Swedes enjoy drinks with friends in crowded cafes and restaurants. /Andres Kudacki/AP Photo

Crowds gather in Sweden's parks to enjoy the sun or sit by the water, while friends enjoy drinks in Stockholm's restaurants and bars.

Many people across Europe could be excused for thinking this is just a description of life before the coronavirus pandemic hit and lockdowns implemented across the world confined billions to their homes.

But they would also be mistaken, as this is the scene in Sweden today and it looks very different from neighboring countries on the continent.

The Swedish government's coronavirus containment strategy is considered an outlier in Europe and has been criticized by some in the country for being too relaxed and not robust enough to stop the spread of the virus.

"We are now estimating around 250,000 infected individuals within Stockholm with a doubling rate of approximately a week now, at the end of next week we are expecting half a million," professor of microbial pathogenesis, Cecilia Söderberg-Nauclér, told CGTN Europe's

The Agenda

program.

"So we are concerned it's going too fast, that the mitigation strategies that have been implemented for the country are not enough to flatten the curve enough in order to meet these demands," Nauclér added.

06:36

Lockdown measures

Sweden is one of a few countries that has not enforced strict lockdown measures, opting to keep lower schools, restaurants, businesses and public places open, while only banning gatherings of more than 50 people and barring visits to nursing homes.

This is in contrast to other countries in Europe that have implemented complete lockdowns, shutting schools and public places, severely limiting movement and banning gatherings to a minimum number of people, in some cases as little as two.

Amid increasing questions over the country's strategy, health and social affairs minister, Lena Hallengren, said in a press conference last week she doesn't believe the country to be an outlier. "I have noticed there is at times a belief that Sweden has a radically different approach to the virus from other countries, I do not share that belief," Hallengren said.

"Sweden's measures only differ from other countries in two major regards – we're not shutting down schools for younger children or children's care facilities, and we have no regulation that forces citizens to remain in their homes," she argued.

Sweden's foreign minister, Ann Linde, also defended the country's approach, saying: "It is a myth that life goes on as normal in Sweden."

She added: "Many people stay at home and have stopped traveling, many businesses are collapsing, unemployment is expected to rise dramatically."

Figures have shown that currently around 50 percent of the Swedish workforce is working from home. The capital Stockholm is also around 70 percent less busy, as public transport use has fallen by 50 percent.

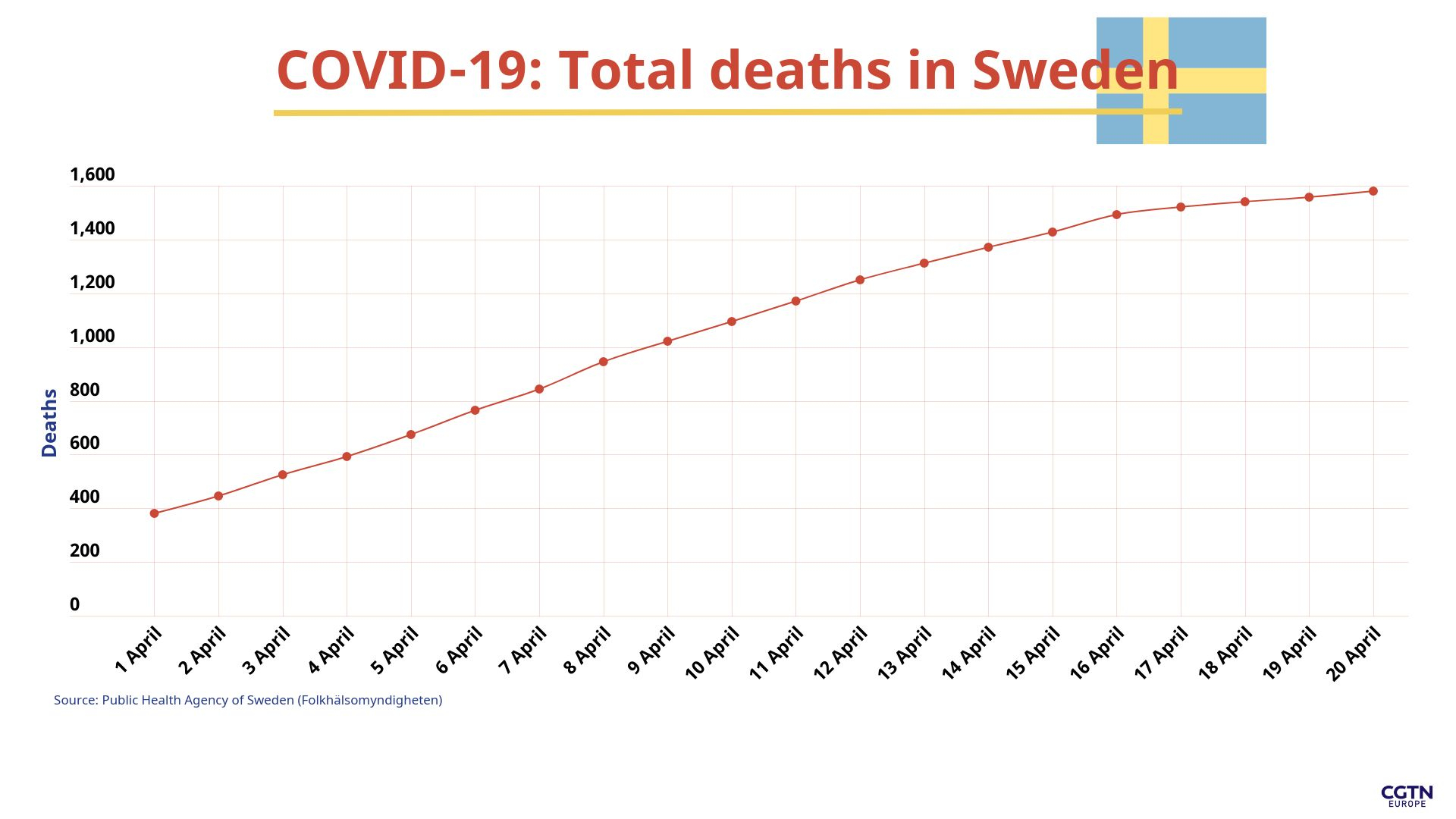

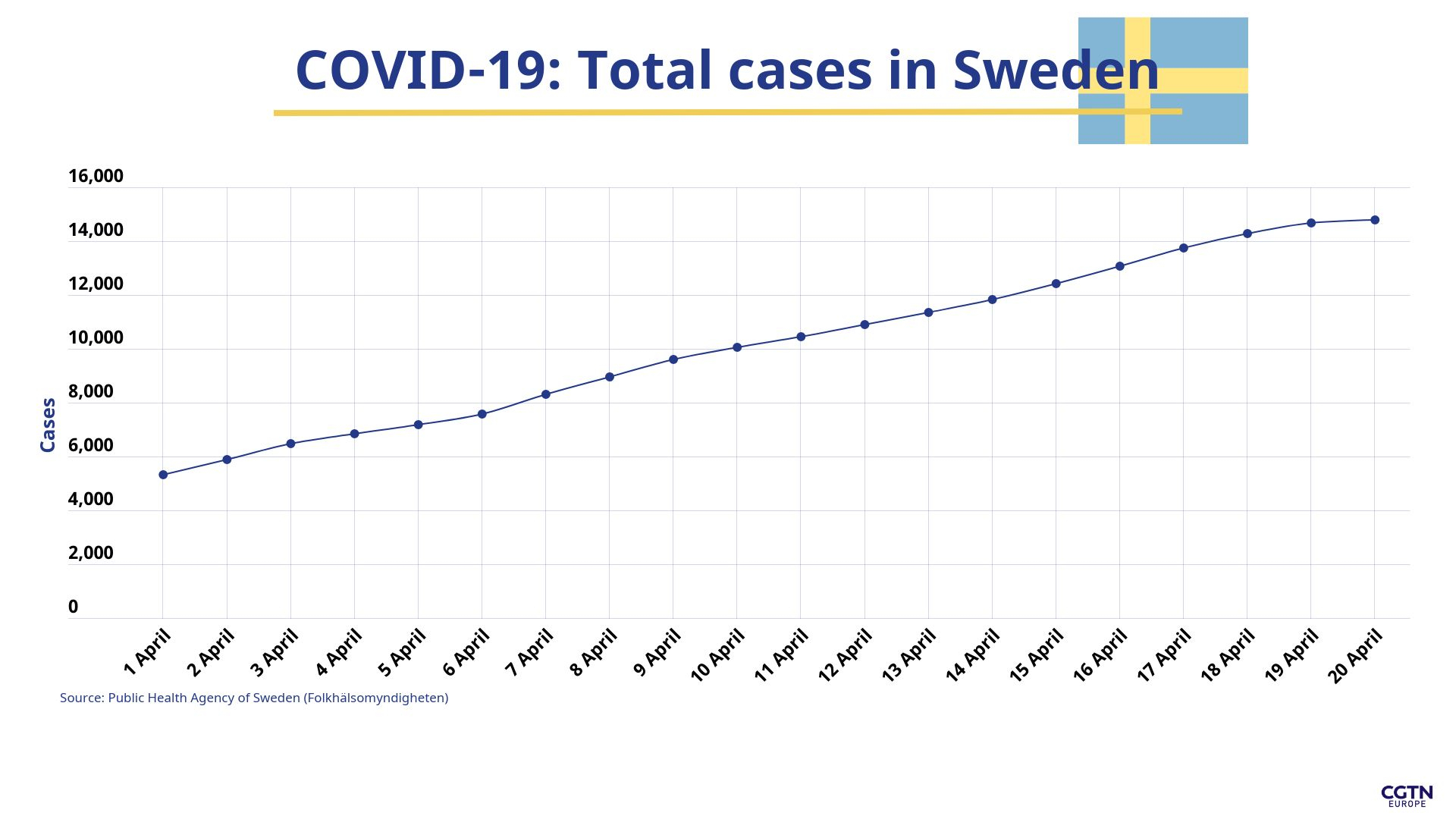

But with the number of coronavirus cases nearing the 15,000 mark and deaths already topping 1,500 in the country, which has a population of 10 million, scientists are warning this number will increase drastically without stricter measures.

Hairdressers and salons are among the businesses still open in Sweden, that are closed elsewhere in Europe. /Andres Kudacki/AP Photo

'Risky strategy'

Many scientists agree it is too early to know what approach is best to contain the spread of COVID-19, as the virus is yet to be completely understood.

However, the Karolina Institute's Söderberg-Nauclér said that by looking at other countries, the time it takes their mitigation strategies to take effect and turn around the infection rate is two-and-a-half to three weeks.

"We have a transmission that is so fast now in Stockholm that we can't prevent that. We can only see when it has happened and by then it's too late," Nauclér said.

"Therefore, we think [we] should be taking that principle of precaution and trying to be safe rather than sorry and not to go for a risky strategy that is untested because no one has really done this," she added.

Nauclér was one of around 2,300 researchers and academics who demanded stricter regulations and measures to protect the healthcare system in an open letter to the Swedish government late last month.

More recently, a group of 22 Swedish doctors, virologists and researchers upped their criticism of the Public Health Agency in an opinion piece published by the national

Dagens Nyheter

newspaper on 14 April.

"The approach must be changed radically and quickly," the group wrote. "As the virus spreads, it is necessary to increase social distance. Close schools and restaurants. Everyone who works with the elderly must wear adequate protective equipment. Quarantine the whole family if one member is ill or tests positive. Elected representatives must intervene, there is no other choice," they added.

The group also said the agency claimed on four different occasions that the spread of infection had leveled out, despite evidence this was untrue. They pointed out the slowdown in infections and deaths in Finland, which implemented much more restrictive measures as early as the second week of March.

"So in Sweden, more than 10 times as many people are dying than in our neighboring country Finland," they wrote

The Swedish Public Health Agency hit back at the criticism, calling the claims inaccurate. In a press conference, the country's chief epidemiologist, Anders Tegnell, strongly rejected the accusations and disputed the figures they presented.

Nursing homes in Sweden struggle as many say the elderly are paying the price for the country's coronavirus strategy. /David Keyton/AP Photo

Getting more people immune

Tegnell, considered the architect behind the country's containment strategy, described the Swedish approach as an attempt to ensure "a slow spread of infection and that the health services are not overwhelmed," and argued that immunity for part of the population was the most important goal.

Speaking to local media on Sunday, Tegnell defended the country's strategy, saying that immunity among part of the population of Stockholm could be achieved as early as next month.

"According to our modelers [at the Public Health Agency], we are starting to see so many immune people in the population in Stockholm that it is starting to have an effect on the spread of the infection," he told reporters.

"Our models point to some time in May," he predicted, adding that the reality is of course yet to be seen, as mathematical models are only as good as the data put in.

However, Tegnell had previously denied the country's strategy was to build rapid "herd immunity" to the virus, a strategy considered by the UK and the Netherlands at the start of the pandemic before increased death rates made them change course.

Scientists critical of this approach say it is untested, unlike strict lockdown measures that have been tested in other countries to gain control of the situation.

"No one has turned around [the infection rate] on a herd immunity situation. And even though that's not explicitly said by our government, because we are expected to infect the population at a slow pace – that, we don't know either how that will work," Nauclér said.

"So we're just fearing that in a few weeks' time, we are going to lose control over this in Stockholm. And that will be very sad. It would have been better to react earlier and tried to keep this under control," she added, a view shared by others in the country.

Although Tegnell last week said: "The number of new people in intensive care is still on about the same level as before, many of the figures are staying on the same level as they have done for the last week or so," scientists project increasing numbers over the next few weeks.

"At the current time, it looks like from the symptomatic cases in Stockholm, it's actually over one percent death rate at the current time, so that means that if one million are infected in a month from now, that's going to regenerate 10,000 dead in Stockholm a month later. And that is only for Stockholm," Nauclér said.

"So the rest of the country, if we're going for herd immunity strategy, we will infect between 40 percent, 60 percent or 80 percent of the population," Nauclér projected.

The chief epidemiologist continuously rejected the criticisms aimed at the strategy, and disputed figures brought forward by researchers showing the country's death rate per population to be much higher than that of its Nordic neighbors.

Tegnell previously said Sweden and its neighbours were on "different places on the curve," and that the country had "unfortunately had a large spread of contagion in care homes for the elderly, something you have not seen in the other Nordic countries."

With anger mounting in the country in recent weeks that the elderly were paying the price for the controversial strategy as deaths continue to rise, Tegnell admitted last week that this was a problem.

"What has not worked very well is our aim to protect the elderly," Tegnell told reporters. "Unfortunately we had quite a lot of people in elderly homes who got infected and died, and that's very unfortunate and something we're working very hard on trying to rectify," he added.

As one of its new measures, the government said on Friday that testing for COVID-19 would be dramatically increased and rolled out over the next weeks, primarily targeting people with severe symptoms as well as key workers, to allow them to return to work faster after showing symptoms.

"We are talking about testing and analysis capacity of 50,000, perhaps as many as 100,000, a week," health minister Hallengren told a press conference. So far, almost 75,000 people have been tested in Sweden, Hallengren said.

Still, scientists maintain the issue is that people are getting infected in the first place due to relaxed social-distancing rules and limited lockdown measures.

"But the risk assessment is still to say, do we dare to risk a strategy where we are overloading the health care system?" Nauclér said.

Tegnell argued it's important to have a policy that can be sustained over a longer period of time, as sooner or later people will become restless and go out anyway.

"This level of measures that we have in Sweden — there is no problem for us to keep it running for months," Tegnell told Reuters. "Closing schools, more stringent measures like that, closing borders — you cannot do that for months or years ahead. But what we are doing in Sweden we can continue doing for a long time, and I think that's going to prove to be very important in the long run," he added.

Through these measures, Sweden hopes that, while in the short term infection and death rates will be higher, for the long term, the effects will minimize drastically and avoid risking the reinfection that other countries may face once lockdown measures are lifted.

But as no one has the power to look into the post-coronavirus future, the outcome of Sweden's controversial strategy is yet to be seen, though many say the current losses are not worth the risk.

简体中文

简体中文