After leaving his job as chief creative officer at Microsoft’s Xbox, Elan Lee started tinkering with a new game. It would have explosions, laser beams and nightmarish creatures. But unlike the video games he shepherded through production at Xbox, this one wouldn’t require hordes of developers or years to finish.

All it took to make Exploding Kittens was paper, cardboard and an idea.

“Games are back,” says Lee, whose card game has sold 2.5 million copies since its release a year ago. “I’ve been into games my whole life, and it’s so exciting to see that there’s a return.”

While video games hog the limelight, board and card games – known as tabletop games – are enjoying a quiet resurgence. Many are turning to these retro pleasures as a respite from the computers, gaming consoles and mobile devices thought to have rendered board games obsolete.

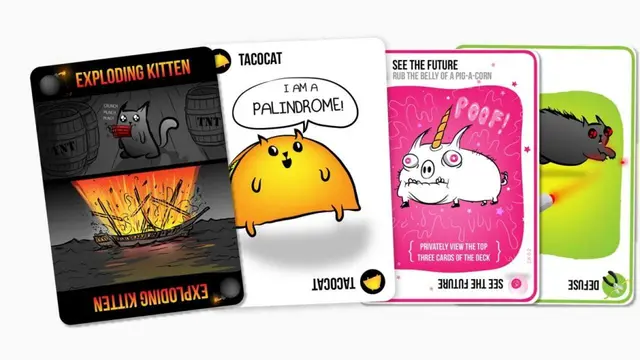

Introduction to Exploding Kittens

Games and puzzles were the fastest-growing toy category last year, climbing 11 per cent to US$1.6 billion, according to the NPD Group. That streak continued into the first four months of 2016, with game sales jumping 24 per cent – four times the pace of the overall industry.

They remain small compared with the US video game industry, which raked in US$23.5 billion in sales in 2015. But giant toy makers Hasbro and Mattel have seen growth in games and puzzles even as other segments stumbled. And smaller game designers have found creative freedom producing off-line entertainment aimed at adults - and a surprisingly simple business model that often bypasses traditional retailers.

Board and card games are especially appealing to millennials, analysts say, because they crave face-to-face intimacy in an age when social interactions are often defined by disappearing Snapchats and tweets.

“The social nature of games is very attractive to people, especially younger people,” says Jason Moser, a toy analyst at the Motley Fool multimedia financial services company. “Games are a way to tap into that feeling that perhaps has been lost for a while because of the quick movement to mobile.”

Lee, a video game designer for 17 years, knows firsthand both the lure and the loneliness of digital games. When he left Xbox, he yearned to make something more social.

“I just had an overwhelming feeling the games I had been building for such a long time were very isolating,” Lee says. “They might be playing multi-player games, but they are sitting alone and staring at a screen.”

His card game was initially called Bomb Squad before Lee showed an early version to Matthew Inman, a friend and the creator of the popular comics website the Oatmeal. Inman loved the concept but suggested a twist: instead of bombs, the losing cards should show adorable felines stuck in explosive scenarios (chewing a mouthful of TNT or dancing on a nuclear missile launch pad).

Last year, the pair decided to raise US$10,000 via the crowdfunding site Kickstarter – enough money to print 500 packs. The game ended up receiving nearly US$9 million, attracting the most backers in Kickstarter history.

A sample round of Exploding Kittens

The costs of creating a board game are relatively low compared with a video game, which can require millions in the development phase. However, that calculus flips after the game is created. Video games are mostly downloaded nowadays, so there is no added manufacturing cost. Board games – especially those that come with figurines, spinners or other parts – can be costly to produce.

Game developers say a tabletop game typically nets between 30 per cent and 50 per cent profit. That’s compared with video games, which are 100 per cent profit – after recouping development costs.

Kickstarter has emerged as a proving ground for tech-free games – and a way to eliminate upfront costs as backers pay in advance for copies. Games, of the off-line variety, have scored nearly US$300 million in funding since the site launched in 2009, the company says.

Luke Crane, head of games at Kickstarter, says there’s been “a huge leap” in tabletop game design in recent years.

“Games are getting better – better design and components, with more thought,” Crane says. “And you have a hungry, hungry community with a lot of people with disposable income willing to support these designers.”

Before the rise of television, board games were once a popular national pastime. But as family game nights became TV time on the couch, few new titles enjoyed mainstream success.

Actor Wil Wheaton, the host of TableTop, a popular web series about games, said the resurgence of board and card games started in the 1990s with the trading card gameMagic: The Gathering. Many who grew up playing Magic are now enthusiastic consumers of other games.

“That brought gamers into the hobby who would have been really turned off by some of the byzantine war games that sort of dominated that space up to that point,” he says.

Imports from Europe, where designers had invented games of increasing complexity, also gained a following in the US Strategic games such as Settlers of Catan andTicket to Ride enticed players with an appetite for nuance instead of luck.

Board and card games have evolved from an “extremely nerdy, weird niche” into a mainstream hobby, says Max Temkin, 29, co-creator of Cards Against Humanity – the self-described game for horrible people.

With so much grass-roots interest, companies with no background in games have jumped in.

Rooster Teeth, an online entertainment company with offices in Los Angeles, created a card game this year inspired by their popular web series “A Million Dollars, But … .” In short, the game asks players what they’d be willing to endure in exchange for a boatload of cash.

(SCMP)

简体中文

简体中文