Chimpanzees smack their lips in a rhythm similar to human speech - which could solve the mystery of how speech evolved, a new study has found.

It was already known that monkeys use the fast-paced cycles of vertical jaw movement to communicate with each other.

But scientists, for the first time, observed these mouth signals in great apes and found they smack their lips at the same pace as humans speaking.

They believe their findings, published in the journal Biology Letters, could be a "critical step" towards unlocking the mystery of how speech evolved in humans.

Humans are thought to open their mouths between two and seven times per second while talking, with each open-close cycle corresponding to a syllable.

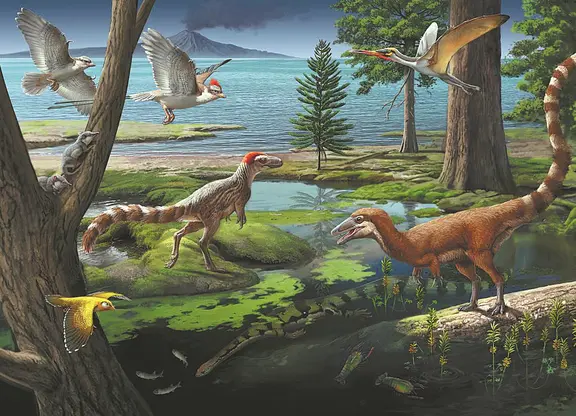

This speech-like rhythm has been observed in other monkey species including gibbons, orangutans and macaques.

However, the lip smacks of the closest species to humans - the African great ape - had never been studied, the scientists said.

The team of researchers, including scientists from the University of St Andrews, the University of York and the University of Warwick, looked at data from four chimpanzee populations.

They analysed video recordings of the primates from Edinburgh Zoo and Leipzig Zoo in Germany, as well as from wild apes in Uganda's Kanyawara and the Wibira.

Chimps filmed smashing open tortoise shells

The chimps made lip smacks while grooming another, opening and closing their mouths an average of four times per second.

According to the experts, these findings confirm human speech has "ancient roots within primate communication".

They believe the mouth signals may have played a role in the evolution of a vocal system in humans that laid the foundation for speech.

Study author Dr Adriano Lameira, from the department of psychology at the University of Warwick, said: "Our results prove that spoken language was pulled together within our ancestral lineage using 'ingredients' that were already available and in use by other primates and hominids.

"This dispels much of the scientific enigma that language evolution has represented so far."

He said the team found "pronounced differences" in rhythm between different chimpanzee populations which suggest they are "not the automatic and sterotypical signals so often attributed to our ape cousins".

"Instead, just like in humans, we should start seriously considering that individual differences, social conventions and environmental factors may play a role in how chimpanzees engage 'in conversation' with one another," he added.

简体中文

简体中文