A Billion Voices: China's Search for a Common Language tells the story of the creation of Putonghua, or Mandarin, which is an interesting read for both Chinese and foreigner students of the language.

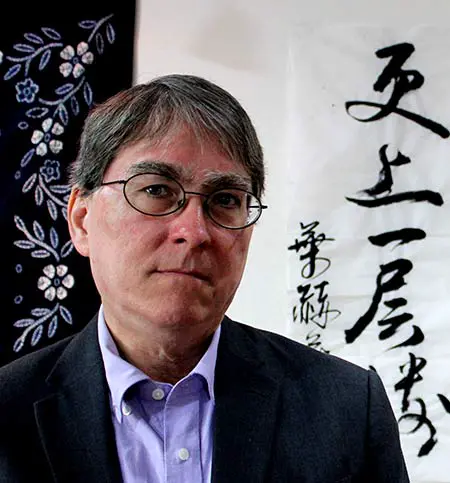

The book is written by American linguist David Moser, who has spent more than 30 years studying Chinese. It is now only selling as an e-book but will be available in paperback in October.

Currently, Moser is teaching at Capital Normal University in Beijing, where he coordinates a program for foreign students coming to China for summer courses.

There are more than 100 million people studying Chinese overseas, according to Xu Lin, executive director of the Confucius Institute, which provides Chinese language classes around the world.

"When people say Chinese is so difficult, what they really mean is that Chinese characters are difficult to learn," says Moser.

"I think there's great confusion even among Chinese people between spoken language and script."

Unlike most European languages which are largely phonetic, Chinese has a writing system that is separate from speech, making it possible to pass on the knowledge within different regions and through generations. Nevertheless, the written language wenyanwen in the past, or literary language text, is extremely difficult to learn for ordinary people.

When it comes to the spoken language, there are more than 100 dialects, among which many are unintelligible between each other, which makes communication difficult between people from different areas.

In the book, Moser takes readers back to the early 1900s to see how Chinese intellectuals tried to reform the language after the fall of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

"It was a group of very smart people getting together in a room to figure out how to form a unified language and to solve the problem of literacy," says Moser.

"Since they didn't have the scientific tools, it took them a long time to do it, and they made some mistakes along the way."

One of the radical initiatives was to replace the Chinese characters with the Roman alphabet proposed by many intellectuals during the May Fourth Movement, which advocated Western notions such as "science" and "democracy".

During the 1930s, such a project of Romanizing Chinese characters was even put into practice in Yan'an, where there were around 300 publications with a phonetic system called Latinxua Sin Wenz, or Latinized New Writing, circulating in the area.

When American journalist Edgar Snow visited China in 1936, he even found that the Communist Party of China had already published a pocket dictionary of the phonetic system of Chinese, and was experimenting with teaching it to a class of young students.

But the method lasted for a very brief period of time. It was abolished completely in 1955.

What wins out among plans to Romanize Chinese language is pinyin, which literally translates as "spelled sounds". It is used to denote the sound of each Chinese character using English alphabet and four diacritics for tones.

Besides the reform in the writing system, Moser also traces the little-known process of how people unified over 100 of so-called dialects into what is widely used now-Putonghua, or the common speech.

Moser captures the tensions between Putonghua and dialects, because some of the dialects could be arguably considered as another language.

Many dialects are dying out as there are fewer people speaking them nowadays.

Near the end of the book, Moser also touches upon how the internet has been affecting the Chinese language: A lot of internet slang and a mixture of foreign and Chinese compounds have emerged, and they are used by young people.

Moser says tracing the reform of Chinese language along the way is a process for foreign learners to understand how Chinese works.

Almost 25 years ago, five years after Moser began to learn Chinese, he wrote an article titled Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard. The article is still popular among foreign Chinese learners.

"Yes, Chinese is still hard, but (now) we have digital tools and dictionary to help us learn it," says Moser.

(APD)

简体中文

简体中文