Tiny electronic security tags are being hidden on sheep, as livestock rustling from UK farms becomes an increasing problem.

The number of sheep stolen from fields and hillsides went up 15% at the start of

lockdown

, with thefts of all animals now costing farmers an estimated £3m a year.

The losses are blamed on

black market meat sales

and a few dishonest farmers who want to swell their own flocks or take prize animals for breeding.

Image:Livestock marking paint mixed with microdots, only visible under a microscope, is applied to the sheeps' backs

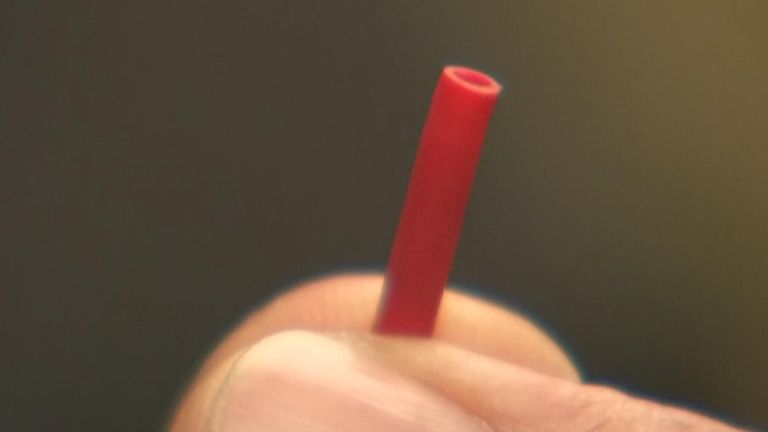

Image:Transponders are hidden in the animals' fleeces

The forensic anti-theft system uses radio frequency identification (RFID) tags glued into the animals' fleeces, and livestock-marking paint mixed with microdots only visible under a microscope.

It was invented by John Minary from York-based business TecTracer, who adapted technology he developed to help protect church roofs from lead thieves.

"Each microdot bears a unique code to this farm, and those codes are all stored on a database," he said.

Painting a stripe of blue marking paint on to Texel ewes with sheep farmer John Murray at his Brown Hill House farm in Westerdale, North Yorkshire, Mr Minary said traditional identification methods, from horn markings to electronic ear tags, are easily removed by rustlers.

"If these sheep were to be stolen, it sends out alerts to other stakeholders, auction marts and abattoirs, and gives us the ability to be ahead of the thieves," he said.

The hidden RFID tag can be picked up by the same scanners used by auction marts to log animals in and out with the data in their ear tags, with the microdots offering a second method of forensic identification.

Image:Farmer John Murray says when his animals return to the farm, there are usually some missing

Image:Livestock theft cost UK farmers £3m in the last 12 months

Mr Murray, whose farm displays warning signs to tell thieves his flock is electronically protected, says the system has stopped sheep thefts from his remote moorland grazing where up to 20 a year have disappeared in the past.

"They run on about a mile of moorland either way from their base on the farm and you cannot check these animals daily," he said.

"The key thing is the carcasses are not there on the moors, so somebody must have taken them," he said.

简体中文

简体中文