A weather event in the Indian Ocean, known for triggering catastrophic bushfires in Australia and breeding crop-gorging locust swarms in Africa, also played a pivotal role in ravaging floods in China last year, according to a study on Tuesday.

The unusually strong Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and a weak El Niño in the Pacific Ocean contributed to unexpected heavy summer rainfall – known as the mei-yu – along the Yangtze River belt in China, affecting one-third of the country's population residing in the region.

Last year's rainfalls, the heaviest since 1961, killed 128 people, flattened 28,000 homes, leading to a financial loss of more than $11 billion at the peak of the coronavirus pandemic, hampering efforts to prevent the transmission of the deadly virus in the country.

The same weather event destroyed 18 million acres of forests in bushfires in Australia, decimating the country's biodiversity and pushed animals like koalas to the brink of extinction. It also led to flooding in African countries and provided a favorable humid condition for locusts to breed. These swarms destroyed hundreds of acres of standing crops in food-insecure countries in Africa and Asia.

While IOD's role in triggering a bushfire in Australia and heavy rainfall in Africa has been well documented, its capability to start a heavy downpour in China was little known. The unusual weather along the Yangtze River also left meteorologists stunned.

The IOD in 2019, which was one of the strongest on the records, led to atmospheric changes over six months, bringing heavy downpour in China in 2020, said a

study

by Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Fudan University researchers published in the journal PNAS.

"The results of our study surprised us," said Shang-Ping Xie, a professor of climate science at Scripps Oceanography.

"Actually, researchers stopped paying attention to IOD's impact in the region about 20 years ago. The last time such a strong event happened was in 1997," Xie told CGTN.

Disaster brewing between two poles of the Indian Ocean

The two ends of the dipole in the Indian Ocean are located along the equator, one on the western side, near Africa, and the other on the eastern side, close to Indonesia. Each side has either cold or hot water, which causes a range of weather events in Australia, Africa and Asia. Winds and seawater movement from the Pacific Ocean makes the atmospheric disturbances more pronounced.

In 2019, the western side of the basin, toward the east African coast, was unusually warm. The topmost layer of warm surface water was 70 meters thicker than normal. On the eastern side, around Indonesia, sea surface temperature was unusually cold.

Two extremes like that set up what is called a dipole in ocean temperature. The weather difference between the two poles stokes winds in the way winds kick up anywhere where high- and low-pressure weather systems interact, researchers explained.

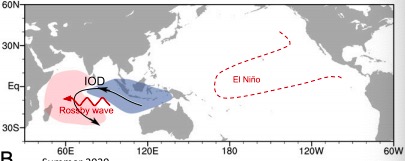

The Indian Ocean Dipole and El Niño in the Pacific Ocean caused a devastating weather pattern in Australia, Africa and China. /Grap

"An exceptionally warm sea near Africa resulted in cloud formation over the region bringing heavy rains but left Australia dry. But on Southeast Asia side, the impact was seen a few months later, with unexpected heavy rainfalls in China," said Zhen-Qiang Zhou, lead author of the study.

The study identifies a recurring regional pattern triggered by the Indian Ocean warming which causes distinct atmospheric circulation patterns to intensify monsoon rains over East Asia. The study establishes a regional pattern, which could be triggered by El Niño via Rossby waves in the Indian Ocean.

Accurate weather forecast to prevent disasters

But for the weather forecasters and policymakers, the formation of IOD and its inclusion in early warning systems have remained low on their priority. They focus more on Al Nino and El Nina's development in the Pacific Ocean to track clouds and rainfall over East Asia.

"Mainstream forecasting has traditionally focused on what is happening in the Pacific Ocean when deciding if winter seasons will be El Niños, La Niñas, or somewhere in between," researchers said.

The most commonly used predictor of El Niño or La Niña years is the location of a pool of warm water along the equatorial Pacific, which tends to move in a pendulum fashion between the western and eastern boundaries of the basin, they added.

The new findings could help enhance weather forecast and early warning systems to provide ample time for evacuations before the flooding. "We would strongly recommend weather agencies to keep a vigil on IOD and use computer modeling for forecasting rainfall in the region," said Xie.

"We should put more trust in those computer models over empirical predictions."

(Cover: Rescue workers evacuate with an inflatable boat students stranded by floodwaters at a school, amid heavy rainfall in Duchang county, Jiangxi province, China July 8, 2020. /Reuters)

简体中文

简体中文