The Earth's magnetic field can change 10 times faster than previously thought, according to a new study.

Researchers at universities in the UK and the US have provided new insights into how the swirling molten iron 1,740 miles (2,800km) below the Earth's surface influences the planet's magnetic field.

Their work found a sharp change in the geomagnetic field direction of roughly 2.5 degrees per year 39,000 years ago - far faster than was previously believed possible.

A maritime mystery: What has been causing ships to sail in circles?

The molten metal at the Earth's core creates powerful electric currents that generate our planet's magnetic field. All life on the planet depends on this as protection from harmful solar radiation.

In the clearest example analysed by the researchers, the shift was associated with a locally weakened magnetic field just off of the west coast of Central America, which occurred shortly something called the Laschamp event, a short rapid reversal of the Earth's magnetic field.

During the Laschamp event, the reduction in the strength of the Earth's magnetic field meant the planet was bombarded with more cosmic rays than usual - causing a huge peak in radioactive elements which can be observed in ice cores dated to this period.

Although modern-day measurements of the field can be conducted with satellites, scientists' knowledge of how it worked over a longer timescale has been extremely limited until now.

Understanding these things is a pressing matter. The planet's magnetic field has lost almost 10% of its strength in average over the last two centuries, and there is currently a large localised region of weakness stretching from Africa to South America.

Known as the

South Atlantic Anomaly

, the field strength in this area has rapidly shrunk over the past 50 years just as the area itself has grown and moved westward.

Now, Dr Chris Davies, associate professor at the University of Leeds, and Professor Catherine Constable from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, have taken a new approach to analysing what these changes mean for Earth's most vital protection.

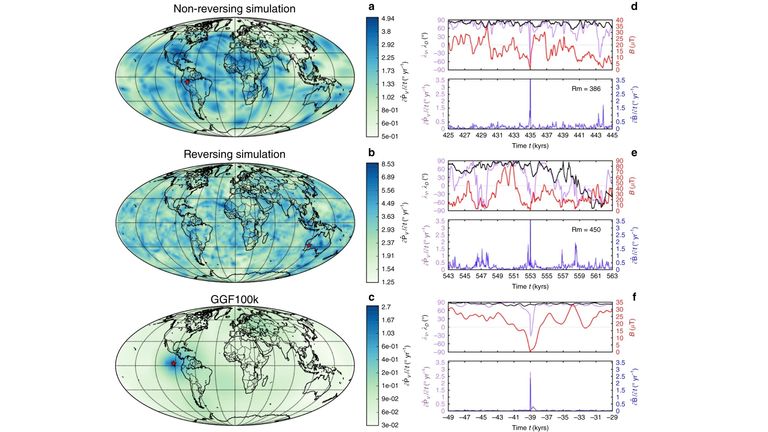

The researchers conducted computer simulations of how the Earth's magnetic field is generated, combined with a recently published reconstruction of how the magnetic field has varied over the last 100,000 years, and found it could change rapidly.

They found that the direction of the magnetic field could move 10 times faster than what scientists currently believe is the maximum, and demonstrated how these changes are associated with local weakening of the field - such as in the South Atlantic Anomaly.

Image:The magnetic field could change rapidly. Pic: Nature

Dr Davies told Sky News that his historical survey found that rapid changes to the magnetic field's movement typically occurred in areas where the field was unusually weak.

He said: "We have very incomplete knowledge of our magnetic field prior to 400 years ago.

"Since these rapid changes represent some of the more extreme behaviour of the liquid core they could give important information about the behaviour of Earth's deep interior," Dr Davies added.

Professor Constable said: "Understanding whether computer simulations of the magnetic field accurately reflect the physical behaviour of the geomagnetic field as inferred from geological records can be very challenging.

"But in this case we have been able to show excellent agreement in both the rates of change and general location of the most extreme events across a range of computer simulations.

"Further study of the evolving dynamics in these simulations offers a useful strategy for documenting how such rapid changes occur and whether they are also found during times of stable magnetic polarity like what we are experiencing today."

简体中文

简体中文