Amid the outbreak of COVID-19, Muslims gather for Friday prayer on a road in Peshawar, Pakistan, March 20, 2020. /Reuters

What is more important: saving one's life or fulfilling religious obligations? Isn't saving one's life a religious obligation as well? How to offer congregational prayers and still be safe from COVID-19? This is the puzzle the Muslims in Pakistan are trying to solve as they brace for Ramadan, the holy month of fasting, amid the outbreak of a disease that doesn't discriminate between believers and non-believers.

While the holiest of all Muslim places, the Holy Kaaba in Saudi Arabia, continues to restrict mass gatherings over fears surrounding COVID-19 – prayers attended only by clerics and maintenance staff – the Pakistani government has come to conclude that congregational prayers in the month of Ramadan might just be fine if certain standard operating procedures (SOPs), such as social distancing, are followed.

However, this seems a bit paradoxical because the very spirit of "congregation" runs contrary to what "social distancing" entails. Mosques not only serve as places of worship but community centers for socialization. And the congregation is a way to show unity and strength, which according to many Islamic schools of thought, is reflected by the way worshipers assemble themselves in a mosque during a prayer: shoulder-to-shoulder, with little or no distance in between.

Given this situation, one begs to question: Would standing six-foot apart satisfy those who believe in "proximity"? How can one socialize and practice social distancing at the same time? After all, if the objective is just to pray and not socialize, one could just pray at home. But things get tricky when you talk about the deeply religious country of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the month of Ramadan when the emotions run high.

It remains to be seen how the worshipers respond to the government's SOPs, but first, let's see how we got here in the first place.

Friday prayers along the roadside in Islamabad. /AFP

Close the mosques, lives are more important

The federal and provincial governments of Pakistan had put a limit on congregational prayers in mosques in the last week of March, with the governments allowing no more than five people to offer prayers in mosques. The ones allowed were mainly the

imam

(prayer leader),the muezzin

(person who makes the prayer call),khatib

(person who delivers the sermon) and caretaker of the mosque, basically leaving no room for worshipers from the outside to offer their prayers inside.

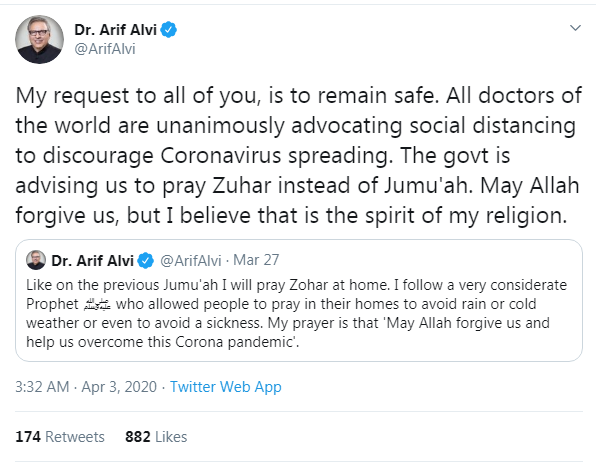

More so, Pakistani President Arif Alvi even sought "guidance" from Egypt's Al-Azhar University, a highly revered Islamic institution, which issued a

fatwa

(edict) permitting the suspension of Friday prayers to control the spread of the deadly coronavirus.

A screenshot of the Twitter page of Pakistani President Arif Alvi, who is advocating offering Friday's afternoon prayer at home. /@ArifAlvi

Open the mosques but follow rules

However, the aforementioned decision met a fiery response from clerics around the country, with many people flouting the ban and sneaking in the mosques to offer congregational prayers.

As it escalated and in light of the approaching month of fasting when the Muslim-majority population of the country holds special gatherings, President Alvi held a meeting with some prominent clerics and announced on April 18 that congregational prayers would be allowed during Ramadan only if certain rules listed in a 20-point action plan are followed.

Per the plan, everyone would wear masks; social distancing would be observed; congregational rows would be formed with a six-foot distance between worshipers; people would refrain from discussions; handshakes or hugs would not be allowed; elderly and sick would not come to mosques; there would be no carpets in mosques and people would bring their own prayer mats; mosque floors and prayer mats would be washed with chlorine; mosques with compounds would hold prayers outside; ablution should be performed at home;

taraweeh

(a special conditional prayer offered only in Ramadan) would be held only inside mosques and not on roads; people should perform aitekaf

(a 10-day conditional worship usually done at mosques) at home; mosques would not serve sehri

(meal before fasting) and iftaari

(meal to break the fast); committees would be formed to monitor compliance; mosque administrations would cooperate with the local police, and the two shall ensure compliance; and government shall review this policy if measures are not being followed or there is an exponential rise in COVID-19 cases.

A screenshot of the Twitter page of President Arif Alvi, who is admiring distancing observed during prayer. /@ArifAlvi

Seeming concerned about how things might turn out, the president stressed on several occasions after last week's meeting that now when a unanimous agreement has been reached in consultation with the religious scholars over how the congregations would take place, it would be tantamount to "sinning" if someone flouts the rules. He also highlighted the last point of the plan that the government has the authority to revise the rules in case of a rise in infections or if the rules are not observed. He urged the nation to have some discipline in these troubling times.

However, things are easier said than done, and discipline has never been a forte of the extremely diverse Pakistani nation. Who is to blame if the congregations lead to a further spike in COVID-19 cases – the government who allowed congregations or a vast majority of people who just wouldn't do without them? Conversely, who is to bear the "sin" if the congregations are suspended – people who didn't raise their voice for their religious beliefs or the government who chose to rather save lives?

Apparently, health, economic and social impacts of the pandemic are not the only adversities Pakistan faces, but also something that one may call the "religious impacts" of COVID-19.

Doctors have something to say

A police officer detains a doctor protesting against the lack of protective gear for medical staff who are treating COVID-19 patients in Quetta, Pakistan, April 6, 2020. /Reuters

In the meanwhile, doctors, many of whom have already been protesting over the lack of medical supplies, are not at all happy with the government's decision to open the mosques during these challenging times – and one can't blame them, as they are the ones essentially fighting the pandemic on the front line.

"This fight is between the coronavirus and doctors, so please listen to us ... You (government and scholars) have held a meeting without including any technical person. You have drafted 20 SOPs. Please tell me, will these SOPs be followed in Pakistan's mosques?" a leading Pakistani newspaper quoted Pakistan Medical Association Secretary General Dr. Qaiser Sajjad as saying on April 22 during a press conference at the Karachi Press Club, all the while lamenting that the lockdown in the southern Sindh Province had "become a joke just like in the rest of the country."

"I have to say, with all due respect, that our government has made a very wrong decision and our

ulema

(clerics) have demonstrated extreme insensitivity [akin to] playing with human lives."

Figure talk

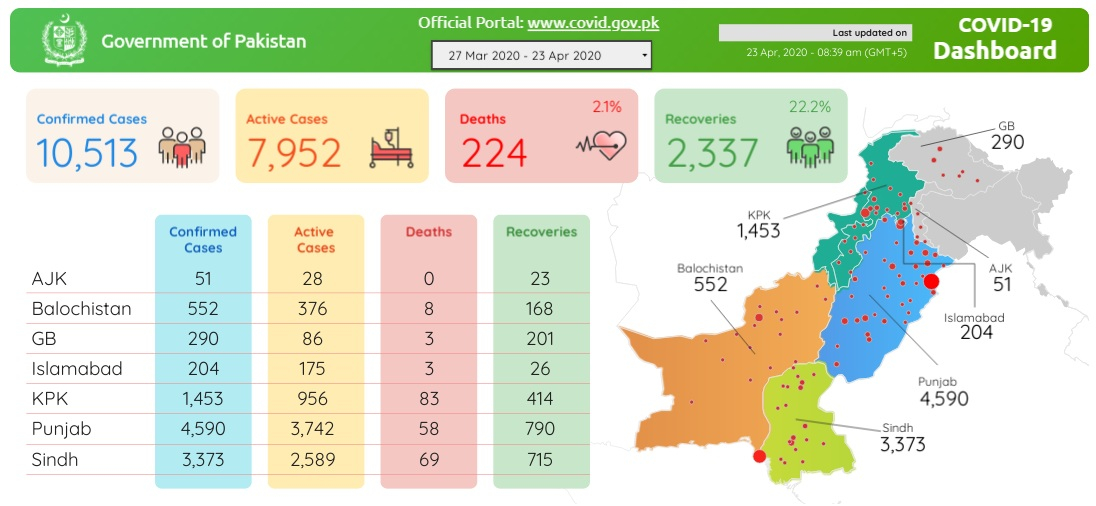

A screenshot from covid.gov.pk launched by Pakistan's Ministry of National Health Services Regulations & Coordination.

According to official statistics published on covid.gov.pk, the number of COVID-19 cases in Pakistan surged from 7,993 on April 18 – when the congregational prayers were officially allowed – to 10,513 on April 22. The number of daily cases, which had largely remained around 400-500, touched 796 on April 20, the highest increase ever.

One good news, however, that came on April 22 is that Prime Minister Imran Khan, who had to undergo the coronavirus test after he came in contact with a patient a few days ago, tested negative, Special Assistant to the PM on Information and Broadcasting Dr. Firdous Ashiq Awan tweeted.

While the Pakistani government has been trying hard to keep the pandemic in check, the Pakistani people walk on thin ice with the arrival of Ramadan as the SOPs for congregational prayers are ready to be put to the test by the worshipers who, geared with the power of belief and that of a mask, make their way to the mosques. These are testing times indeed – the test of the government and that of people's faith.

Beijing

Hong Kong

Tokyo

Istanbul

New Delhi

Singapore

Damascus

Baghdad

Islamabad

Seoul

Brussel

Moscow

Canberra

Cairo

Nairobi

Johannesburg

Washington,D.C.

Los Angeles

Rio de janeiro

3884km

简体中文

简体中文