure that an animal makes," Katija said. "It's pretty astonishing that a single animal is able to do it."

"And the houses are comparatively big, about 10 times bigger than the critters themselves, reaching more than three feet wide (one meter). It would be the equivalent of a person making a five-story house," Katija said.

"They create these small versions of houses by secreting mucus from cells on their heads and then expand those much like a balloon into the structures that we see," Katija said. All in about an hour.

In this 2015 photo provided by the Monterrey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, Kakani Katija works in the remotely operated vehicle control room on MBARI's research vessel Western Flyer as the DeepPIV system illuminates a giant larvacean. /AP

Water can flow through the structure so that when it moves through the water it doesn't give much of a motion detectable by predatory fish. That, Katija said, essentially masks the house from whatever wants to eat the larvaceans.

NASA engineers looking to build structures on the moon would probably like to learn from the larvaceans, she said.

None of this could be done in the lab. Katija's team used 3D laser scan technology to virtually fly through the inner chambers of the snot palaces, then recreated them with software to model the inner-workings of the structure. But she said scientists are still far from understanding everything going on there.

Providence College biologist Jack Costello, who wasn't part of the study, said Katija's team did "really cool work ... to detail the complex houses. It's not easy to do in the best circumstances and they've done it deep in the oceans."

"We have a lot to learn," Costello said. "I'm in awe of these animals."

(AP)

简体中文

简体中文