For 35 years, Zhang Yuxiao has been known for her one role: being a mother.

A typical day for the 65-year-old revolves around looking after six school- and college-age children who call her mom, even though none are her own children. It is in the same home where Zhang has raised 25 Chinese orphans since the 1980s.

One day in 1986, a radio newscast changed Zhang's life forever.

"I heard on the radio about the children who lost their parents, and I wanted to give them a home," she told CGTN. "At that time, being altruistic and doing good for society was an honor."

Zhang is one of the 16 "moms" – women who have remained single and childless by choice to provide full-time foster care for orphaned children at the SOS Children's Village in Yantai City, east China's Shandong Province. There, each foster mom leads a temporary family where five to eight children live under their care until they leave the village for work or college.

Across the country, more than 3,000 orphans have grown up in SOS Children's Villages in 10 Chinese cities, some 400 in Yantai.

In 1986, when the international organization, which supports children without parental care, opened its Chinese branch in the coastal city, Zhang was one of the first foster moms to sign up.

SOS Children's Village in Yantai, east China's Shandong Province pictured, January 1, 2021 /Courtesy of SOS Children's Village

'Guilty about lying to my own mother'

When Zhang first arrived as a 30-year-old single woman, the decision not to marry and mother her own children – a prerequisite for new foster moms to join – was inconceivable to many people at the time, especially her own family, Zhang told CGTN.

"My sister and brother cried because they could not understand it, and I had to keep it a secret from my mother," she said. "But I feel proud because what I'm doing is out of love."

After moving to Yantai from another town in Shandong, Zhang told her mother that she met a local man and was going to get married. That lie continued for decades, and when her mother passed away, it became a regret Zhang still carries in her heart.

"I'm a mother to 25 children. But I feel guilty toward my own mother," Zhang said. "My mother would've loved these children as I do if she were still alive."

Zhang Yuxiao pictured at the Children's Village in late 1980s /Courtesy of Zhang Yuxiao

Zhang's story is not uncommon among older moms in the village, as many of the women have had to hide their work and single status from families. But attitudes are changing as Chinese society becomes more tolerant toward single women, said Yang Ning, the director of Liaison and Cooperation at SOS Children's Village in China.

"The village is another choice for unmarried women who love kids," Yang said. "In a sense, the Children's Village has witnessed the transformation of Chinese women's choice in regard to marriage and motherhood over the past three decades."

A 24/7 job, but worth it

Daily life in the Village as a full-time mom is mundane and exhausting, and taking care of several children at once is no walk in the park.

Before joining the village eight years ago, Cao Furong, 51, worked at a processing plant.

"When I was working in the factory, I didn't have to think about anything after finishing my work. After I became a mother here (in the village), there is always something on my mind," Cao said.

As workers for this charity, which is supported largely by social donations, foster moms in the village earn a humble monthly salary of 3,000 to 4,000 yuan ($470-630).

While love for children is a common motivator for single women to join the community, dedicating a lifetime to caring for children that are not one's own is certainly not for everyone.

Some moms may contemplate quitting when they approach middle age or have health problems, Yang noted. But few have gone through with it, "because the bonds they have with the children always held them back," Yang said.

That thought crossed Cao's mind once when she fell ill, but one of the children she was looking after changed her mind, she told CGTN. As Cao lied in bed with a fever, an 11-year-old girl came into the room with a basin of hot water to help Cao bath her feet.

"She said to me, 'mom, are you feeling better? Please don't leave me,'" Cao said. "At that moment, it was all worth it."

Cao said her plan after retirement is to accompany the children as long as she can.

For Zhang, who had nine children in her house at one time, watching the little ones grow into responsible adults and upright members of society, who then have families of their own, makes it all worthwhile.

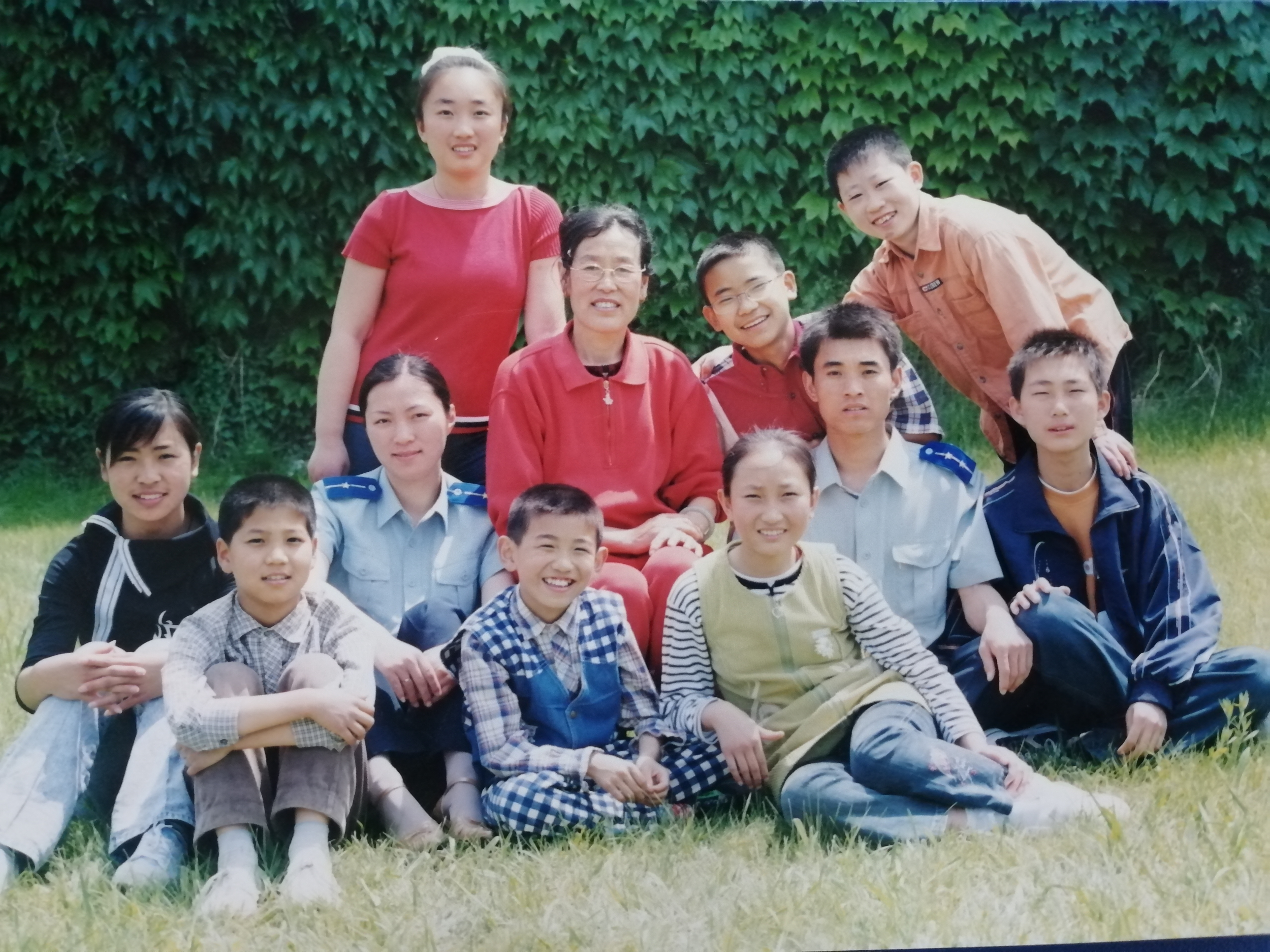

Zhang Yuxiao (C) is pictured with some of her foster children. /Courtesy of Zhang Yuxiao

In 1998, Zhang's oldest son, Zhang Jiancheng, who was serving in the army, received a national honor for his contribution to China's disaster relief effort during the country's worst flood.

"I worry a lot, in my heart and in my mind. But I'm happy because I have a big, loving family," she said.

Today, Zhang is a proud mother and grandmother with many families who would visit her in the village during the holidays.

"I feel luckier than a real parent," she said. "My children are everywhere. They always have a home here."

'All I want for them is to be a good person'

The village rejoiced last summer when a letter from Beijing arrived. An An, a teenage boy in Li Guiying's home, was accepted by the Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications.

An An is the latest

Gaokao

success story in Li's home after an older boy got into Xidian University in Xi'an the previous year. So far, all children in the village have graduated high school and around 40 percent have gone to college. Nevertheless, admission to a top university is still considered remarkable for teens in foster homes.

Before she came to the village in 1990, Li was an English teacher. The 58-year-old is often praised for creating an optimal environment for studying in her home, which she has filled with books she bought for the children.

Li has kept a blackboard in the living room for yearswhere she would write down new English sentences for the children to learn. One day, a first-grader pointed out to Li that she misspelled the word computer. "He was right, and that's when I realized it was working," she said.

Li Guiying teaches her children English in their home. /Courtesy of Li Guiying

The former educator insists that it's the children's willingness to learn that has made a difference. Instead of taking credit for her children's improved grades at school, Li counts herself lucky to have older children like An An as role models for their younger brothers and sisters.

"I've never forced them to learn. My children never had a day of after-school tutoring. They did it all by themselves," Li said, adding that she also has things to learn from the youngsters, like using a cellphone.

Like all parents, the foster mom gets anxious every now and then over her children's education. But Li said she is happy and grateful, and hopes that her children will know gratitude when they grow up.

"All I want for them is to be a good person and give back to society," Li said. "What's more to expect?"

简体中文

简体中文