Congressional Republicans have intensified their attacks on President Biden’s spending, raised fresh concerns about the growing federal deficit and floated the specter of a fight this summer over the debt ceiling.

Four years after racking up big bills under President Donald Trump, the party’s strategy is becoming clear: Republicans are straining to revive their message of fiscal discipline now that Democrats are in charge.

The renewed Republican commitment to austerity marks a shift for a party that had lined up to advance Trump’s policies to build a border wall and expand the U.S. military with few objections, even as Congress added trillions of dollars to the deficit in the process. And it threatens to complicate the future of Biden’s economic agenda, including his proposed $2 trillion in upgrades to the nation’s aging infrastructure — and a plan to be unveiled this week that dedicates $1.8 trillion to families and child care.

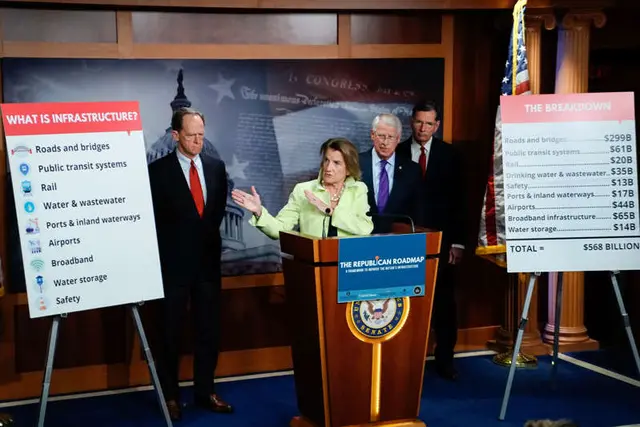

The tensions were on display Thursday, as Senate Republicans unveiled a $568 billion infrastructure counteroffer that amounts to about a quarter of what Biden had proposed. In keeping with GOP orthodoxy, party lawmakers also excluded any tax increases to pay for the package, offering few specifics about their alternative idea — to rely on unspecified user fees and unused stimulus money — to cover the cost.

The vague details suggested divisions within the GOP about the size and scope of the package. But Republican observers said the approach reflected a shrewd political calculation. Judd Gregg, a former Republican senator from New Hampshire, said the proposal would be “dead on arrival” if GOP lawmakers had offered more specificity about the ways they intend to finance infrastructure reforms.

“I’ll be surprised if they reach an agreement,” he said. “I just think they’re philosophically a long way apart.”

The battle this week marks a retreat to familiar territory in ever-divided Washington, which has spent much of the past year taking drastic steps in response to the coronavirus pandemic. With the economy in shambles, the two parties united to authorize trillions of dollars in emergency aid — and now that it is on the mend they’re increasingly divided over the future of the federal ledger.

“We’re going to come out of emergency mode,” said Garrett Watson, a senior policy analyst at the Tax Foundation, predicting a return to fights over the deficit.

Democrats newly in charge of the White House and Congress have grown more aggressive in their embrace of the idea that big government spending can help address the country’s most pervasive economic ills. Since taking office, Biden has helped authorize $1.9 trillion in additional long-term stimulus aid and put forward a budget that includes massive investments in education and health in 2022. His forthcoming American Families Plan calls for an additional $1 trillion in support for paid leave, child care and prekindergarten, seeking to raise the money through higher taxes on the wealthiest earners.

Republicans, however, increasingly have sounded alarms about the growing federal deficit and the potential that heightened government spending could inflate prices. The Senate GOP voted unanimously against the most recent coronavirus stimulus package, known as the American Jobs Plan, and many sharply criticized Biden’s 2022 budget over its proposed increases, saying the spending is wasteful or unnecessary.

The pivot back to restraint comes even though the federal debt swelled under Trump by about $7 trillion, driven in no small part by the tax cuts for wealthy earners and highly profitable corporations that the president and his Republican allies secured in 2017. Trump rarely talked about the deficit as president, allowing it to grow each year under his watch until it breached $3.1 trillion in 2020. It is expected to stay elevated as spending far outpaces tax revenue.

Republicans are now trying to return to the fiscal restraint they called for before Trump’s presidency. Ahead of the president’s speech to Congress, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) attacked Biden’s broader economic agenda, saying on the Senate floor that the president had assembled “a patchwork of left-wing social engineering programs” and then wrongly sought “to label it infrastructure.”

The heated rhetoric threatens to become a more dramatic standoff as soon as this summer.

In an early, ominous sign, Senate Republicans on Wednesday fired a warning shot over the debt ceiling, the amount of money the U.S. government can borrow to cover its financial obligations. Congress suspended the ceiling through July, at which point lawmakers must vote to suspend it again or raise it — or risk a potentially devastating default.

Republicans, however, said they may not vote to approve that unless Democrats couple it with spending cuts or other structural reforms. Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas told reporters that it amounted to a “step in the right direction in terms of reining in out-of-control spending.”

The Senate GOP adopted the position as part of its party rules, meaning it is more aspirational than binding. But its inclusion is a reminder of 2011, when Republicans resisted then-President Barack Obama over a debt ceiling increase — and nearly brought the country to default — before ultimately securing a decade of caps on federal spending that only now are expiring.

For its part, the White House this week signaled a cool reception to any negotiation on the debt ceiling. An official emphasized in a statement that the Biden administration expected congressional lawmakers to do much as they had “three times during the Trump administration and amend the debt limit law as needed.”

Still, Senate veterans say they do not expect the Capitol to be enveloped by another debt crisis, the likes of which previously had spooked global markets and poisoned political relations between the two parties. Instead, they called the threat symbolic on the part of spending-wary Republicans as other economic debates get underway.

“I’d be a little bit surprised [about a debt ceiling showdown] because I think at the end of the day everyone understands default is not really an option,” said Rohit Kumar, a former senior aide to McConnell who now is a senior executive at PwC’s tax practice. “It’s a continued expression of concern about all of the spending that they think perhaps is poorly targeted. … This is just another way to express that point of view.”

Republican lawmakers ratcheted up the spending criticisms on Thursday, as Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (W.Va.) and others joined to unveil their own infrastructure reform blueprint. The $568 billion package puts most of its money toward road, bridge and highway repairs, with additional sums set aside to replace pipes, improve airports and sea ports and build out broadband connectivity nationwide.

The GOP positioned its plan as a more frugal alternative to Biden’s proposal, which they faulted for devoting some of its total $2 trillion in spending to issues such as combating climate change and upgrading schools.

Quickly, though, questions emerged about how much of the GOP plan contained new spending — or if it is built on existing or recently proposed appropriations. Its price tag nonetheless marked a break with Trump, who had endorsed $2 trillion in infrastructure spending as part of a broader, jobs-focused response in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic.

Republicans enshrined their ideas in a two-page document, which also offered few details about how it would be funded. GOP lawmakers generally said they hope to finance their infrastructure reforms through fees imposed on the users of infrastructure. That could include, for example, the drivers of electric vehicles, who do not currently pay gas taxes that fund highway development. But the GOP blueprint included no numbers, and it didn’t spell out any of the other fees that might fund the federal fixes.

The lack of specificity troubled tax experts, who said it was difficult to evaluate whether the plan could be paid for in this manner. Republicans also said they could finance infrastructure repairs through repurposing federal stimulus dollars but didn’t identify what they would recapture for reuse. Capito later told reporters that they could identify unused funds by 2024 for the purpose of paying for future infrastructure legislation.

As negotiations began in earnest, Democrats criticized the GOP proposal. Sen. Ron Wyden (Ore.) blasted it as too small, “not good enough” and wrongly financed through fees that would leave families to “pick up the tab for the investments.”

Senate Republicans, however, emphasized that it reflected a broader view among their conference that they needed to be more judicious about opening the federal purse.

“We need to cover the cost of infrastructure bills to avoid increasing the debt,” Capito said, noting that it is still the “largest infrastructure investment” Republicans have ever put forward.

(THE WASHINGTON POST)

简体中文

简体中文