The first time I visited Kennedy Town, atthe northwestern end of Hong Kong Island,the sea still ran up to the Praya and there were stone-pillared arcades in Belcher's Street. That was in 1993. Someone had told me about (relatively) cheap flats at the far end of the neighbourhood, where the trams turn to begin their journey back alongthe island, in two blocks owned by the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The address was Victoria Road, and as I'd just left a tiny flat in Victoria Road, London, for the single year I intended to be in Hong Kong, the symmetry felt appropriate.

But it turned out that Tung Wah had a strict two-year, no-break-lease policy; so I hopped round the city until 1996, when a friend mentioned that Tung Wah had introduced the more usual one-year (plus two months) break clause. That's why I remember the date I moved in: May 15, 1996. In 14 months, it would be July 15, 1997, a fortnight after the handover of the British territory back to China, and I'd certainly be on my way.

A couple of days before the move, I went to the flat with a tape measure and heard about a gun battle that morning in the streets below. Hong Kong's most-wanted criminal, Yip Kai-foon, also known as Goosehead, notorious for spraying bullets from an AK-47 during robberies,had been captured by a couple of policemenwho'd seen him coming ashore and initially assumed he was an illegal immigrant. (He was paralysed in the shoot-out, and is currently in Stanley prison,serving a 41-year sentence.) I can remember looking down at the harbourfront and wondering if a move to this wild west was such a good idea.

"Is it safe where you are, Fionnuala?" my father had asked anxiously on the phone from Omagh, in Northern Ireland. The question had nothing to do with Yip and everything to do with family history.

When I was a child, we'd moved around the south of England, then to Northern Ireland - a region of the United Kingdom where people referred to England as "the mainland" - just as the civil-rights movement was getting peacefully under way. Things had quickly, appallingly, fallen apart. Several times, bombings left us with nowhere to live. Aged 16, after we'd survived an explosion five days earlier, I wrote in my new diary on January 1, "10th time we have moved house".

So I told my father it was safe. It's true that, at first, I was alarmed by the ambulances and police vans that would appear every evening in neighbouring Davis Street, but it turned out the drivers were buying takeaways from a well-known dessert shop. My mother, an inveterate letter writer, was reassured by the address itself: Victoria Road, Kennedy Town was a more graspable concept than previous residences in Sai Wan Ho Street, Shau Kei Wan or Wun Sha Street, Tai Hang. Naturally, my parents assumed the Kennedy in question was JFK; they'd never heard of Sir Arthur, governor of Hong Kong (1872-1877) and, as it happens, a native son of Northern Ireland.

I hadn't known about governor Kennedy either. Nor had I known that, before him, the area was known as Lap Sap Wan - Rubbish Bay. From the beginning, all the things you didn't want in a growing city were dumped in this extreme corner of the island, including plague victims, smallpox sufferers, lepers, corpses and various noxious industries such as fat-boiling. I once read a news item about a 1920 conflagration in Kennedy Town in which 34 people died; the fire had begun in a building on the Praya that stored "pig and human hair". The Sanitary Board was constantly on the alert about diseases (anthrax, trypanosomiasis, black quarter) detected in the Kennedy Town Animal Depot. The worry, always, was what might come from China.

Moving to Kennedy Town for the last year of British rule, under governor Chris Patten (who'd been a Northern Ireland minister in Margaret Thatcher's time), heightened my interest in local history. A stone marking the city's boundary in 1903 stands near the Tung Wah buildings, yet Kennedy Town felt beyond the pale, in the literal, and Irish, derivation of that phrase: it was beyond British rule. There were a few foreigners around - some of them working for theSouth China Morning Post, journalists having a keen sense for a bargain - but if taxi drivers saw me they usually slowed down in the belief that I was lost.

This was funny because it was the first time in my peripatetic life that I felt found. Kennedy Town was, definitely, where I wanted to be.

In those days, the expressway to Central wasn't finished and the backstreet traffic was chaotic; you needed to know the bus routes (especially the triad-controlled, red-minibus network) or be prepared to squeeze onto a tram. As a result, the neighbourhood felt self-contained, an outpost within an outpost. On summer evenings, the pyjama quotient among older men out for their strolls was high, and the children ran up Smithfield to the public swimming pool in their bathing suits. The pavements were strewn with drying, salted fish; the sea was a presence glinting at the end of every undeveloped street.

I went walking at night, often making notes, and no one gave me a second glance. In mid-1990s China, people goggled at foreigners in open disbelief but in Kennedy Town, the locals ignored Westerners. I recognised how they simultaneously saw and chose not to see the potentially troublesome stranger; it was exactly what people in Northern Ireland did with British soldiers at checkpoints. I had my own colonial history so I didn't mind, and I liked being on invisible patrol. When the Union Jack flew, hilariously, from Kennedy Town's firestation to mark the queen's official birthday (a public holiday here, but not in Britain, nearly 10,000km away, where the queen actually lived), I thought of a sign at my laundrette, listing charges for blankets and eiderdowns: "guilt counted separately".

One February morning in 1997, the ships' horns in the harbour suddenly blared over the city and, when I looked out of the window, a Chinese flag was flying on top of the building next to the Chinese Merchants' Wharf. Deng Xiaoping, architect of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, had died. He hadn't lived to see the handover four months later but the fact of it - one country, two systems - was already in place. Only the ceremonial trimmings, concluded in incessant rain, were left.

I stayed on. Hong Kong was perfect for those of us who might have been inclined to find new places, because you didn't have to go anywhere: the flag, the coins, the stamps, the law, the leadership, the army changed around you while you stood still. Yet my regal Victorian address remained, and there was no uprising and no backlash. I once saw a Kennedy Town red minibus with the words "colony elimination system" written on the side; it was advertising a pest-control company.

Although I still dislike thunderstorms and fireworks, I've learned to live with both. On winter nights of open windows, I used to wince at the pigs' shrieking as they arrived at the Kennedy Town abattoir, but that closed. In its place appeared newly seeded grass, and a youthful cluster of saplings. For years, I directed visiting friends' attention to its classic Hong Kong-transience sign: Cadogan Street Temporary Garden. I'd always think: which will go first - the garden or me?

NOW THE GARDEN IS GOING.At least, that's the plan. The government wants to uproot it, decontaminate it and redevelop it, probably for luxury housing. Estimated cost, according to the Civil Engineering and Development Department: HK$1.1 billion. The decontamination is a puzzle. For almost 20 years, we've been enjoying it, 200 trees have flourished in it, but it seems the land is tainted from previous use and will take seven years - a number from a spell or a fable - to purge.

Petitions have been circulated, picnics have been held, meetings with Legco arranged.

"They're not political, and I think that kind of purity is good for preserving the park," said Democratic Party district councillor Hui Chi-fung, about the Kennedy Town organisers. "But they've done everything and they didn't achieve anything. That's when I realised they needed more direct action and way more attention."

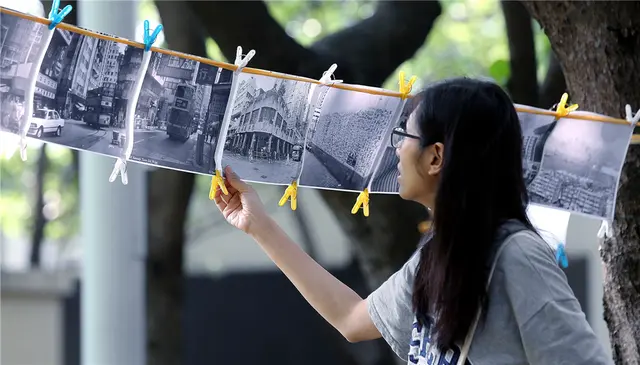

It was May 1, Labour Day. We were talking in the garden where Hui, who's 33 and a graduate of the Occupy movement, had pitched a tent in mid-April; he planned to stay for 30 days as a protest. Behind him, a man was pegging black-and-white photocopies of old Kennedy Town scenes to the bushes. I remembered some of them - last-century street views before The Merton, The Belcher's, The Cadogan began piercing the skies.

As part of his attention-grabbing initiative, Hui had arranged an outdoor screening ofTen Years, which won the best film prize at April's Hong Kong Film Awards and is banned in China. The production company had intended to charge a fee but, as Hui explained, "the goal was so meaningful" that costs were waived. A couple of policemen were hovering nearby. When I asked, Hui said, no, he deliberately hadn't sought approval.

"It's a necessary disobedience to challenge authority. If they have the authority to demolish this park, why don't we have the authority to use this park?"

When my father in Omagh had asked me, 20 years ago, if my new address was safe, his concern had been misplaced. Early one Sunday morning in August 1998, a week after I'd returned from a visit to Northern Ireland, I'd turned on the BBC World Service to hear that 29 people and two unborn babies had been killed by a carbomb in Omagh, the worst single incident in the Troubles. My father had been in the town, survived, suffered depression, and would never be the same again.

In those pre-internet days, I'd had to wait a week for the local newspapers my mother posted to Victoria Road. By the time they started arriving, it was the Hungry Ghosts season, and ash from the burned offerings of Hell banknotes blew around Kennedy Town like black snow. I cried every evening for 10 days in my flat, reading about the devastated town I'd known; the only way to cope with sorrow's suffocation was to get out and mingle with the living in another community, to watch the faces in the restaurants, in the godowns, at the mahjong tables, to walk along the seafront, up the steep steps by the old Lo Pan Temple, under the banyan trees of Forbes Street. In Kennedy Town, life with all its vividness went on, safely.

That time marked a change. I stopped being invisible. People waved. One day, I heard a wolf-whistle and stopped in surprise (it had been a while) and a mynah bird, head cocked, gave me a knowing look. It was in a cage outside a barbers' shop on the corner of Hau Wo Street. After that, for years, I used to whistle back, then greet the three barbers and their customers; and once, on a stifling afternoon when I couldn't stand the weight of my hair, I went in for a quick trim (HK$20).

A few years ago, when a handwritten notice in Chinese appeared on its shutters, I didn't need a translation; with the news that the MTR was coming, rents had been going up everywhere and I guessed that the barbers, like so many others, were leaving. On their last day, I took them cakes and they sat in their professional chairs - 100 years old, they said - and talked about how they'd come to Hong Kong from Guangzhou in 1951. When they'd arrived in Kennedy Town in the '70s, cattle still walked through the streets to the abattoir.

The bird was gone: they hadn't wanted it to die in a cage so they'd set it free on Mount Davis.

A collector bought those chairs. When the old rattan shop round the corner from my building closed, representatives from M+, the soon-to-be museum for visual culture, bought stock at the street auction. Kennedy Town was disappearing. A developer who'd put leaflets in our mailboxes about its new property in the adjacent street referred to the district as "West SoHo". Yet, at the same time, now that it was more connected to the rest of Hong Kong, now that more strangers from Chinawere arriving, and resentment and suspicion (and prices) were rising, local people harked back to a past they'd barely known as a bulwark against a future they couldn't control.

Naturally,the protesters at the Cadogan Street gardenorganised historical tours of Kennedy Town and, a few Sundays ago, I joined one. It was in Cantonese and although I could guess a few bits, there were many tricky words peculiarly relevant to Kennedy Town that a volunteer had to look up on Google translate: "black death", "coal", "hemp", "offensive industries", "slaughterhouses".

At one point, I saw one of the local recycling women waving; in my early days, she'd glance away when I said hello until persistence won out. A few years ago, the street corner where she always sat remained empty and I was concerned enough to make inquiries; she was visiting relatives in Argentina, as it turned out.

As we looped back to Victoria Road, I was thinking about Alexandre Yersin, the Swiss-French man who'd discovered the plague bacillus in a matshed in Kennedy Town in 1894, on a spot which would have been almost opposite the Cadogan Street garden. For centuries, it was believed that plague was caused by a miasma, a poisonous vapour in the air. I thought maybe the garden should be kept just as it is and named in honour of Yersin, who knew that some sicknesses aren't nebulous but have a provable cause and should be wisely treated before there's a fatal epidemic.

On Hui's last day, May 16, I went to watch him and his supporters packing up the tents. It was, as he ruefully agreed, the most beautiful afternoon of a singularly wet spring; the Indian almond trees in the garden rustled lushly, the birds sang and elderly residents - some accompanied by helpers, wired to their earpieces like part of a security detail - scrutinised proceedings. It was 20 years and a day since I'd moved to Kennedy Town, by far the longest I'd ever lived in one place; the helpers, then, had mostly been employed to look after the young, not the old. Now a whole generation has grown up.

On May 10, Hui had camped outside the Planning Board in North Point to hand in a petition by the following morning's deadline. It had 3,235 signatures, not counting those online. Otherwise, he'd spent 29 nights being bitten by mosquitoes, then being woken at dawn every morning by the residents of Kennedy Town for whom the garden is part of an enthusiastic daily ritual. And, after all that, there's a pause.

Legislative Council elections are in September. If the Planning Board hasn't decided anything by then, budgets will have to go back for re-approval - in which case the clock will be reset.

简体中文

简体中文