At the end of 2019, there were almost 80 million people forcibly displaced across the world, fleeing war, poverty, conflict and persecution, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

That's equal to roughly one percent of the global population – a number that might sound small, but "70 million is the size of a big country, it's a lot of people," said UN High Commissioner for Refugees Filippo Grandi.

"These are people who have no more the protection of their own country, so they need international protection. It's quite a big number, I would say," he told CGTN.

04:21

When we spoke to Grandi last year, the issues facing refugees and migrants across the world were many and urgent.

"There's insufficient action to address the causes of why these people are moving, and that's a very wide range of issues. There's insufficient peace-making in the world – that's why wars continue forever or are never really resolved.

"Then there's very unstrategic use of development assistance to address inequality, poverty, the consequence of climate change."

How have things changed?

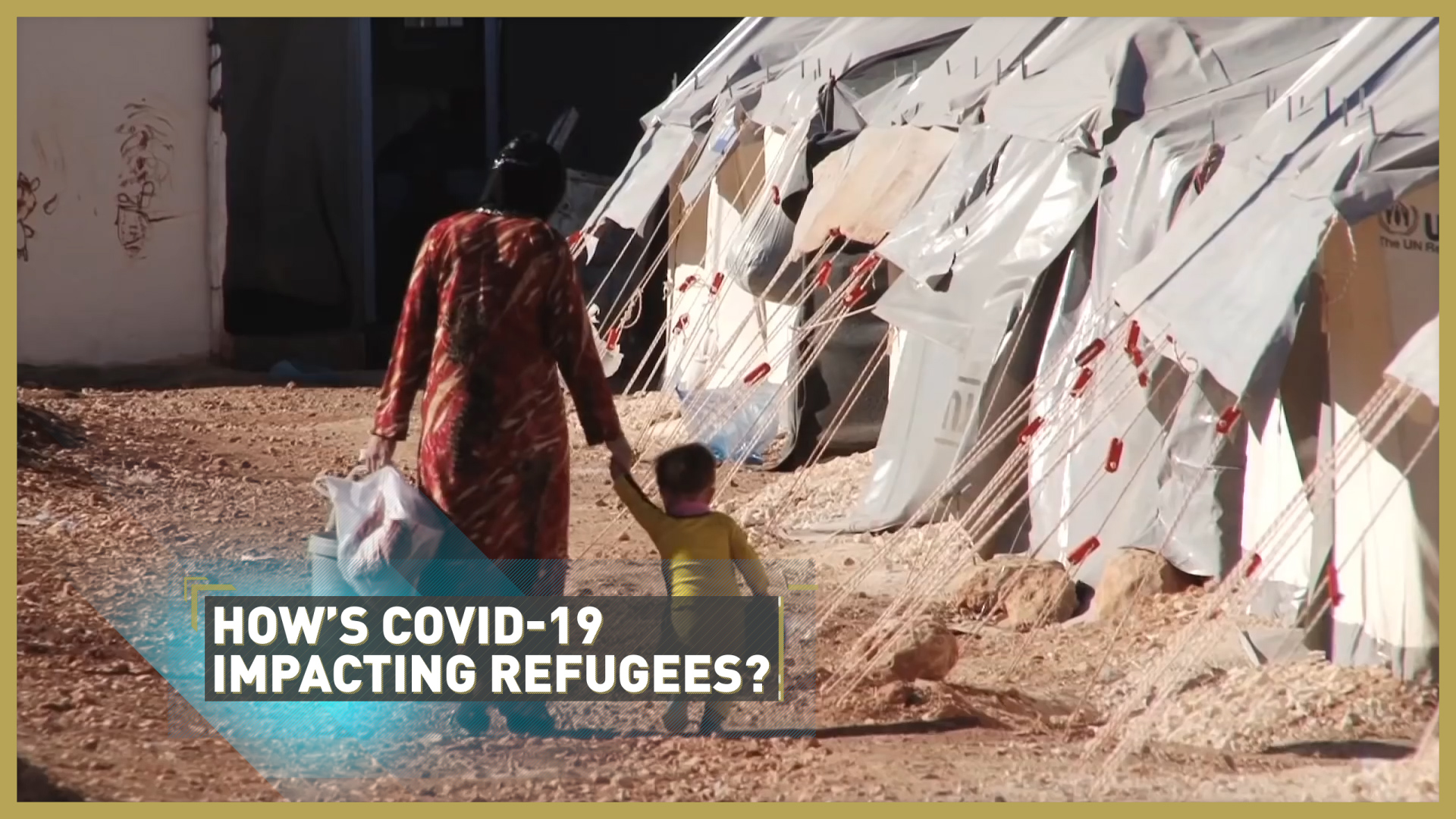

One year later, the problems to address are just as many – with one additional, unexpected complication. In the midst of a situation that could hardly be any worse for many people, a global health emergency brought more chaos.

The COVID-19 pandemic has abruptly disrupted the life of millions of refugees – and even the life of Grandi, who just announced he has tested positive for the coronavirus.

A woman holds her child as refugees from the islands of Lesbos, Chios, Samos, Kos and Leros wait to board buses after disembarking at the port of Lavrio, 70 km southeast of Athens, prior to be transferred to camps in mainland Greece /Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP

As Grandi entered isolation in his home, we talked to Assistant High Commissioner for Protection at UNHCR, Gillian Triggs, about how refugees have been affected by the pandemic.

"They really have suffered immensely, partly because of closed borders and denial of access to asylum processes – that's perhaps an obvious one," she says.

"But less obvious is that they are particularly affected by social and economic consequences. So the lockdown has meant, in the informal economy, loss of jobs, particularly for refugees and displaced people.

"Their children are out of school. They've suffered gender-based violence as families fracture. So the consequences are really profound. And we expect them to last for a very long time."

An Iraqi mother with her child at the port of Lavrio, Greece. /Louisa Gouliamaki/AFP

On the issue of countries closing their borders to refugees and migrants amid coronavirus fears, Triggs urges nations to acknowledge their fundamental obligations to offer protection and shelter to refugees seeking asylum – even under the restrictions caused by the pandemic.

"More than half of the countries in the world have shown that you can keep your opportunities open to claim asylum.

"So, for example, remote capacities to receive asylum applications, quarantine, all sorts of identity checks and so on, can be done in ways that are humane and keep that space open for those who are claiming asylum from persecution."

Though the worst of the European refugee crisis is in the past and the number of refugees entering the EU has decreased, the fire that burnt the Greek refugee camp of Moria to ashes this September was a dark reminder of the tragic reality of thousands of people who, to this day, remain in limbo, living in precarious conditions made even worse by the pandemic.

The newly approved EU Commission's pact on asylum and migration, calling for a mandatory system across the bloc to manage migrations and for "fair sharing of responsibility and solidarity between member states while providing certainty for individual applicants," in the words of German Chancellor Angela Merkel, has once again sparked controversy among the EU27, and deepened internal divisions.

"There are divisions, there's no doubt about that," says Triggs. "But of course, we're at an early stage. The pact has only been available to member states for the last few days. The United Nations Refugee Agency that I represent, we are really supporting the pact and its broad purpose.

"Solidarity, responsibility, sharing proper mechanisms for rescue at sea, proper monitoring, proper reception facilities, but done in a way that's genuinely an EU solidarity exercise consistent with the compact on refugees. We think that it's a basis for negotiations. Of course it's not yet final, but we think that the challenge is to find that consensus and we think that the mechanisms are in the pact, which can lead to building that consensus. We're certainly optimistic."

The future, for thousands of refugees in Europe, remains uncertain - a despairing feeling COVID-19 is getting us all a sense of.

简体中文

简体中文