Since the first vaccines were discovered, there has been skepticism and resistance towards them.

In 18th century England, for example,

clergymen openly criticized vaccines for opposing what was, according to the Church, God's intended punishment for people's sins

.

If this reasoning has now become obsolete, a significant level of mistrust still weighs on the conversation around vaccines, with many parents refusing to vaccinate their children for fear of putting their health at risk.

02:15

What's the problem?

Vaccine hesitancy – the refusal or reluctance to vaccinate despite the availability of vaccines – hasn't been so widespread as to halt the large-scale vaccination campaigns that saved millions of lives around the world in the last couple of centuries. In recent decades, however, the anti-vaccination movement has gained momentum in Western countries, becoming an increasing cause of concern for international health organizations, governments and citizens.

When a consistent percentage of the population refuses or fails to vaccinate, the risk of infectious diseases spreading is increased. A safe level, known as the "herd immunity threshold," is used to determine what percentage of the population requires vaccinations to prevent an epidemic.

For some people, vaccination is not a choice. Patients on chemotherapy treatments, people with HIV, newborn babies and elderly people are all examples of people who rely on herd immunity to protect themselves from contracting infectious diseases because their immune systems aren't effective enough.

The rise of anti-vaccination movements is a real threat to the collective immunization on which many societies rely.

Parents of unvaccinated children protested against New York state's ban on religious exemptions to vaccination for US students. Children who weren't immunized were being excluded from schools. (Credit: AP/Hans Pennink)

The issue of vaccination is complex. Some religious beliefs clash with the practice of vaccination, meaning certain groups refuse to be immunized. But the anti-vaccination movement has now reached demographics that were not traditionally opposed to inoculations.

The internet has offered conspiracy theorists and "anti-vaxxers" a platform to spread their message, sometimes relying on inaccurate information.

A key moment in the most recent resurgence of the anti-vaccination movement came in 1998, when the former British doctor and researcher Andrew Wakefield published a paper linking the MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine to autism.

Wakefield's claim was disproved and his research discredited when a journalistic investigation revealed he had received funding from groups that had brought a lawsuit against vaccine manufacturers.

What's the worst that could happen?

Since 1998, more parents have started questioning the safety of vaccines and refusing vaccinations for their children.

An academic paper

reported that in the UK, the rate of MMR vaccination dropped from 92 percent to 86 percent in six years and in Ireland the national immunization level had fallen below 80 percent by 2000.

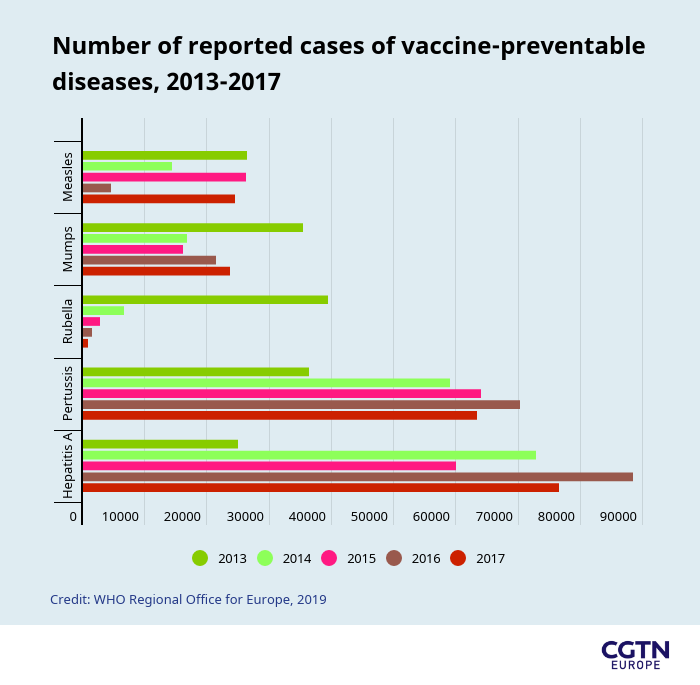

The repercussions of the decrease in vaccinations were significant, with outbreaks of measles across the Western world. Though the resurgence of other infectious diseases has been significant, measles – being a very deadly infectious disease that is easily and entirely preventable with vaccination – is a good indicator of the impact the anti-vaccination movement is having on societies.

In 2008, measles was declared endemic in the UK– meaning it was regularly found among a group – for the first time in 14 years. Albania, Greece and Czechia have also recently noted a measles resurgence after it had been officially eradicated.

Between 1999 and 2019, in the two decades since Wakefield's discredited paper, approximately 229,297 cases of measles were reported in the European Union – double the amount reported at the start of that period,

according to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

.

A measles epidemic in Romania in 2016 is so far the worst outbreak experienced in the European Union, with 59 confirmed deaths.

According to a study by Stefan Descalu

, which mentions data provided by the Romanian National Centre for the Surveillance and Control of Communicable Diseases,

most victims were individuals who had not been vaccinated.

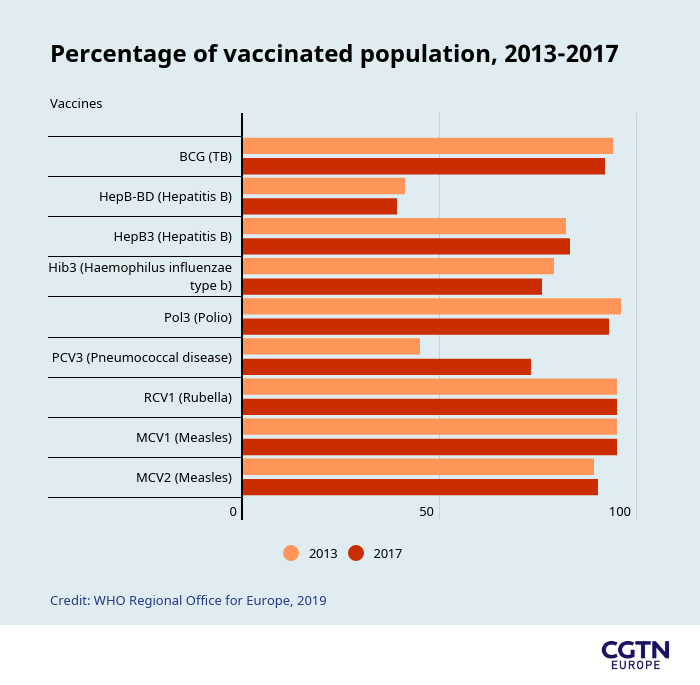

In 2014 and 2015, the targeted vaccination coverage for measles – more than 95 percent – wasn't reached in Romania and fell to an estimated coverage below 80 percent after 2015, due to insufficient national stock of vaccines and the refusal of parents to vaccinate their children. In these conditions, measles outbreaks were hard to contain.

For the wider European region, the

World Health Organization

reported that 2018 was the worst year for the continent, with 47 of 53 countries contracting measles and 72 people dying. Despite the fact that more children in Europe are being vaccinated against measles than ever before, immunization has been uneven at national and sub-national levels.

These are signs of a systemic change in the attitude of the public towards vaccines.

A study published in 2016 by EBioMedicine

reporting the results of a global survey found that the European region was the most skeptical in the world about vaccine safety, with France being the least confident country.

It is perhaps not a coincidence that France had a 462 percent increase in the number of measles cases in the country – from 518 in 2017 to 2,913 in 2018,

according to data provided by the Wellcome Trust's Global Health Monitor.

Even the US, where measles had been eradicated in 2010, suffered three large outbreaks only three years later in communities that were largely unvaccinated.

In 2019, the country reported the highest number of measles cases in 25 years.

According to the WHO, the global count of reported measles cases in just the first six months of 2019, has been higher than the full-year figures recorded since 2006.

A deep mistrust in vaccinations has led to a massive measles outbreak in Ukraine in 2019. (Credit: AP Photo/Sergei Chuzavkov)

What do the experts say?

James McEvoy, a senior lecturer at Royal Holloway, University of London and a researcher in biochemistry currently focusing on antibiotic resistance and bacterial infections, thinks we should be worried about the anti-vaxx movement.

"There have been three prongs in our attack against infectious diseases: we've had better hygiene, we've had antibiotics and we've had vaccinations," he said.

"I think if you take away any of those, then we'll start to see a resurgence of infectious diseases."

According to McEvoy, even though most of the media cover vaccinations against viral diseases, we need to consider bacterial diseases as well: "There are some very nasty bacterial diseases that we do get vaccinated against in this country, diseases like tetanus, diphtheria and whooping cough."

He added: "If people stop getting vaccinated for these diseases, then we'll see a greater incidence of these potentially fatal diseases".

"We can't rely on antibiotics to save children with all these diseases, so we'll see children dying of bacterial diseases like diphtheria. We are starting to see that already as vaccination rates dip."

Contributing factors determining whether parents are willing to vaccinate their children are misinformation, religious beliefs, value systems, personal experiences and a lack of trust in the medical establishment. To fight the anti-vaccination movement, better education around the benefits of vaccination is needed, together with easier access to vaccinations in those communities where there are insufficient stocks of vaccines.

"The anti-vaxx movement is driven by a suspicion of science and scientific authority, and I think it's up to scientists to be very clear about the benefits of vaccination," said McEvoy.

Vaccine hesitancy was identified by the WHO as one of the top 10 global threats last year

and included in the health challenges to tackle within its five-year strategic plan to ensure 1 billion more people benefit from access to universal health coverage and are protected from health emergencies.

The WHO plans to do so by targeting undervaccinated population groups and engaging with them through health workers and national authorities at a local level to counteract the influence of anti-vaxxers with credible information provided by trusted advisers.

简体中文

简体中文