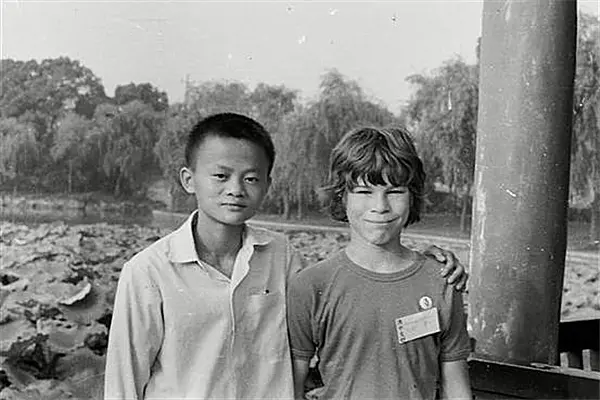

(THE WALL STREET JOURNAL) In 1980, a scrawny Chinese teenager approached an Australian tourist named David Morley in the southern Chinese city Hangzhou and asked to practice English. The chance meeting would prove a pivotal one for Ma Yun, who would later be known to the wider world as Jack Ma.

In “Alibaba: The House that Jack Ma Built,” which begins sale April 12, author Duncan Clark explores how that early friendship helped prepare Mr. Ma to found China’s largest e-commerce company, Alibaba Group Holding Co., two decades later. Mr. Ma honed his English through years of correspondence with the Morley family; his language studies paved the way for his first trip to the U.S., where he discovered the Internet and was inspired to start a web company. The Morleys became so close with the scrappy young man that Mr. Morley’s father bought him his first apartment. It was luck, says Mr. Clark, but “Jack made his own luck.”

Mr. Clark’s new book helps fill a gap in the high-tech sector’s canon. The lives and personalities of key American high-tech entrepreneurs have been detailed in biographies such as Walter Isaacson’s “Steve Jobs” (2011), Nick Bilton’s “Hatching Twitter: A True Story of Money, Power, Friendship, and Betrayal” (2013), and Brad Stone’s “The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon” (2013). In contrast, there have been few English-language books on Asia’s high-tech pioneers, although the companies they founded rank among the world’s largest.

Mr. Clark is a former investment banker who runs the Beijing-based tech consultancy BDA. He draws on two decades of experience working in China to write about Mr. Ma and the evolution of the Chinese Internet. The book also explores more broadly how entrepreneurship developed in a country where just a few decades ago private business was illegal.

China Real Time spoke with Mr. Clark in Beijing about the book. Below are edited excerpts from the interview:

Why did you decide to write a book about Alibaba?

There are a lot of interesting things to discover about China through the prism of Alibaba. There’s the story of the Internet, but also the story of entrepreneurship in China, particularly the rise of the south of China — what I think of as the entrepreneurial side of China. Zhejiang province, where Alibaba is headquartered, is really the crucible — the Mecca, if you will — of entrepreneurship in China.

What makes Jack Ma unique as an executive?

Jack has this ability to make you feel that he’s speaking to you, even in a room with a few thousand people. You feel yourself swept along.

I often find it interesting when Jack is speaking to turn and see the people he’s speaking to. I’ve seen grown investors cry. He does it in English as well as Chinese.

A memorable story from the book was about a conference for entrepreneurs held in 1984 by the government of Wenzhou, a city in Mr. Ma’s home province Zhejiang. Some of the entrepreneurs who were invited refused to attend, fearing arrest. Some who showed up brought toothbrushes in case they were detained. 1984 really wasn’t so long ago. How did Zhejiang transform so quickly into a hub of private enterprise?

Wenzhou and Yiwu (another Zhejiang city that has become a trade hub) are very hardscrabble places. So this level of risk appetite seems to be higher than anywhere. They were the most gutsy people in China.

I remember in 2000, when Jack hosted this big conference. He had the governor of Zhejiang and the vice governor there. I spoke to the vice governor and I asked her, “How do you treat the private sector in Zhejiang?” She said, “We just stay out of their way.” It was so refreshing for me.

I think Jack being born into Zhejiang was probably the best thing he could have done. He wasn’t born into wealth. He wasn’t born into a privileged family. But he was in a very good place, strategically, to do commerce.

Alibaba weathered the dot-com bubble bust in 2000 just a year after it was founded. Some say China’s startup valuations are bubbly again. Is there another bubble?

The first dot-com bubble was clearly a bubble, because none of the companies were making money. Today the difference is there are companies making real money. But investors really want to chase the winner. It’s winner take almost-all. That’s why there’s a temptation in some places to fuel with subsidy or, perhaps, exaggerate.

There is a sense that these companies represent the gateway to the emerging middle class market of China. If the Chinese government is able to create the conditions for this consumer class to continue to grow, then some of these companies are going to be inheriting the earth. But not everyone can win.

Your book recounts a little-known story of Jack’s early friendship with an Australian pen-pal David Morley and his father Ken Morley. They helped teach him English and even bought his first apartment. David Morley provided some early photos of Jack for this book. How did you track the family down?

I started calling these random David Morleys in Australia. In one part of New South Wales, there was this yoga studio. I emailed the website, and he’s like, “Yep, that’s me. How can I help?”

Ken Morley was a Communist. He was a union organizer who had brought his family here (to China) in 1980 to visit the socialist paradise. The irony of this – Ken himself had said he may have created this capitalist icon, but it wasn’t his intention. But he has a lot of affection for Jack.

Can you talk a bit about the writing and research process for the book? How did you get it all done in a year?

I was concerned that I might miss the window if I took too long to write it. After I got the deal, I met with some journalist friends in Beijing, and they were like, “So are you taking the next two or three years off?” I was horrified to understand that one year is really not that much time.

I’d thought I would get a lot from (previous Chinese-language biographies of Jack Ma), but I really didn’t. I realized pretty quickly I had to do the research myself (with the help of research assistants). But then I realized I had a lot of resources. One was that my classmate from Morgan Stanley was the first investor (in Alibaba) – Shirley Lin. She was super helpful. She’d never really spoken much about it before. Shao Bo, the founder of Eachnet (an early rival of Alibaba), is a friend. We play tennis together. He still beats me.

简体中文

简体中文