In the history of China's space program, other than humans, silkworm larvae were not the first creatures to venture into the great beyond.

When the program was inaugurated in the early 1960s, a wide variety of animals got a head start.

In July 1964, the pioneers were a group of white mice on board China's first sounding rocket, T-7AS1, which carried measuring instruments. Two years later, the mice were followed by two dogs.

Space lab

The chapter that prepared the way for China's 2016 manned space exploration was opened by the successful blastoff of Tiangong II on Sept 15.

The 8.6-metric-ton space lab, the country's largest space asset, was designed to provide a comfortable, working environment for astronauts to conduct 14 different, wide-ranging experiments.

They included examining the science of aerospace materials, cultivating plants, applications for robotic arms, and an experiment to see if silkworms can thrive in space.

Shang Mingyou, an engineer at the space laboratory system, told China Central Television that Tiangong II was built with a lower noise level than its predecessor, Tiangong I.

Measures were taken to reduce the noise emitted by moving fans or other rotating parts. The noise level was kept within 60 decibels, a safe level that did not hamper conversation or distract the astronauts while they conducted the tests, according to Shang.

Breakthroughs

In the past decade, China has made a number of breakthroughs in manned space missions.

The first Chinese astronaut went into space aboard Shenzhou V in 2003. Shenzhou VII, with a crew of three, including Jing Haipeng (commander of China's latest space mission), was launched in 2008, and astronaut Zhai Zhigang conducted China's first spacewalk.

In 2013, Shenzhou X, with three astronauts on board, roared into space on a 15-day mission.

The Shenzhou XI mission, which started in October and concluded last month, is being seen as an important milestone in the country's program of extended space exploration.

A number of projects are ongoing and others are ready to be rolled out, including lunar probes, the BeiDou Navigation Satellite and the Gaofen observation satellite program.

All are scheduled for completion by the end of the decade.

By 2020, more missions are expected to be undertaken, and the nation also plans to eventually send a probe to land on Mars.

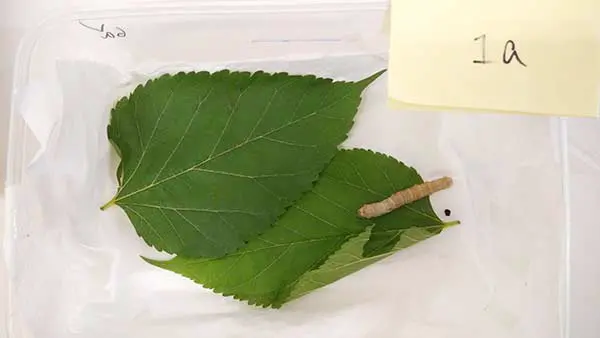

Astronaut Jing Haipeng displays a capsule used to house silkworm larvae during the 33-day mission aboard Tiangong II. Photo: Xinhua

Blueprint

The blueprint proposed by the students was a large, square, transparent box fitted with an electric fan to extract the feces excreted by the larvae. In terms of shape and size, it was different from the end product forged by CASC that went into space and contained six compact capsule-shape containers, each housing an individual larva.

The principles of the capsules were not a major departure from the students' original proposal. Speaking to China Daily when they revisited their prototype, the students said many larvae died of dehydration during the early stages of the experiment because they were fed stale mulberry leaves rather than fresh ones. That led to the students proposing replacing the leaves with moistened food pellets.

Later, CASC optimized the students' idea. Instead of using food pellets, the engineers modified the mulberry leaves into a greenish paste that locks in moisture. The paste was then smeared on the insides of both ends of each capsule, allowing the larvae to crawl through the tubes and feed, according to Zhao Danni, the CASC engineer who designed the capsule, in an interview with CCTV.

The inner walls of the capsules were also sheathed in shock-absorbent foam made from aerospace-grade polyurethane and designed to prevent the larvae from coming to harm as the spacecraft juddered skyward, she said.

Once Shenzhou XI had completed its automated docking procedure with the orbiting Tiangong II on Oct 19, the experiment was ready to begin.

"We observed, took care of the larvae and spruced up their homes on a daily basis," Jing said, in a video taken aboard the space lab. He and Chen shared "fatherly" duties for the larvae for the first eight days of the mission, from Oct 19 to 26.

The student team explained that the excrement had to be cleaned up frequently because close contact with germs could have endangered the larvae during their days in space.

The original idea was to use an electric fan to suck away the waste product, but the astronauts tweaked the approach to save themselves time and energy. In a video shot onboard Tiangong II and released by Xinhua News Agency, Chen can be seen unscrewing the top of a capsule and shaking out black bits of feces that then drifted up into a plastic bag.

In the same video, Jing, the mission commander, was seen drifting weightlessly and carrying a pocket-size capsule that held one of the six larvae.

Through the windows of the six capsules, he observed and assessed how the larvae reacted and grew in space. "Look. The device is the home of the larvae," he said. "And in fact, they are now in their second home, which is the Tiangong II space lab, 393 kilometers above the Earth."

The experiment was one of three projects jointly designed by mainland space engineers and the Hong Kong students. Their endeavors were to become part of China's longest manned space mission.

The six larvae aboard Shenzhou XI were sent into space on Oct 17. The day before the launch, Wu Ping, deputy director of China's manned space engineering office, told a media briefing that the tasks undertaken during the 33-day mission, including the silkworm experiment, would be "engrossing" and "well worth seeing".

Triumph

The larvae fulfilled the hopes of the students and the mission scientists, as five of the six succeeded in spinning cocoons. The experiment was a triumph for all involved.

"Aerospace experiments were something very farfetched, they used to be a visionary dream to students in Hong Kong," said Mak Tang Pik-yee, executive director of the Hong Kong Productivity Council, who was a member of the organizing committee of the 2015 Space Science Experiment Design Competition.

However, the astronauts carried through the students' dreams, sending their designs from Earth into space, she added.

The larvae were frozen following their return to Earth on Nov 18. They will remain dormant in low-temperature conditions while the groundwork is laid for follow-up experiments into the effects of microgravity on spun silk.

"There was a time when we would never have anticipated that the students' ideas could be brought into space," said Chow Wing-hei, teacher and project adviser of the silkworm experiment. "But we're all now basking in the glory of having those ideas tested and proven successful in space."

In the history of China's space program, other than humans, silkworm larvae were not the first creatures to venture into the great beyond.

When the program was inaugurated in the early 1960s, a wide variety of animals got a head start.

In July 1964, the pioneers were a group of white mice on board China's first sounding rocket, T-7AS1, which carried measuring instruments. Two years later, the mice were followed by two dogs.

(CHINA DAILY)

简体中文

简体中文