Editor's note: Ji Xianbai, PhD, is a research fellow with the International Political Economy Program of S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. He is also an associate fellow of the EU Centre in Singapore. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

When U.S. President Donald Trump began his purge on America's trade with China in early 2018, the United States was China's second largest merchandise trading partner after the European Union (EU).

Two years on, the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has taken over as China's second largest trading partner in goods.

In 2019, China's trade volume with ASEAN climbed by 14 percent to 4.43 trillion yuan. The EU remained China's single largest trading partner with 4.86 trillion yuan in bilateral trade and an eight percent year-on-year growth rate (the U.S. has relegated to the third place on the list of China's top trading partners with bilateral trade contracting more than 10 percent to around 3.73 trillion yuan).

Taking into account Brexit (Britain accounts for around 10 percent of the EU's trade with China), the respective growth trajectories of China-EU and China-ASEAN commercial relations in the past few years, the seriousness of the economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic on the virus-stricken European economy, and relocation of some manufacturing capabilities from China to neighboring Southeast Asian countries amid the U.S.-China trade conflicts, it is reasonably conceivable that ASEAN would surpass the EU as China's largest trading partner in 2021 – if not this year.

Whereas China-Europe trading relationship is one of producer-consumer (trading finished products for consumption), China's trade pattern with ASEAN is underpinned by a production fragmentation partnership characterized by components passing from economy to economy before being manufactured, normally in China, into a final tradeable product.

In fact, the whole of East Asia has been organized into layers of cross-border supply chains and regional production sharing networks by multinational corporations and governments' pro-trade public policies.

This China-ASEAN co-production relationship has been reflected in the trade statistics. In 2018, the most traded goods between China and ASEAN were machinery and mechanical appliances, minerals, chemicals and plastics, and iron and steel.

Such sectors are also those which have seen most robust growth in the past fifteen years or so. Between 2004 and 2018, in contrast, China-ASEAN trade in non-ferrous metals such as zinc and lead, art works, silk and photographic/cinematographic goods were on the decline.

To uplift China-ASEAN trade to the next level, two policy recommendations could be considered by regional governments.

First, countries should continue to individually uphold outward-looking and external-oriented economic policies while collaborating to provide joint policy support to interconnected economic growth.

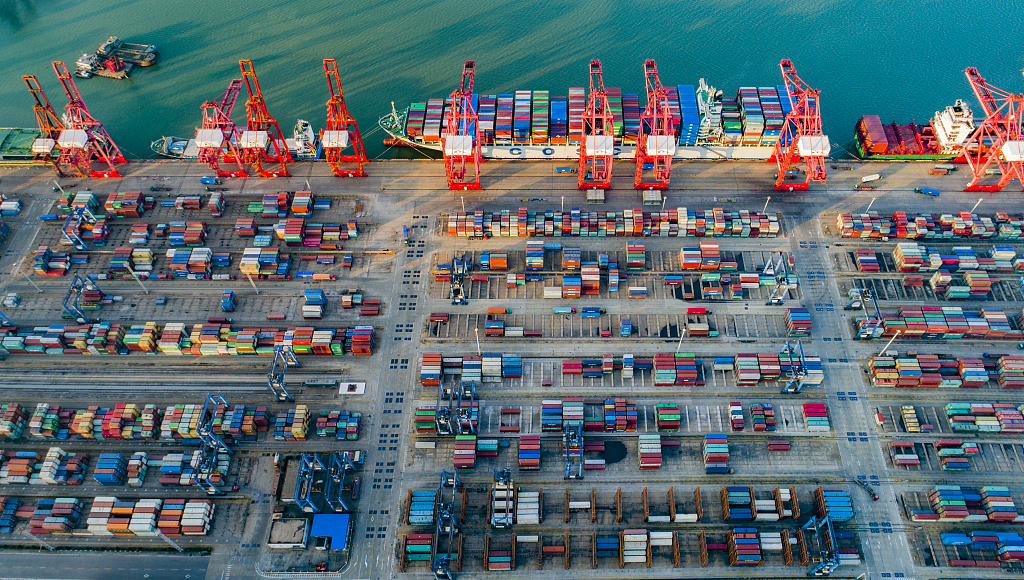

A port in Jiangsu Province, China, January 9, 2018. /VCG

Malaysia, despite the recent political turmoil, and Brunei should ratify the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership as soon as possible to unleash their growth potentials and to address regulatory barriers to economic efficiency and welfare improvement.

East Asian countries should also get the negotiations for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) over the line this year.

India's participation in RCEP is most welcome but the overall negotiation and integration progress should not be held hostage by India or any other countries for that matter.

Second, it is needed to identify new growth engines to propel already strong China-ASEAN economic relations forward. An ideal area of cooperation is the digital economy.

Under the policy support of the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese internet conglomerates including the so-called BATJ (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and JD.com) have all stepped up commercial presence and tech investments into Southeast Asia.

JD.com is a particularly interesting case given the current COVID-19 outbreak. Established as a traditional off-line IT products retailer, the company was literally on the brink of bankruptcy because of SARS-induced demand nosedive in 2003.

The management then adopted an online business model in 2004, successfully turning the company around. Now JD.com is investing in Southeast Asia's e-commerce and logistics networks especially in Indonesia.

Its unique business transformation experience will prove inspirational for ASEAN countries looking to digital economy for jumpstarting a new round of economic takeoff.

As China-ASEAN commercial ties grow from strength to strength, what can be called "China-ASEAN Community of Shared Future for Trade" with one having a stake in the economic prosperity of the other is firmly taking hold.

In that sense perhaps, we should thank Trump's "decoupling" protectionism which has only worked to advance China-led economic cooperation and integration in Asia Pacific.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at [email protected].)

简体中文

简体中文