26:55

**CGTN Europe's podcast **

**The Answers Project ****seeks to solve some of the world's most burning ethical, scientific and philosophical questions. In this episode, journalists Stephen Cole and Mhairi Beveridge discuss one simple question: **

Are we alone in the universe?

For millennia humans have gazed into the night sky and wondered if there is life on other planets, but for all our scientific advances, we are still largely limited to theoretical guesswork.

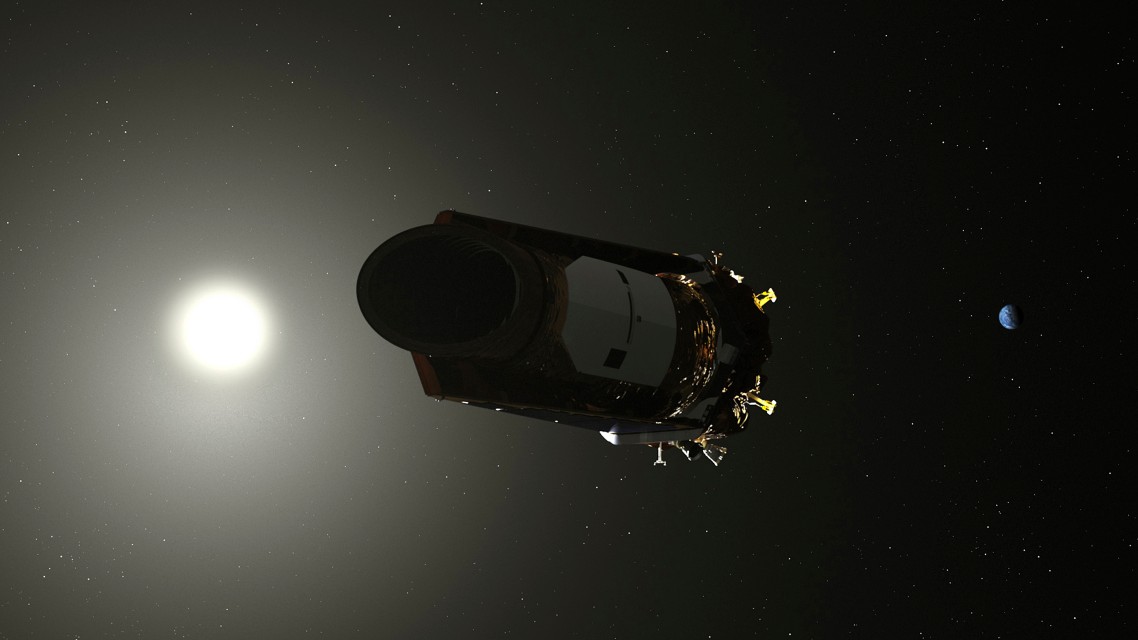

One investigatory avenue has been to search for planets like our own. In 2009, NASA launched the Kepler Space Telescope with the aim of finding Earth-like planets orbiting a sun-like star at the right sort of distance.

That distance is known as the "Goldilocks Zone" – not too hot and not too cold, specifically for liquid water, seen as essential for life as we know it. Kepler's results suggest there may be as many as 40 billion Earth-style planets out there with the right conditions for life. But what does that mean?

READ MORE

The Czech actor turned gravedigger

Testing face masks on mannequins

Secrets of 'world's first computer' revealed

Didier Queloz is the right sort of man to answer that question. The Swiss-born Cambridge University professor jointly won a Nobel Prize for Physics after discovering just such an "exoplanet," as planets outside our solar system are known.

A NASA illustration of the Kepler Space Telescope, the findings from which suggest there may be as many as 40 billion Earth-like planets in the universe. /NASA via AP

For a Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist, he has a winningly straightforward view of the task at hand.

"Life is nothing else than a chemistry process," he tells

The Answers Project

. "There's no magic, there's no 'something special' about life.

"It's a chemistry process that has become its own master – life managed to make its own chemistry and to evolve. Chemistry is the same everywhere in the universe and if the right conditions are met, you create life."

Could you have some kind of species that is able to reach a level that can travel to space? That's a very open question

- Didier Queloz, Cambridge University

Examining meteors and asteroids suggests the elements considered necessary for life –carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, silicon, sulphur, phosphorous, copper and iron, for example – seem to be present throughout the universe, configured into recognizable vital structures like organic molecules, sugars and amino acids. The question might therefore be one of evolution, says Queloz.

"The life mechanism is as well developed in blue algae as it is in my body – there is no difference," he says. "The concept of having machinery which is alive and evolving didn't wait for us. Could you have some kind of species that is able to reach a level that can travel to space? That's a very open question at this point."

The Fermi paradox and the Drake equation

It's a question that raises an objection memorably summarized by the Fermi paradox: If alien life is so likely, where's the evidence?

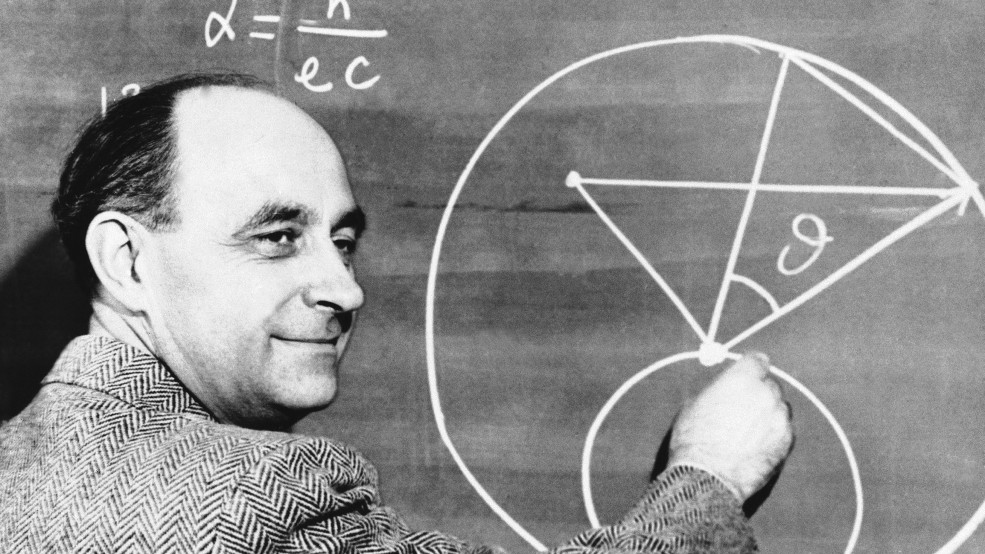

Enrico Fermi was a fascinating character. Equally at home in theoretical physics and experimental physics, he left his native Italy in 1938 to protect his Jewish wife, moving to the U.S. and becoming a leading light in the Manhattan Project which led to the development of the nuclear bomb.

The brilliant physicist Enrico Fermi came up with all sorts of answers – and a very important question. /AP

His relevance to the question of extraterrestrial life was his Occam's Razor-style summary of the paradox. If there are billions of planets suitable for the evolution of intelligent life, and indeed many of them are billions of years older than ours, why haven't they popped by to say hello? As Fermi is said to have asked during a lunchtime discussion, "Where is everybody?"

On this point, the science is more theoretical than evidential – and the theories can be disputed. In 2018, a paper called

Dissolving the Fermi Paradox

seriously questioned the assumed high probability of life elsewhere, particularly attacking the Drake equation habitually used to estimate the chances of other civilizations.

The problem is 'reasonable probability.' Where does that come from?

- Anders Sandberg, Oxford University

Oxford University professor Anders Sandberg co-authored the paper, and he explains the idea to CGTN.

"We noticed that many people, when they reasoned about it, do something like this: 'There are many places in the universe and a lot of time where life and intelligence could emerge. Multiply that with some reasonable probability and you ought to get a lot of intelligent life.'

"The problem in that sentence is 'reasonable probability.' Where does that come from? And people bring up the Drake equation and then they put in numbers and admit they are guesses and then they get a number out of it, which is also a guess, so they admit that too.

"When I'm guessing at how many inhabitants there are in London, I should be giving a range instead of just saying a number and saying 'I'm kind of uncertain about this.'"

Trapped in time and space

Humans have spent decades sending radio waves into space, and more recently scanning for responses –including using well-meaning needle-in-haystack ventures like

, which used the spare capacity of home computers to comb through radio telescope data for signs of messaging.

SETI@Home was paused last year to allow scientists to analyze the results of 21 years' scanning. But even those results were only fractional samples. Searching for life elsewhere is difficult when the universe is mind-bogglingly large, with potentially life-hosting planets dotted only sporadically throughout those interstellar reaches: If we wish to hear from alien life, where do we point our ears?

The Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico spent decades scanning the skies for extraterrestrial messages – but it was decommissioned in 2020. /Chris Hawley/AP Photo

It's a question that worries Janna Levin, a Columbia University professor and author of several popular science books. Noting that humans have only been sending up signals for less than 100 years, she points out that "The distance light has had to travel in 100 years is nothing, nothing compared to the scale of the galaxy. The galaxy is over 100,000 light years across, and that's just our galaxy.

"Now, there are planets in that small region, but you've barely begun to communicate with your neighbors at that point. And so to really imagine a species that's lived long enough to send a signal that reaches the other side of the galaxy, that species would have been able to harness technology hundreds of thousands of years ago... and then you have to wait for the signal to come back."

Have more modest ambitions. See if there are microscopic forms that are metabolizing

- Janna Levin, Columbia University

So besides the brain-crushingly enormous distances between planets, there is another dimension which may be working against us: Time. Is our relatively fleeting spell as an interplanetary exploratory species coinciding with anyone else's? Levin worries about that, too.

"There is this haunting feeling when you look out into the Milky Way that even if there is life out there somewhere, the likelihood that it happens to overlap technologically with ours and is also simultaneously near enough to communicate with us – that starts to feel epically unlikely," she says.

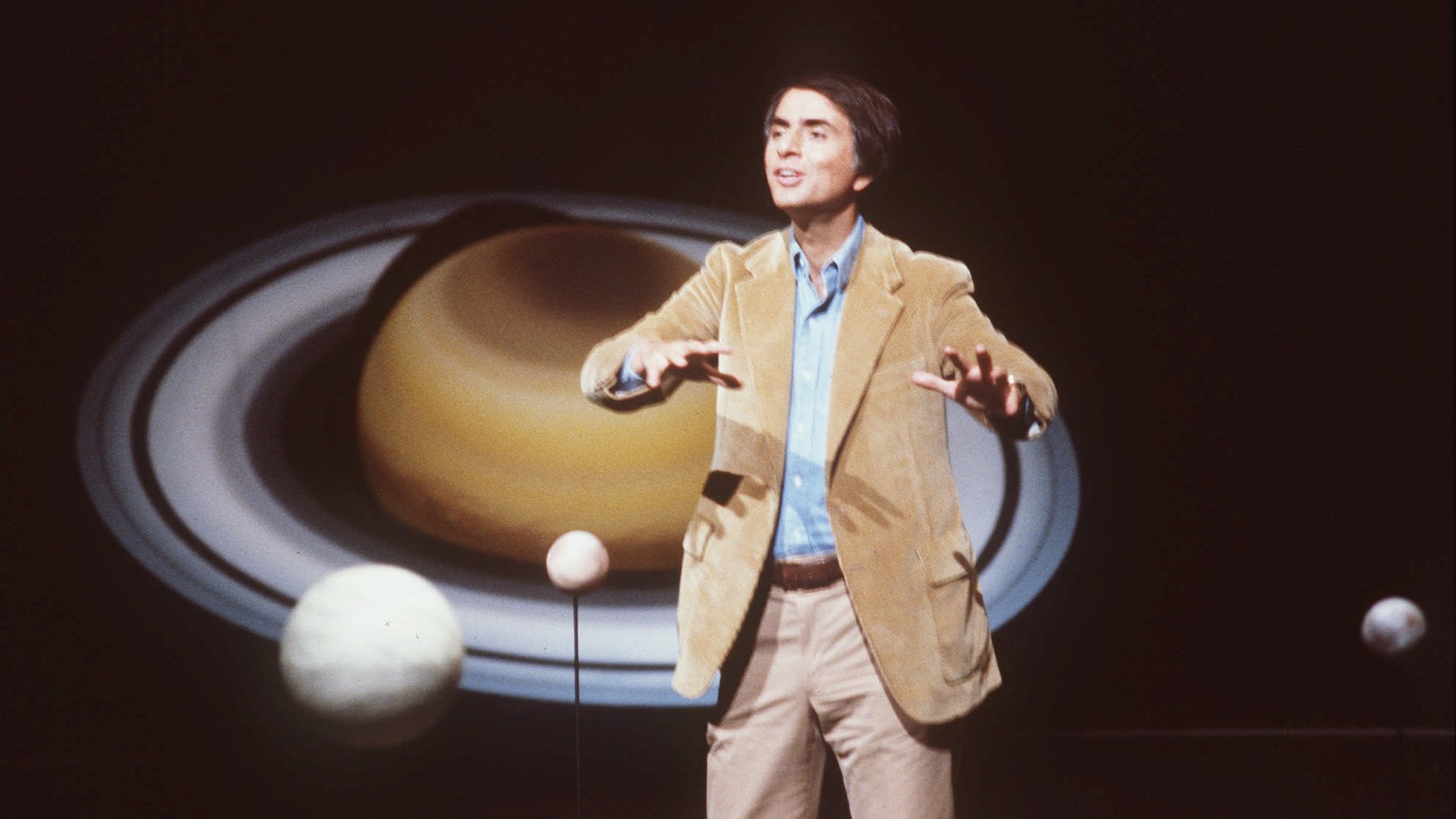

Carl Sagan did much to popularize the search for extraterrestrial life, but as a scientist he insisted that 'extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.' /Castaneda/AP Photo

Levin suggests we reset our expectations. She points out that in terms of geological time, let alone cosmological, "We're a blip on our own planet," yet in our search for other life we are "asking for this alignment with a technologically sophisticated society."

"Have more modest ambitions," she suggests. "Just try to see if there are microscopic forms that are metabolizing –that's what we really mean by life: It eats things and it metabolizes things.

"That's where the hope is, to look for signatures in the atmospheres of some kind of metabolic processes that we might consider to be life forms."

Little green men

While Levin and other scientists might be happy to find an active bacterium, the popular imagination still seems to be set on little green men in flying saucers. Every year there are thousands of sightings of potential UFOs, fueling the fascination (and indeed conspiracy theories) without satisfying the scientific community.

"The evidence has continued to grow and the number of sightings continues to grow," says Arizona University astronomy professor Chris Impey, "but the evidence has never met the bar that scientists would place on such an extraordinary hypothesis of alien visitation."

Impey cites Carl Sagan, the much-loved American astrophysicist whose tireless work in popularizing the search for extraterrestrial life never included suspending his scientific insistence on proof.

There are sightings of aircraft moving in very unconventional, almost unphysical ways. So I would keep an open mind

- Chris Impey, Arizona University

"There's a gold standard of evidence," says Impey. "Carl Sagan put it as 'extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence' – if you're going to say that aliens have traveled across the galaxy and visited Earth, you need something a little more than one eyewitness account."

Impey retains an open mind while noting the widely-varying quality of evidence. "Most of it is easy to dismiss – the conspiracy theories and abduction reports are almost amusing," he says. "But there's a little persistent residue of evidence that emerges from military sources and then gets declassified.

"For example, there are sightings of aircraft moving in very unconventional, almost unphysical ways – a little residue of evidence that's very provocative and it has some validity because of the source. So I would keep an open mind as a scientist on the possibility that there's something that truly does need to be explained."

Nasty, brutish and short

It is no coincidence that most alien contact in science fiction creates some sort of violent confrontation, and frankly the fault doesn't always lie with the space invaders.

English philosopher Thomas Hobbes called the life of humans "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short," and given humankind's potential to wipe itself out –through warfare, environmental catastrophe or any other means – some scientists fear we may no longer be at home when the neighbors come calling.

Dolphins don't seem interested in interstellar communication, but they seem happy enough. Is expansionism incompatible with longevity? /Petko Momchilov/AP Photo

"I do have a little bit of the pessimist's dystopian fear that longevity doesn't come hand-in-hand with intellectual complexity," says Janna Levin. "Maybe the longer-lived species are simpler and less aggressive with their environments."

Levin hypothesizes that perhaps species like ours, which evolve to manipulate their environment, "are inherently destructive and aren't capable of prolonging their lives long enough to be able to communicate with each other and other civilizations."

Two possibilities exist: Either we are alone in the universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying

- Arthur C Clarke, sci-fi writer

Wondering whether evolutionary 'success' can be measured by expansionism, she compares humans to dolphins – "A very happy, very successful species, has no intention to send messages out into space and isn't trying to receive any. Maybe those are the most successful kinds of animals that emerge on other planets as well."

Pioneering sci-fi writer Arthur C Clarke wrote "Two possibilities exist: Either we are alone in the universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying" – but Levin refuses to feel hopeless or fearful.

"Imagine you are shipwrecked on an island," she says. "There would be a sense in which you felt alone, but you would also know that you were not literally alone. That's how I see life around exoplanets.

"I imagine there is life out there – I can't believe that there isn't, it would be absurd, nature is just too inventive. The question is, is are we all marooned on our islands and throwing messages in a bottle out into space? I hope more just to find out 'Yes, there are other life forms out there' than that I will receive a message in a bottle."

For much more on the topic –including Anders Sandberg on how to fix Fermi's paradox –click on the podcast at the top of the page.

**Previously on **

The Answers Project

**: **Will soldiers become obsolete?

** • **When should children start school?

** •** How much is a life worth?

** •** Should exporting waste be banned?

** • **Why don't we have a global currency?

Click here to subscribe to The Answers Project Podcast

简体中文

简体中文