The first time I went to a gay club, a stranger looked over his shoulder at me and said: “Aren’t you hot in that?” It was a Thursday night at the Number One, a small underground box tucked behind a police station in Manchester, with a ludicrous corner VIP area where you would occasionally see actors from the British soap operaCoronation Street.

It was run by a chirpy, resilient fellow named Bubbles. It was 1987 and I was 16, at sixth-form college a couple of miles down the road in Rusholme. That night, I begged, borrowed and eventually stole a chunky Ralph Lauren pullover from my big brother, not thinking that in a city that frequently entertained entire dance floors of men wearing cagoules, it would be any reason for concern. In front of the bar, I flinched, said “no”(a lie) and carried on taking in every detail of this new life.

Collectively, we know the familiar mundanity of being in a workplace, on public transport, at school. We know first-hand the significant communion of attending a gig and the sanctity of being in church. When the severity of the bloodbath at Pulse in Orlando emerged, many could have imagined what clubbing on a Saturday night feels like, too. But not everyone is privy to the triumph of the neighbourhood gay disco. Maybe that’s why news bulletins about the dead and wounded, our spiritual allies, hit LGBT viewers as a personal affront, and provoked a militant anger.

The local gay disco is not supposed to be newsworthy. In the past 30 years, as the British LGBT cause has turned us from enemies to friends of the state, certain gay clubs have become enshrined in legend, turning the gay night-time experience into hallowed ground. UK gay clubs became unique mirrors to their individual political and sociological moment.

These are key moments in the fortification of the gay experience. They open us up to mainstream attention. We stop being something to be pitied, chastised, ostracised or othered and we turn into a party that everyone wants to go to. In the freedom and liberation floating through the air, there is something even to be a little envied.

You go to an unheralded place such as Pulse not to change the world, but to change your own, in incremental steps. Slowly, that feeling of being yourself fans out and becomes infectious. Slowly, word travels. Slowly, change emerges.

Because it is a minority rite of passage, the unsung gay disco is a special space, furnished with magic beyond the lighting rig and the drinks specials. It is not just about learning the real name of a drag queen or who remixed what; neither is it how to politely bat off the lad with the wandering hands and invite the one you really want to wander somewhere with. The local gay disco is the place where you stop being the odd one out. It is a halfway house, a leap towards building the home that you calls you, a little but not much different from the one you came from. A home built on love.

The gay disco has its own ecosystem, a pyramid structure that begins with the owner and waterfalls down through the DJs, security staff, the barman who will give you a free can for a smile, the promoter who chose the picture for the flyer. There is a shared vocabulary, built partly around disposition but also the raw necessity to pass on the things that school couldn’t teach you and that church refuses to.

After the coat-check, you are the majority, not the minority. It is a feeling both strange and new. Because it is essentially a mating ground, it can be cruel and pernicious, but that hardness is dealt out on equal terms. So, when LGBT people talk about gay pride, it is to this first threshold crossed, this first idea of a shared space, they mentally return.

The thought of this being interrupted, pockmarked with bullet-holes, is heartbreaking, truly. The men and women of Pulse might not have known how heroic they were before the attack. In even the most secular reading of the weekend’s massacre, they now join our saints.

Listen to the music

It’s almost impossible to overstate the importance of gay clubs to the development of pop music. Dance music as we now know it was born in gay clubs; modern pop music was shaped there: the vast majority of singles in the current Top 40 contain at least some element that you can trace directly back to them, whether the people behind them realise it or not.

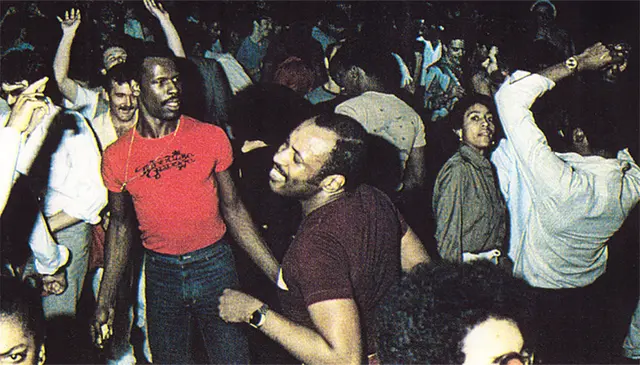

Disco, house music and a multitude of influential sub-genres; beat-mixing, the 12”single, the remix, the idea of the DJ as a star, the idea of the DJ as an author of dance music rather than someone who just played it: all were invented for, and because of, gay clubs. It’s tempting to wonder if the sheer volume of artistic invention that took place in and around them in the ’70s and ’80s wasn’t somehow linked to the clubs’ post-Stonewall atmosphere of liberation: as if the sense of freedom and possibility that came with the loosening of strictures on an oppressed culture also unbridled people’s creativity.

Certainly, the innovations came thick and fast. Francis Grasso, the man most regularly credited with single-handedly inventing the latter-day notion of a club DJ – beat-mixing records into an unbroken flow of music, declining to take requests – plied his trade at two New York clubs that straddled the rupture caused by the Stonewall riot : The Haven, “remembered as the last place cops smashed up with impunity simply because it was a gay bar”,according to Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton’s history of dance musicLast Night a DJ Saved My Life, and The Sanctuary, which Albert Goldman’s 1979 bookDiscocalled “the first totally uninhibited gay discotheque in America”.

Meanwhile, at The Loft, David Mancuso minted the idea of the DJ as a kind of storyteller, someone who could create a narrative, generate and change the mood of a dance floor through his choice of records. The remix, meanwhile, was born out of the clubs on New York’s gay holiday destination Fire Island, where model turned producer Tom Moulton watched the DJs and dancers and wondered if life wouldn’t be easier for all concerned if the tracks they played were longer and more tailored to the demands of the dance floor (it was Moulton, too, who came up with the idea of pressing them on 12”vinyl for better sound quality), although others quickly ran with the idea, not least Walter Gibbons, resident at another New York club, Galaxy 21, whose 1976 remix of Double Exposure’sTen Percentdidn’t extend the song so much as reinvent it entirely.

Long after the homophobic “disco sucks” backlash, gay clubs continued to innovate. The sound pioneered by Larry Levan at the Paradise Garage in New York fed into everything from post-punk to electro to the hugely influential experiments of Arthur Russell (the Ministry Of Sound, the first British superclub, was openly inspired by the Garage). Before the ecstasy-fuelled eclecticism of 1988’s second summer of love, DJs at The Saint were soundtracking Sunday mornings with“sleaze”, a term that could encompass down-tempo disco, Euro-pop, even Cliff Richard. In Chicago’s Warehouse club, DJ Frankie Knuckles’ refusal to abandon disco, preferring to freshen up old tracks by re-editing them, led to the birth of house music: the earliest house records were crude attempts to mimic what Knuckles was doing. Ron Hardy’s Music Box, the club where acid house was birthed, was more mixed, but still fuelled by the abandon of its gay clientele.“If you couldn’t stand to be around gays, you didn’t party in the city of Chicago,” one Music Box regular told Brewster and Broughton.“They would ask, ’Are you a child, or a stepchild?’ … If you were a stepchild, it meant you were straight, but we accept you.”

Dozens of other subgenres – from the hi-NRG that fuelled Frankie Goes To Hollywood and Stock Aitken Waterman alike, to early oughties electroclash – have their roots in gay dance floors. They are most important as safe spaces where people can be themselves, away from hate and prejudice and fear, but they have regularly invented the future for everyone.

(THE GUARDIAN)

简体中文

简体中文