As temperatures drop across northern China, centralized heating systems are slowly being switched on according to a model that has seen little change since the 1950s.

With greater urbanization and changing attitudes towards the environment in 21st century China, is the country’s heating policy outdated?

Some six decades ago, a line roughly was drawn across China following the Huai River in the east and Qinling Mountains in the west, dividing north and south and determining which parts of the country would have access to central heating in their homes.

Since then, chilly apartments, offices and factories north of that line have waited until mid-November every year for the heating to be switched on, with approximately four months of warmth provided at a heavily subsidized price. No central heating is provided to areas south of that line.

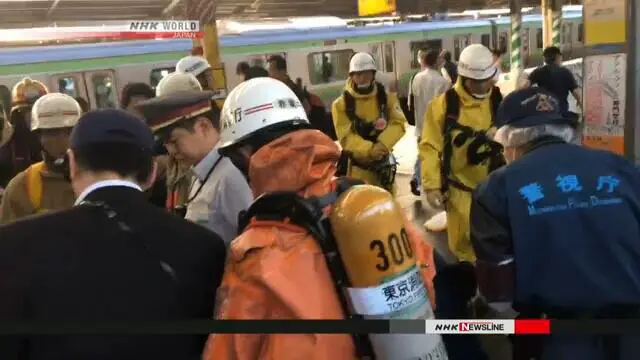

Final tests underway at one of 1,500 district heating units in Beijing ahead of the heating season, November 7, 2017.

A 2013 joint study by Tsinghua University, MIT and Hebrew University of Jerusalem found that particulate matter north of the line was 55 percent higher than in the south, and average life expectancies were 5.5 years lower.

Growing populations and urbanization rates in northern cities have piled pressure on China's heating system, which consumes some 330 million tons of coal every year.

While China is not alone in providing centralized heating – many other countries in Eastern Europe and the Nordic regions also provide similar systems in the form of district heating – would a meter-based model improve efficiency? Or can China’s current model be updated for the modern era?

Is it time to switch to meters?

A report by Beijing-based ResearchInChina released last week suggests that only 18.1 percent of the urban heat supply area in northern China is charged according to a meter. China Daily reported in 2013 that efforts to charge more consumers based on their energy use could reduce consumption by as much as 50 percent.

Wang Zhaoli, general manager of Ista Measurement Technology Services, told China Daily that "in northern China, around three billion square-meters of built-up areas can be subject to a measured charging system by installing meters. The energy saved… can supply heating to another two billion square-meters."

A switch to metering would be difficult to implement, both because of the 7.39 billion square meters of space that needs to be heated, and because the population has no financial incentive to switch away from a heavily subsidized flat rate for their heating, based on the size of their home.

Preventing waste, boosting efficiency

There are clear flaws in China’s centralized system when it comes to efficiency – the heating in most northern apartments simply can’t be switched off. In an era of property speculation (a study by the Financial Times this year estimated 32 percent of families own at least one empty home), that means a lot of wasted energy, especially when it takes 22 kilograms of coal to heat every square meter, according to China Daily.

However, efforts are being made to find greener heating sources, and countries like Sweden and Denmark provide models that show how district heating can be both clean and efficient.

This year, a huge amount of work has gone into boosting the use of natural gas in heating northern China. In a project covering 28 cities in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, coal is being phased out completely, with pipelines covering thousands of kilometers laid down to provide natural gas.

A shipment of liquified natural gas from the US arrives in TIanjin on November 6, 2017. An 83.7 billion US dollar Memorandum of Understanding on natural gas and other energy projects in West Virginia was signed during President Trump's recent visit to China.

Six downtown districts in Beijing will be heated exclusively by natural gas starting this month, with the entire project across northern China expected to boost gas consumption by 10 billion cubic meters. While the move is expected to cut carbon emissions, how can authorities help tackle inefficiency and wastage?

Denmark and Sweden provide centralized district heating to more than 50 percent of their populations, providing a model that China and the rest of the world can learn from.

They take their energy from a variety of sources, the majority of which is processed in combined heat and power stations (CHPs) – plants which can be 90 percent efficient and reprocess the heat that would have been wasted from electricity production.

Denmark has a vast network of pipes under its towns and cities to gather heat from turbines, transport facilities and factories, while many of Sweden’s building are designed to harness heat that would have otherwise been wasted. By 2035, energy harnessed just from hot computers in data centers is expected to heat 10 percent of Stockholm, according to BBC.

Harbin in northeast China's Heilongjiang Province blanketed in snow, November 12 2017.

According to China Daily, only seven percent of buildings in 2013 met national energy-saving standards. However, adoption of CHP technology doubled between 2008 and 2012, and as of 2016 provided 13 percent of energy across the country, according to Mordor Intelligence.

As authorities continue to wean the country off coal and move towards cleaner energy sources, other countries around the world show that with innovation and public support, China’s centralized central heating system can be modernized and made greener and more efficient.

(CGTN)

简体中文

简体中文